When you picture the words superstar architect - what comes to mind? When you picture the words superstar architect - what comes to mind?

This was the question on the minds of the crowd goers in the standing room only Teaching and Learning Complex at UWI St Augustine last December.

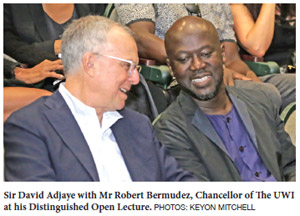

Architects, designers, engineers and other curious patrons came out to the Distinguished Open Lecture by Sir David Adjaye OBE to hear him speak on the topic “Building Publics”. The lecture was made possible by the Open Lectures Committee in collaboration with the Trinidad and Tobago Institute of Architects and the Board of Architecture of Trinidad and Tobago.

The anticipation was palpable as people scurried to find seats during the welcome message of Chair of the Open Lectures Committee and Master of Ceremonies for the evening, Professor Christine Carrington. Her words reminded the audience of Adjaye’s incredible reputation:

"Over the years, we have had a diverse selection of very knowledgeable and engaging speakers, all at the forefront of their fields, but I suspect that this is the first time that we’ve had a speaker who is routinely, in all sincerity, referred to as a superstar."

That’s putting it mildly. Adjaye was dubbed an “architectural visionary” by Time magazine and in 2017 made their list of “100 Most Influential People”, the only architect among them. In 2009, his design practice, Adjaye Associates, won a competition to design the prestigious 29,000 sqm Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (2016). Even his residential projects make history, such as when he designed the private house in Ghana of Kofi Annan, the late former UN Secretary- General, where he built a temperature-controlled structure using not one luxury material.

Looking at the faces in the audience become awash with awe, I wondered, with such an astronomical pedestal, what could Adjaye possibly teach our small island? Then he graced the stage, his British-Ghanaian accent steeped in soft exactness. He discovered very early on, he assured us, that “architecture could not just make buildings, but make meaning in our society and could be something to express the unique continents and the unique culture around the world”.

Through a series of slides, Adjaye simply talked his way through his architectural self-exploration process. Starting at the beginning of his career where he looked at the continent of Africa as a magnifying lens for the way human habitation has adapted and therefore how architecture has adapted. He visited all 54 countries in Africa, taking photos as he went along, to imagine an Africa without borders that was representative of the entire world’s geographies. It took 11 years to create a vast satellite map depicting the ways the geographies of the land affected the form of the architecture throughout the continent. Through this methodology of creating buildings that reflect the climate and culture of a society, Adjaye showed that for architecture to be light years ahead it must look back and give back.

This was the case in the construction of the super-scaled Moscow School of Management, SKOLKOVO, in 2010 – a massive 700,000 sq ft university campus that married the look and feel of Russian architecture from 100 years ago with the intricate pattern-making found in African art. The razzle-dazzle of Adjaye’s design came not only from its beauty, but also from the thoughtful functionality of it, “A full campus in one building - dorms, gyms, classrooms, administrative support and a hub for students from Africa, Europe and the US who now come to Russia to learn about business”. This was the case in the construction of the super-scaled Moscow School of Management, SKOLKOVO, in 2010 – a massive 700,000 sq ft university campus that married the look and feel of Russian architecture from 100 years ago with the intricate pattern-making found in African art. The razzle-dazzle of Adjaye’s design came not only from its beauty, but also from the thoughtful functionality of it, “A full campus in one building - dorms, gyms, classrooms, administrative support and a hub for students from Africa, Europe and the US who now come to Russia to learn about business”.

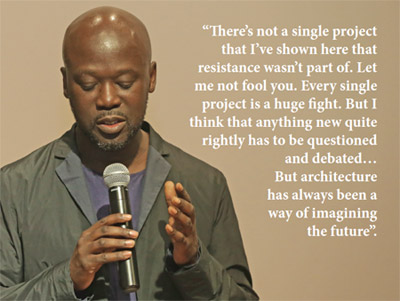

In the last part of the evening during the Q&A session, Adjaye brought the audience back to earth, revealing that creating visionary and inclusive public spaces is not at all an easy endeavour, “There’s not a single project that I’ve shown here that resistance wasn’t part of. Let me not fool you. Every single project is a huge fight. But I think that anything new quite rightly has to be questioned and debated…But architecture has always been a way of imagining the future”.

In the same way, he emphasised that his ability to collaborate with artists when designing buildings was because they see the future too, “A culture that is disconnected from its artists is a lost culture. I’m always inspired to bring in artists because they ponder civilization and meaning. They are kind of an amazing resource that is underused”. The room exploded with resounding applause.

Sitting in the fluorescent light of the auditorium after the lecture, I thought about the natural light that diffused throughout Sir David Adjaye’s buildings giving the spaces a chance to breathe and the public a sense of ease. Perhaps even in the throes of recession and hardship, Trinidad and Tobago could follow Adjaye’s North Star to find the solution within ourselves and reflect, restart and rebuild.

Sir David Adjaye’s work can be seen at the Adjaye Associates website: http://www.adjaye.com/

Jeanette G. Awai is a freelance writer, stargazer and marketing and communications assistant at The UWI St Augustine Marketing and Communications Office. |