|

|

|

|

February 2016

|

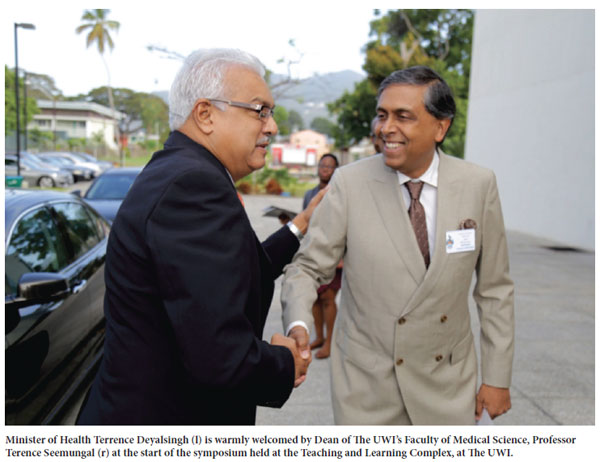

Minister of Health, Terrence Deyalsingh brought remarks and Dr Rakhee Palekar, Feature Speaker, presented on the ‘Epidemiology of H1N1 Infections’. Dr Palekar is Palekar is a medical epidemiologist on the influenza team of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Also speaking were Dr Clive Tilluckdharry, Chief Medical Officer, Ministry of Health and the Dean of The UWI’s Faculty of Medical Science, Professor Terence Seemungal. Professor Seemungal led a slate of UWI experts and medical practitioners who addressed the clinical aspects of the H1N1 and Zika diseases and facilitated a panel discussion on the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and control of the viruses, mapping the way forward. “The Zika virus (ZIKV) has not yet been detected locally but it is present in the Americas – Brazil and Puerto Rico - and though we are already faced with cases of the pandemic influenza H1N1, it is preventable and manageable. There is however a great need for health professionals to be alert and prepared to act to prevent and manage the viruses. The symposium is one of the ways that The UWI is owning its responsibility for providing information and guidance to the healthcare sector and the wider community on health-related issues,” said Professor Terence Seemungal, Dean of the Faculty of Medical Science. The following are highlights from the presentations made by members of The UWI medical faculty. Dr. Christine Carrington Professor of Molecular Genetics and Virology, a. She presented a paper entitled ‘Zika virus in the Americas: A new challenge for Trinidad and Tobago’ b. She mentioned that ZIKV, the causative agent of Zika fever, is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that is currently emerging in the Americas. The virus was first isolated in 1947 in Uganda, and prior to 2015 outbreaks was confined to Africa, Asia, and more recently Micronesia. In 2015 Brazil reported local transmission of ZIKV and has now recorded more than 1.5 million cases. The virus has recently spread to countries neighbouring Trinidad and Tobago (T&T) including Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and Barbados, and has been reported in 21 countries including six Caribbean islands. c. Zika fever (which develops in about 25% of infected individuals) is a short, self-limiting febrile illness with severe complications but fatalities are rare. However, there is evidence from the Brazilian outbreak to suggest that the virus is associated with a more than 20-fold increase in the number of cases of microcephaly in newborns, as well as with a condition known as Guillain-Barré syndrome. There is no specific treatment or vaccine currently available for ZIKV, so protection against mosquito bites the best form of prevention. Avoiding pregnancy during high risk periods has also been recommended. d. At the time of her presentation she noted that Zika virus had not yet been reported in T&T. However, given that (as elsewhere in the region), Aedes aegypti is endemic and our local population is immunologically naïve to ZIKV, it is surely only a matter of time before transmission is confirmed in T&T. She discussed the nature and origins of ZIKV, its epidemiology in the Americas, factors underlying its emergence and methods used for diagnosis. She also reviewed the current evidence for its association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, and the overall public health implications. e. In reviewing ‘Zika in the America’ she informed the audience that Zika virus arrived in the Americas in 2015 with cases documented Brazil and Colombia. Largest ZIKV outbreak in the Americas reported in 2015 in Brazil with 1.5 million cases. Cases have been reported in 21 countries in the Americas and the first case in the USA reported in Texas in 2016. f. Suggested that human activities may have contributed to the emergence of ZIKV induced cases. These include globalization and urbanization: rapid and extensive global transport, increased populations in urban areas; habitat destruction, forest encroachment, intensive farming and other agricultural activities. g. Dr Carrington summarized the impact of ZIKV as being economic losses associated with morbidity, decrease in tourism, serious conditions (microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome) h. In Brazil, in 2015 alone there were approximately 3,500 (20 times the usual number); Increase in cases occurred within months after ZIKV being identified, Virus detected in amniotic fluid in pregnant women carrying microcephalic babies; i. Precautions suggested include: Women encouraged to delay pregnancy in some countries, travel warnings issued for pregnant women, more research needed to confirm link, determine most vulnerable period of pregnancy and risk. j. Public health control measures: Since there is no known vaccine or treatment, making mosquito control the key measure. k. Mosquito control suggested to include: Reduce mosquito population, reduce breeding sites, spraying, public education, protection, bed nets, insect repellants, extra care for pregnant women

Dr. Michelle Ramjohn Specialist Obstetrician/Gynaecologist, Mt. Hope a. She presented a paper entitled ‘Why Pregnancy is highrisk for H1N1 and Zika?’ b. Pregnant women are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality with the H1N1 virus. Newborns born to mothers who develop severe illness are at increased risk of prematurity and low birth weight. Daily new information is emerging about the effects of ZIKV in pregnancy requiring us to formulate new strategies to combat this potentially crippling disease. c. She referred to a statement by the El Salvador Deputy Health Minister, Eduardo Espinoza that ‘We’d like to suggest to all the women of fertile age that they take steps to plan their pregnancies, and avoid getting pregnant between this year and next.’ d. Information on ZIKV available to date was identified as:

e. The speaker identified the symptoms of ZIKV infections in pregnant women as:

f. Recommendations made by the presenter are as follows:

Dr. Windsor Frederick Lecturer, Child Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, a. He made a presentation entitled ‘Critical Issues in the Paediatric age group’ b. He suggested that ZIKV virus is expected to reach our shores in the near future. There may be challenges in assessment and management of patients with ZIKV due to the simultaneous circulation of the Dengue and Chikungunya viruses. This would be especially so in infants due to the non-specific nature of disease presentation in this age group and the similarities in presentation of the viruses mentioned. c. If a causative role for ZIKV in these cases of congenital anomalies, is confirmed this may have significant implications for the potential burden that ZIKV may place on the health care system. d. Affected infants may have complex neurodevelopmental issues which would require thorough assessment and long term, multidisciplinary, follow up. e. Identified the challenges posed by ZIKV as the non-specific presentations in younger children and infants, distinguishing between ZIKV cases and dengue fever, reports of possible congenital abnormalities due to vertical transmission. f. He highlighted possible complications of ZIKV as possible association with Guillain-Barre syndrome and other neurological complications-– meningitis, meningoencephalitis, myelitis g. Recommended the following management measures for ZIKV cases: supportive care, rule out other serious conditions, attention to oral intake and hydration status, thorough evaluation and follow up of patients with the possible effects of vertical transmission.

|

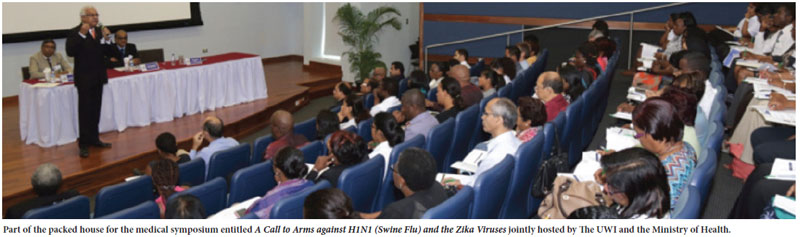

Healthcare professionals and leaders from both the private and public sectors convened on 31 January at the Teaching and Learning Complex, Lecture Theatre A, The University of the West Indies (The UWI) for a medical symposium entitled ‘A Call to Arms against H1N1 (Swine Flu) and the Zika viruses.’ This symposium was hosted as a joint effort between The UWI’s Faculty of Medical Science and The Ministry of Health. The one day symposium was intended to facilitate discussion and provide health professionals with the facts needed to prepare them to manage the public health risks associated with the viruses.

Healthcare professionals and leaders from both the private and public sectors convened on 31 January at the Teaching and Learning Complex, Lecture Theatre A, The University of the West Indies (The UWI) for a medical symposium entitled ‘A Call to Arms against H1N1 (Swine Flu) and the Zika viruses.’ This symposium was hosted as a joint effort between The UWI’s Faculty of Medical Science and The Ministry of Health. The one day symposium was intended to facilitate discussion and provide health professionals with the facts needed to prepare them to manage the public health risks associated with the viruses.