According to the United Nations report, around 800 million people, or 10 percent of the world's population, were anticipated to suffer from hunger in 2021, while 2.3 billion people, or 30 percent of the world's population, were predicted to face moderate or severe food insecurity. A nutrient-rich diet was beyond reach for almost 3 billion people in 2020, an increase of 100 million from 2019.

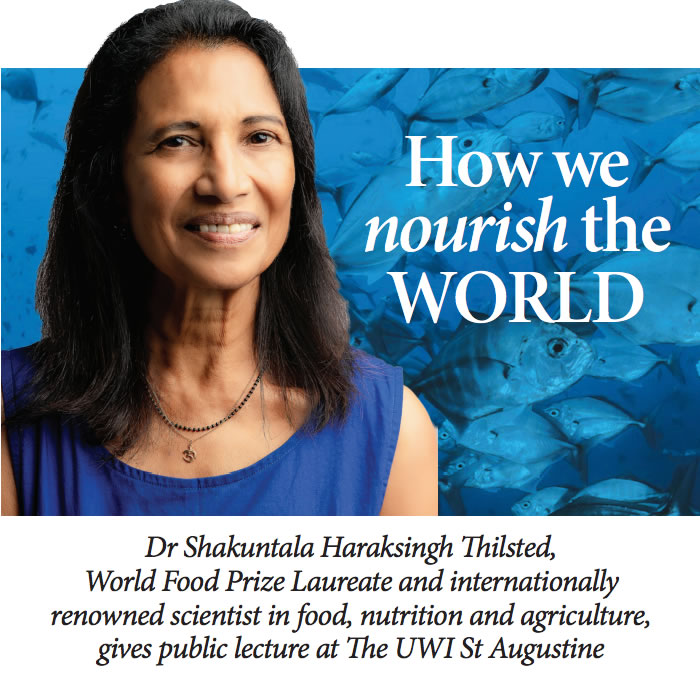

Dr Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted knows quite a bit about hunger and malnutrition and how to address it. She is the World Food Prize Laureate and also received the prestigious Arrell Global Food Innovation Award in 2021, for her ground-breaking work on fish-based food systems to combat malnutrition, and sustain children and women in underdeveloped regions in Asia, Africa and the Pacific. Since 2020, she has been the Global Lead for Nutrition and Public Health at the CGIAR research centre, WorldFish, with headquarters in Penang, Malaysia.

This October, she returned to The UWI St Augustine, where she attained her undergraduate degree at the Faculty of Agriculture, to both receive an honorary doctorate from the university and speak on this crucial topic.

“Transforming Food Systems: Building Resilience, Nourishing People and Improving Livelihoods with Aquatic Foods”, a UWI Open Lecture, was held on October 26 at the Daaga Auditorium of The UWI St Augustine campus. In her presentation, Dr Haraksingh Thilsted shared that world hunger and malnutrition would continue to effect populations for years to come.

It is now projected, she explained, that approximately 670 million people will continue to face hunger in 2030. Conflicts such as the war in Ukraine, climate change and COVID-19 have decelerated the substantial progress that has been made in fighting hunger and malnutrition globally.

In our region, there is a scarcity of data on malnutrition. “There is much work to be done in this area, in order to monitor progress with the changes we hope to implement,” she said. Dr Haraksingh Thilsted also focused on solutions to global hunger and malnutrition, what is being done and what can be done in the future.

“Many global efforts have been made to achieve food and nutrition security,” she told the audience.

These efforts included initiatives such as the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 where Caribbean nations pledged to achieve various goals. For example, Barbados pledged to reduce their food import bill, while Guyana pledged to promote greater food and nutrition security by investing in research and development, diversifying agricultural production, and boosting agro-processing, while investing in agricultural-support infrastructure.

Guyana’s pledges were similar to the plans presented in Trinidad and Tobago’s Budget Statement 2023. Dr Haraksingh Thilsted spoke favourably of the government’s approach.

To solve global food and nutrition insecurity, Dr Haraksingh Thilsted advocates, “We must distance ourselves from the narrative of ‘feeding our population’, which could encourage a reliance on a few staple foods, to ‘nourishing all people and our planet’, which considers diverse food groups, nutritional value, food safety, reducing food loss and waste and environmental concerns.”

Her work focuses on aquatic foods as a way to address food and nutrition insecurity, poor growth and development in children, obesity, and high rates of poverty. Aquatic foods, she said, include “animals, plants and microorganisms that are farmed in and harvested from water, as well as cell- and plant-based foods emerging from new technologies”. They are obtained from diverse aquatic environments, oceans and inland waters.

Currently, 3.3 billion people consume aquatic foods, and 800 million depend on aquatic food systems for livelihoods and income. These systems are also vital for sustainable development as they “have the potential to contribute holistically to all three pillars [social, economic, and environmental] of sustainable development”, she explained.

Dr Haraksingh Thilsted also said aquatic foods contribute to several of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – No Poverty, Zero Hunger, Good Health and Well Being, Gender Equality, Decent Work and Economic Growth, Climate Action, and Life Below Water.

In addition, the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly referred to as COP27, will include the themes of food and nutrition security and transformation of food systems. They were first linked to climate change last year at COP26.

In 2021, UN Nutrition, in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and WorldFish, published a paper highlighting aquatic foods' capability to transform global food and nutrition security, Dr Haraksingh Thilsted said.

She pointed to several ways to increase the consumption of aquatic foods:

Moving to a diet rich with diverse aquatic foods requires more food production – sustainable food production. Dr Haraksingh Thilsted pointed towards the polyculture practices of countries in Asia and some in Africa. Fish farmers cultivate multiple species in homestead ponds and integrated aquatic/terrestrial production systems.

In parts of India, village ponds and even water tanks have been used to produce fish. In such places, the contribution of women as part of the production system was an unexpected societal benefit. Their work has historically been undervalued, unpaid and even prohibited.

Dr Haraksingh Thilsted said that it was important to build partnerships with institutions such as universities and intergovernmental organisations like CARICOM, as well as to influence policymakers to include nutrition-sensitive aquatic food systems in their plans and research investments.

For these systems to be sustainable far into the future, she explained, youth engagement must be strongly considered, as most aquatic food system workers are of the older generations.

In Dr Haraksingh Thilsted's view, the starting point to changing the perception of healthy diets is connecting to the youth through nutrition messaging and social behaviour change. Once more young people consider not just what they wish to eat, but what they should eat and which options are most sustainable, then slowly, the perception of healthy diets would become more attractive.

A change in this direction would amplify the demand for diverse healthy and nutritious foods, creating a chain reaction through the food system, also with food providers, and leading to a well-nourished population who can contribute to national development.