|

|

|

|

February 2014

|

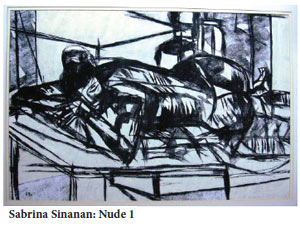

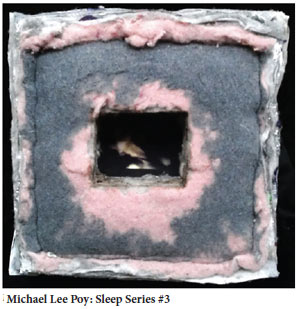

This is the second exhibition organized this semester. The first exhibition in October, “Visual Interpretations of Body/Institution/Memory” was a contribution to the symposium Caribbean Intransit. In that first event, the DCFA curated the work of eight alumni who are raising questions about the body in a variety of media, techniques and materials. The exhibition, despite disrupting our teaching studios, did not attract much of an audience. As a consequence, this second exhibition at the ASTT Gallery in its seventieth anniversary year was an opportunity not to be missed. Visual artists need a place to see and be seen by a critical audience. The exhibition “Interpretations of the Human Figure” of December 2013 has its origins in the earlier excitement the DCFA 25th Anniversary Exhibition of December 2012. At that time, the curatorial committee committed to hosting annual themed exhibitions, which were envisaged as promotional platforms for the artwork of alumni, students and staff. As a consequence, this first themed exhibition “Interpretations of the Human Figure” sought to focus on the human figure, its form, the physicality of its presence, its compulsions. It was themed ambitiously, to explore the nature of being and function of the figure as a form in art. The human figure is the paradigmatic subject/object for representing human concerns. Its depiction is both means and end in a process for drawing out social concerns about identity, intimacy, as well as for tapping into the collective unconscious of individuals and groups. The artistic purpose of depicting the figure is rooted in the technical, material-based cultures, rooted in systems of observing and providing insight to the problems of Theory apart, the “Interpretations of the Human Figure” exhibition comprised over 60 items made of acrylic, oil and watercolour paints, graphite, charcoal, pastels, conte crayon, encaustic, ink, plexiglass and mixed media; with some items created with photographic processes, digital media and electronic printing on polyvinyl. Most of the exhibits were two-dimensional drawings, except that Michael Lee Poy offered four shadow boxes comprising photographs in a bas-relief. Aisha Provoteaux offered a free-standing, life-size figure paper sculpture. Marisa Ramdeen showed a quarter scale clay head, and Roger McCollin installed his electronic system invented for digital construction of the figure. The facts of number and range of material, however, do not fully explain the scale of the exhibition. The ASTT Gallery, in its space-saving layout of walls, offers views of no more than 20 feet between the entrance and back wall. As a consequence, the ‘architecture’ and layout of the small, white room participates very prominently in exhibitions. In this instance, the space anchors the exchanges between the artists and the audience in an intimate visual dialogue. Of course, nothing diminishes the power of direct observation, and the short distances between artworks unmask several challenges of interpretation. It is precisely because of the variable ways in which the figures and space can be interpreted that much can be seen in this exhibition.

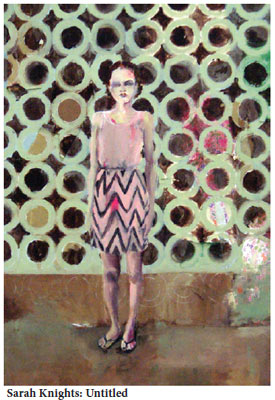

The transition into the second space is abrupt. The life-sized figure sculpture by Aisha Provoteaux evokes a feeling of naturalness. It is a self-portrait, but conveys a physicality and an apprehension of space that is hard to describe. It is a shocking work that, in context with Sarah Knights’ large paintings, aspires to be real and true and honest depictions of the female figure. The sculpture and the paintings set out an attitude and presence that explore inner reality as the dominant concern of the exhibition. Accordingly, this second space emerges as an arena for competing representations, in which the viewer can observe the contest for the representation of the female figure. It presents the drawings of Rajendra Ramkelawan, Kern Pierre, Richard Rampersad, Ian Thompson, Naje Hart, Luke Lashley—young men who have chosen to pose their female figures as svelte shapes; elegant, with polished textures and even temperaments. Their drawings are of ‘babes,’ tactile, potentially fertile, available, constructs of seductive curves and secret crevices, figments for adoration that undulate into the visual pleasure and consumption of fantasy.

This second space is an arena for cultural debate about the politics of gender and representation. It is a provocative space. The interpretations of the figures have undertones that demonstrate the great divide between idealism and realism. The human figure is what it is, and in these interpretations the viewer discovers that acceptance of one’s identity is an elemental dynamic of our humanity. The third space is loud, full of opinion, challenging media and aesthetic controversy. Among the standouts here is Alex Kelly’s “Apple a day,” an enigmatically grotesque figure ‘eating’ the apple icon. It is shown with Shalini Singh’s “Cameo: David” a profile, she romanticizes in a detail of Michelangelo’s famous sculpture. In the tumult of the installation, Shalini’s optimistic view juxtaposed to Alex’s darkly ironic portrait, excavates the ‘connected’ world. They present the collision of ideas as potent forces that are discussed only sporadically in the cosseted, entertained and ‘friended’ cyber-world. According to Alex Kelly, we are tragically unaware of the poisoned apple that makes the world vulnerable to disruption as we are never more than a hair’s breadth from. The “Apple” we eat today will not keep the doctor away and save the world from the monstrous spectre of machine domination.

Perhaps more than any other visual art, the public exhibition of concerns about the human figure is handicapped by lack of opportunities. Drawings of the human figure in particular are limited to student exhibitions. They are rarely collected and worse, are typically thought of as preliminary work. As this review has hopefully demonstrated, themed exhibitions have much to offer the evolution of thought and process in the visual arts of this 21st century. Kenwyn Crichlow is an artist and a lecturer at the Department of Festival and Creative Arts, The UWI, St Augustine. |

The intention of this paper is to comment on the “Interpretations of the Human Figure” exhibition, a recent outreach project of the Visual Arts Unit of the DCFA at The UWI.

The intention of this paper is to comment on the “Interpretations of the Human Figure” exhibition, a recent outreach project of the Visual Arts Unit of the DCFA at The UWI.  proportion, scale and the function of material form in art.

proportion, scale and the function of material form in art. The exhibition is installed in three open-plan units, each a viewing space flowing into the next, each bringing to focus the interpretations that dominate the exhibition. The first space is heralded by the large, brooding silhouettes by Camille Harding and Michelle Isava. The figures are troubled, potentially violent figures. Each is male and posed, standing in shallow, indeterminate pictorial spaces, isolated. There is an ambiguous disquiet among these figures. They are in states of psychological crises and fill the gallery with an un-nerving presence. These dark drawings stand in stark contrast to those by Kamillah Jackson, Marisa Ramdeen and Darron Small, whose interpretations are a delight of technical prowess. Kamillah Jackson, for example conveys her ideas about the sleeping figure in foreshortened poses, a technical challenge she meets with dexterity and close observation. Marisa Ramdeen’s self-portraits are traditional compositions, but to avoid sentimental vanity are written upon and embedded with words of personal significance.

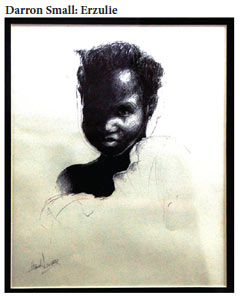

The exhibition is installed in three open-plan units, each a viewing space flowing into the next, each bringing to focus the interpretations that dominate the exhibition. The first space is heralded by the large, brooding silhouettes by Camille Harding and Michelle Isava. The figures are troubled, potentially violent figures. Each is male and posed, standing in shallow, indeterminate pictorial spaces, isolated. There is an ambiguous disquiet among these figures. They are in states of psychological crises and fill the gallery with an un-nerving presence. These dark drawings stand in stark contrast to those by Kamillah Jackson, Marisa Ramdeen and Darron Small, whose interpretations are a delight of technical prowess. Kamillah Jackson, for example conveys her ideas about the sleeping figure in foreshortened poses, a technical challenge she meets with dexterity and close observation. Marisa Ramdeen’s self-portraits are traditional compositions, but to avoid sentimental vanity are written upon and embedded with words of personal significance.  The drawings in this space are for intellectual delectation, neat, finely crafted and purposeful. In this regard Darron Small displays an uncommon grasp of the function of light and shade in the uses of various drawing media. Generally, light and shade techniques dominate the exhibition. Light is applied as a tool for highlighting the tone and mood of the figures. Shade is for constructing the volume and character of form. Darron’s use of the biro, drawing pen and mixed media is so wonderfully light-handed that drawing is for him a way of nuancing eye-catching characterizations. His drawings are portraits of visual pleasure and are distinct from Elsa Carrington-Clarke’s six line drawings. Elsa’s drawings are amusing, nonchalant. Her use of line rising and falling between gesture and contour is a feat of hand-and-eye coordination that offers a way of seeing the figure as from a ‘corner’ of the eye.

The drawings in this space are for intellectual delectation, neat, finely crafted and purposeful. In this regard Darron Small displays an uncommon grasp of the function of light and shade in the uses of various drawing media. Generally, light and shade techniques dominate the exhibition. Light is applied as a tool for highlighting the tone and mood of the figures. Shade is for constructing the volume and character of form. Darron’s use of the biro, drawing pen and mixed media is so wonderfully light-handed that drawing is for him a way of nuancing eye-catching characterizations. His drawings are portraits of visual pleasure and are distinct from Elsa Carrington-Clarke’s six line drawings. Elsa’s drawings are amusing, nonchalant. Her use of line rising and falling between gesture and contour is a feat of hand-and-eye coordination that offers a way of seeing the figure as from a ‘corner’ of the eye.  The interpretations of the men collide with those of Aisha and Sarah; setting off a contest between perception and reality. The men circle notions of visual pleasure and sensual fantasy. The women are concerned with interpretations of female reality, which they offer as reflections on personal experience. Aisha offers a realistic depiction of a woman much like herself, a figure that has borne children and bears the marks of her living. Sarah’s figures have a sense of anxiety and inner turmoil that is both acute and multifaceted. Her figures assume amazingly fluid poses; each interpretation looks completely different from one moment to the next. Together, Aisha and Sarah create narratives of deep and delicate emotion. Yet, as fragile and fearful and striving as these are, their interpretations convey very real notions of our humanity.

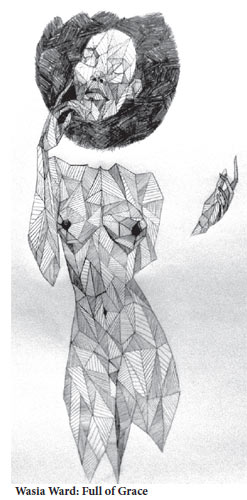

The interpretations of the men collide with those of Aisha and Sarah; setting off a contest between perception and reality. The men circle notions of visual pleasure and sensual fantasy. The women are concerned with interpretations of female reality, which they offer as reflections on personal experience. Aisha offers a realistic depiction of a woman much like herself, a figure that has borne children and bears the marks of her living. Sarah’s figures have a sense of anxiety and inner turmoil that is both acute and multifaceted. Her figures assume amazingly fluid poses; each interpretation looks completely different from one moment to the next. Together, Aisha and Sarah create narratives of deep and delicate emotion. Yet, as fragile and fearful and striving as these are, their interpretations convey very real notions of our humanity.  Roger McCollins’ electronic installation is a machine; it uses the ‘smart technologies’ of touch on an electronic interface to show a way the female figure may be constructed. His application of interactive media offers the viewer opportunities “to draw your own figure” in the style of glossy pop-culture magazines. Roger’s invention raises questions about the status of the hand-made artifact and the use of new digital media and technologies to make interpretations. Similarly, Michael Lee Poy’s shadow boxes are finely crafted items made of local woods and glass. But they are peepholes, which he traps under glass in an amusing satire about a pattern of consumption by the “media porn industry” of female bodies as erotic material. The other standout in this space is the collaboration between Gerrel Saunders and Wasia Ward, they have offered a figure constructed of symbols derived from Mehndi drawings as a print on polyvinyl.

Roger McCollins’ electronic installation is a machine; it uses the ‘smart technologies’ of touch on an electronic interface to show a way the female figure may be constructed. His application of interactive media offers the viewer opportunities “to draw your own figure” in the style of glossy pop-culture magazines. Roger’s invention raises questions about the status of the hand-made artifact and the use of new digital media and technologies to make interpretations. Similarly, Michael Lee Poy’s shadow boxes are finely crafted items made of local woods and glass. But they are peepholes, which he traps under glass in an amusing satire about a pattern of consumption by the “media porn industry” of female bodies as erotic material. The other standout in this space is the collaboration between Gerrel Saunders and Wasia Ward, they have offered a figure constructed of symbols derived from Mehndi drawings as a print on polyvinyl.