Solar geoengineering can deflect from climate control efforts, say scientists

Broadly speaking, geoengineering is a term used to describe a variety of technologies aimed at manipulating the Earth’s natural systems on a large scale to counteract climate change.

Solar geoengineering controversially seeks to use a series of methods that essentially attempt to reflect some of the sun’s rays back into the stratosphere, thus limiting its warming effect.

One proposal is to inject miniscule reflective particles into the stratosphere - like spraying an aerosol - using airplanes or balloon-type devices. It is based on the known cooling effect of volcanic eruptions on climate systems. Already, the recent eruption in Tonga has invoked predictions of a reduction in temperatures over the next few years.

Other ideas include marine cloud brightening to reflect more sunlight back into space; cirrus cloud thinning, thereby reducing their capacity to trap more heat; and space mirrors strategically placed to reflect sunlight away from the planet.

Sounds like science fiction, doesn’t it? The difference is that there is no way to script the outcomes, and the probability of unintended consequences is remarkably high.

So high, that a group of scientists and other experts on the governance implications - political and environmental - have come together to call for an “International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering.”

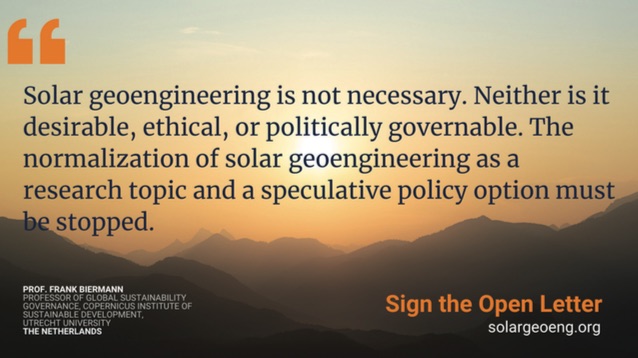

The call, issued as part of an academic paper compiled by 19 members of this coalition, was published on January 17, 2022, as an open letter, and carried the signatures of 63 scientific supporters. The lead author of the paper is Professor of Global Sustainability Governance, Frank Biermann, of the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University in The Netherlands. It is a demand for “immediate political action from governments, the United Nations, and other actors to prevent the normalisation of solar geoengineering as a climate policy option”.

It is a compelling document, raising what they consider to be three “fundamental concerns” regarding the increase in proposals for pursuing this fledgling technology.

Their first argument deals with the ambiguity surrounding the risks. “Impacts will vary across regions, and there are uncertainties about the effects on weather patterns, agriculture, and the provision of basic needs of food and water.”

The second is perhaps the most sobering of the treatise, dealing not so much with the science, but the political implications. They warn that pinning hopes on the success and availability of these technologies threaten commitments to mitigation of global warming.

“The speculative possibility of future solar geoengineering risks becoming a powerful argument for industry lobbyists, climate denialists, and some governments to delay decarbonisation policies,” they warn.

It is not an idle warning, nor is it an alarmist position. With the recent COP26 just a few months ago, the evidence of political manipulation and reluctance to implement pledges made over previous summits of that nature provide ample evidence that, given a chance to slide away from actively pursuing carbon emission reduction policies, the majority of nations—especially the biggest offenders—will. Dr Hugh Sealy, an environmental scientist at Cave Hill, who has attended several of these summits, knows how politics influences outcomes, but he does not think the likelihood of investment into the technology is strong. “I sit on the CDR Forum, which is an informal international group looking at carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies. Solar geoengineering or solar radiation management is failing to gain credibility.”

The coalition’s third point is that “the current global governance system is unfit to develop and implement the far-reaching agreements needed to maintain fair, inclusive, and effective political control over solar geoengineering deployment. The United Nations General Assembly, the United Nations Environment Programme or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change are all incapable of guaranteeing equitable and effective multilateral control over deployment of solar geoengineering technologies at planetary scale. The United Nations Security Council, dominated by only five countries with veto power, lacks the global legitimacy that would be required to effectively regulate solar geoengineering deployment.”

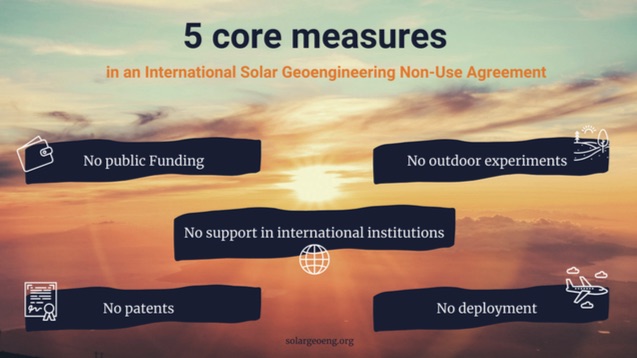

Having laid out their concerns, they identified five core measures for which they would like governmental action.

They make it clear that the intent is not to “prohibit atmospheric or climate research as such,” neither would it place “broad limitations on academic freedom”. The focus would be “solely on a specific set of measures targeted purely at restricting the development of solar geoengineering technologies under the jurisdiction of the parties to the agreement.”

Their paper and their call has stimulated a fierce debate over several issues. Many of the arguments focused on labelling it as “undemocratic” and “illiberal”—echoing the tone of those complaining about pandemic restrictions and mandatory vaccines.

One voice that surfaced on January 26 was that of Holly Buck, writing an opinion piece for the online MIT Technology Review under the heading, “We can’t afford to stop solar geoengineering research”. Questioning the distinction between research and development or deployment, Buck seems to go along with the reasonable nature of the concerns, but points to the dangers of making “research unpalatable”, saying that the result of making it unattractive for “any serious research groups” to proceed given the “intense social pressure” might further increase the risks of unethical use. It won’t mean that such research will end, she said, but that “it means that researchers who care about openness and transparency might stop their activities, and the ones who continue might be less responsive to public concerns.”

Funding will continue from those who don’t care about public opinion, like “private actors or militaries—and we might not hear about all the findings. Autocratic regimes would be able to take the lead; we might have to rely on their expertise in the future if we’re not successful in phasing out fossil fuels. And scientists in developing countries—already disadvantaged in terms of participating in this research—may be even less able to do so if international institutions and philanthropies are not providing funds.”

But she falls back on one of the points the academics had raised as a source of concern: the question of regulation. She suggests that “national funding agencies can structure research programmes to examine the potential risks and benefits in a comprehensive way, making sure to give full attention to everything that could go wrong”.

I contacted Professor Biermann for his comment on this opinion. He had already posted his response. Welcoming her more reasoned response, he countered that, “The key problem is not governance of research but governance of deployment. If one has no acceptable vision for the latter, even the most reflexive and well-considered research governance will not save the day. More than eighty percent of humanity live in the Global South; it follows that countries in the Global South would need to have effective control over any deployment of solar geoengineering. Would the US Senate agree to this?”

Noting that the real world of “capitalism and global power structures is different” from the scientific world, he raised the issue that one “group of powerful actors”, those heavily invested in fossil fuels, would benefit most from extra time to exploit coal, oil, and gas.

“As long as there is no clear scenario for sustained long-run global governance of solar geoengineering deployment in a fair and inclusive manner, research to develop solar geoengineering technologies is playing with fire. Solar geoengineering researchers are well-intentioned, and they deserve respect. They also declare themselves to be opposed to deployment at this stage. Yet their personal views on eventual deployment will become irrelevant once the technology exists. They engage in a highly risky project that they will not be able to control and master. Eventually, other powerful actors will take over. At present, the genie is still in the bottle. Don’t let it out,” he ended.

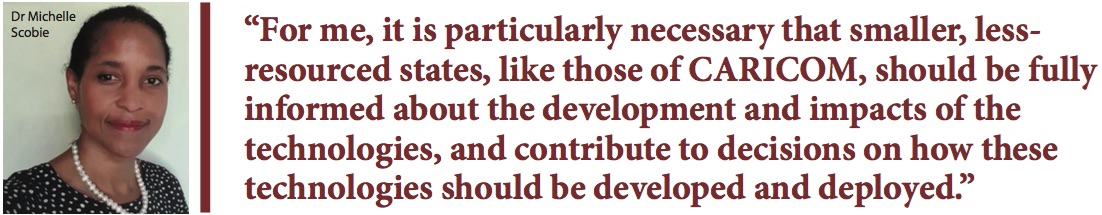

Among the academics contributing to the initial article, was Dr Michelle Scobie, a senior lecturer in International Law at the Institute of International Relations at the St Augustine Campus of The UWI. Given the estimate that 80 percent of humanity lives in the geographical area known as the Global South, her knowledge was vital in the preparation of the document. Scobie is a global environmental governance scholar, one of a very few in the Caribbean, who has been researching and presenting “perspectives on international relations and environmental governance,” many of which, she says, “revolve around the intersection of small states, international affairs, environment, justice and development”. She has discussed this in her 2019 book, Global Environmental Governance and Small States: Architectures and Agency in the Caribbean.

An example of the messaging materials being used by the scientists and other experts calling for an international non-use agreement on solar geoengineering.

“I am part of the writing team for this piece because of my concern that these new SRM [solar radiation management or modification] technologies—that have global repercussions well beyond the states wherein they are developed—should be done fairly and equitably. At present, the well-intentioned scientists and a small minority of states are moving forward with research and deployment plans without consulting with most of the planet. This cannot be fair. One of the key principles of environmental law and governance is that prior informed consent is needed from stakeholders before technologies or materials that may be potentially harmful are introduced into local spaces,” she said. “For me, it is particularly necessary that smaller, less-resourced states, like those of CARICOM, should be fully informed about the development and impacts of the technologies, and contribute to decisions on how these technologies should be developed and deployed.”

She hones in on the necessity for protection of the rights of those who have been traditionally most affected, but least consulted on global decisions.

“At present, there are no governance frameworks or forums for global oversight of SRM. The article we jointly prepared inter-alia throws light on this serious problem. It is a problem with the global governance of the environment that I have called attention to, also in other areas of my research over the years.”

The team believes that investments can be more usefully made in helping nations to reduce carbon emissions. It is a critical aspect of the planet’s quest for survival, and they say that solar geoengineering is not necessary at this point. Like the mirrors proposed to deflect the sun’s rays, it avoids treating the causes of global warming, and may simply mask the effect of greenhouse gas emissions until it is too late.