Looking to the mountains of the Northern Range in dry season, it’s not uncommon to see plumes of smoke rising up as fires alight through the parched landscape. Forest and bush fires, exacerbated by human activities in these green areas, have long been a part of life for those who live along the northern stretch of Trinidad.

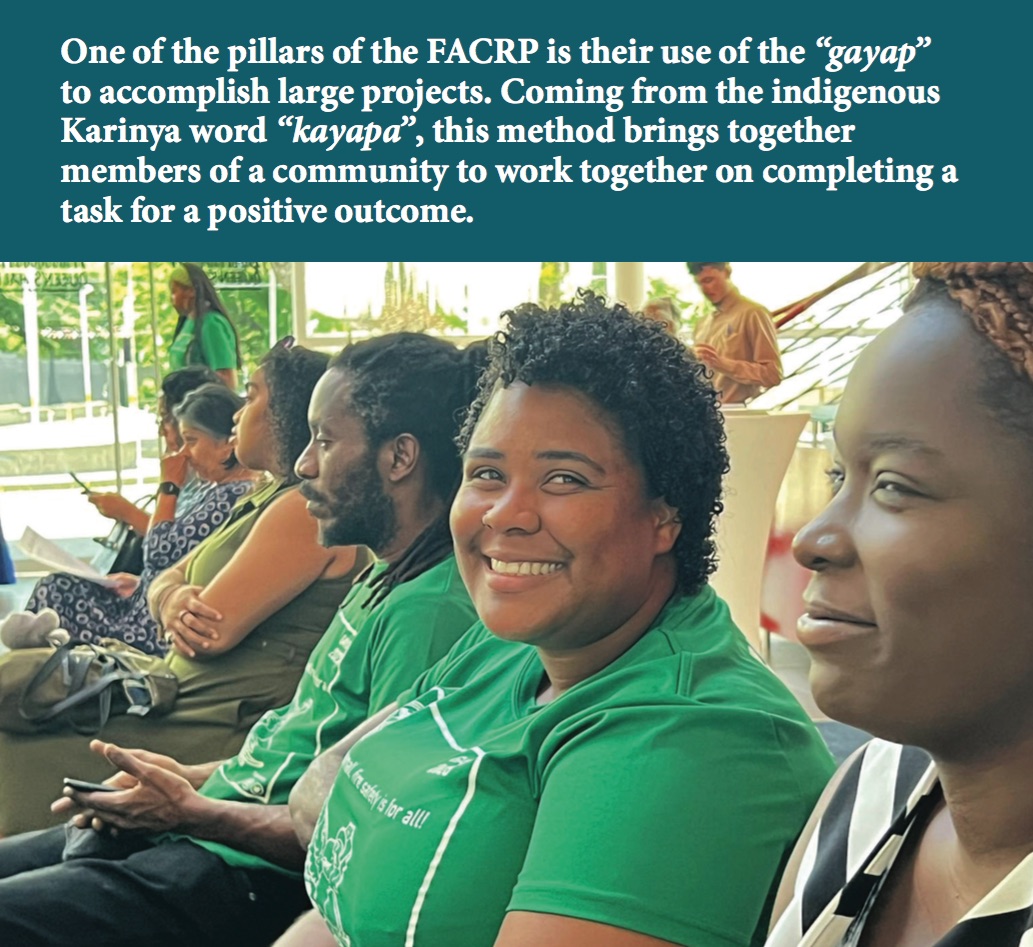

The Fondes Amandes community, deep within the St Ann’s valley, has found ways to come together and manage the continuing project of protecting and rehabilitating the landscape around them over the past four decades, fighting forest and bush fires, and reclaiming the watershed for its natural ecosystem to thrive. Now, the Fondes Amandes Community Reforestation Project (FACRP) is taking their wealth of knowledge on community building and conservation, and finding ways to share it with other groups learning how to tackle community issues as a collective.

For Kemba Jaramogi, her childhood, growing up in the Fondes Amandes watershed, was characterised by a state of constant vigilance.

“It is something that is woven into your DNA at this point, that as soon as you see or smell smoke, you need to find it,” says Kemba. “Because we were so hyper-sensitive when we were younger, now I can tell exactly what’s burning if I smell a fire.”

She can differentiate the scent of burning plastic, from garbage, from leaves, from cloth. Kemba is the second generation of her family to work in this field— in 1982, her father, Tacuma Jaramogi, and mother, Akilah Jaramogi, established the FACRP.

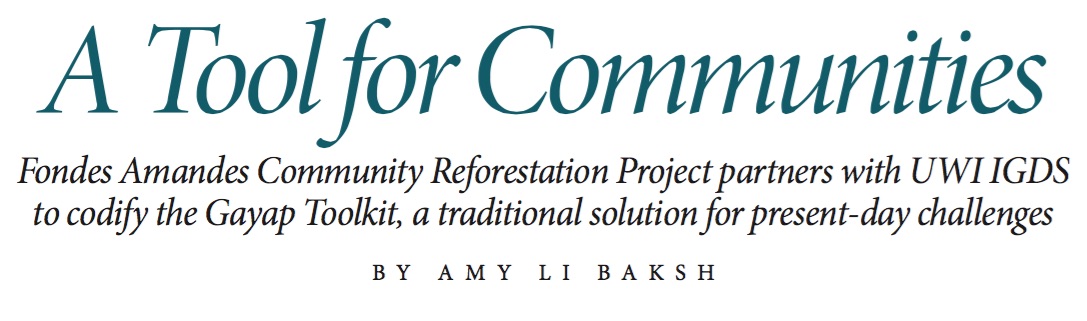

One of the pillars of the FACRP is their use of the “gayap” to accomplish large projects. Coming from the indigenous Karinya word “kayapa” (a term which describes the tradition of people getting together to complete a huge task), this method brings together members of a community to work together on completing a task for a positive outcome. The Jaramogi family has been hosting gayaps informally since the 1980’s, but when Tacuma Jaramogi passed to ancestorhood in March 1994, there was a need to begin formalising this process. Akilah sought to begin hosting a yearly gayap in his memory, where members of the community could come out, work on a project, and also learn more about conservation and the indigenous and Merikin knowledge that she had brought with her from her upbringing with the company villagers in South Trinidad.

“They made the perfect team,” says Kemba, “having that kind of local knowledge, indigenous knowledge, traditional practices, that connection to the land. So, they said they had to do something to change the pattern of bush and forest fires every year.”

In the 1990’s, Dr Innette Cambridge, a lecturer in the Department of Behavioural Sciences at UWI St Augustine, was the first from the institution to build a connection to FACRP. In order to teach her classes about sustainable development and seeing these theoretical ideas in action, she took her students out to Fondes Amandes. Now, FACRP and UWI have partnered on a series of projects over the years, the latest of which is the documentation and formalisation of their gayap process, through the Gayap Toolkit.

Currently, Dr Deborah McFee, Institute for Gender and Development Studies (IGDS) Outreach and Research Officer, has been leading the collaborative effort to share with FACRP some of the experience of the IGDS on gender and its relationship to climate change, while learning from the NGO’s knowledge base.

“It’s very much a reciprocal relationship,” says Dr McFee. “Fondes Amandes is a woman-led civil society organisation, and we have been working with them for a long time... IGDS has an outreach and research team, and when we work with civil society, generally it’s about bringing our technical knowledge to the table and working with our partners to have an understanding of the ways in which these concepts become realities on the ground.”

Today, FACRP is well-established in the civil society space as an expert in what they do. But as a woman-led organisation, it was an uphill battle to get there.

“Fifteen or so years ago, you walk into a space and you have to do a lot to convince people about what you’re talking about. Typically, it’s a male-dominated space,” says Kemba. “You had to work twice as hard to prove you know what you’re talking about.”

But over their 40-plus years of work, they have shown their expertise. “We’ve demonstrated consistency in the work that we do. Consistency and transparency… We have that respect because of the work that we do. But it wasn’t always easy.”

The collaboration between IGDS and FACRP has yielded benefits for both sides, and the communities they work with. In 2019, they finished a three-year project developing the Gender and Climate Change Toolkit which looked at the intersections between gender and climate change and incorporating gender focus into climate change programming— an initiative supported by the Commonwealth Foundation.

“Following that toolkit, we had an opportunity with the Commonwealth foundation to do a small project illustrating our understanding of the intersections of gender and climate change. Because of that partnership we realised that it would be nice to collaborate with IGDS to inform us— we could learn from them on gender and they could learn from us on the environment side of things. Co-learning and co-partnership was really powerful and impactful,” says Kemba.

Through that project, they were able to plan workshops with secondary schools, starting up a conversation that many of the young minds would not have otherwise been exposed to. They addressed issues like the different considerations that have to be made during disasters when it comes to gender.

For example, in disaster shelters, there is a priority made for women, girls and boys to be hosted, while men might be considered more suited to be out in the field.

“They don’t look at ability rather than gender. Some women might prefer to be out in the field fighting fires, and some men might be better at coordinating in the kitchen or doing a children’s programme, or being a nurse or doctor. So, it was so great to see a lot of the young men have eureka moments when they realise that gender discourse is something that they should be engaged in, and they are also represented in this, and we need their voices to lobby for areas where they themselves are disenfranchised,” says Kemba.

As the teams worked together on further projects, the topic of the annual gayap came up in conversation, and Kemba was asked if she had a document outlining the specifics of how it was run. She realised that though they had some documentation they had built up over the years, there was no official document that contained all the information needed to understand the meaning of what a gayap could be and how to best utilise this tool for larger-scale problem solving within communities.

“The toolkit is pulling together how you do a gayap,” says Dr McFee. “The gayap doesn’t necessarily have to be about climate change. It is about how you pull the community together. [The Gayap Toolkit] answers things like: what is the purpose of the gayap? Why would you host a gayap? How do you ensure you’re inclusive in terms of the work that you do? It is an ideal experience of the university being in service, not to but in service with our community.”

As part of the development of this project, there was also a pilot initiative where eight organisations were trained in how to use the Gayap Toolkit, and then took that knowledge and attempted to plan and execute their own gayaps to solve problems in their communities.

“The gayap is not just for bush and forest fires,” says Kemba. “The gayap can be used for anything, and it is keeping those traditions alive that helped our fore-parents survive. Back in the day, people had a gayap to build a house – now you must have a lot of money and contractors to do so. People in a hillside community might have a gayap day to tote materials up the hill for building. If a road caved in you might have a gayap to put the road back together. So, there are so many different ways that you can use a gayap, because gayap is all about bringing people together to work for a positive cause.”

Right now, the toolkit is in the process of being completed and made available digitally for dissemination, although Kemba has hopes that they will be able to get some much-needed funding to publish physical copies as well. They have also put together a documentary on the experiences their gayap participants have had, to be screened this year in partnership with the Trinidad And Tobago Green Screen Environmental Film Festival.

“We hope to continue to share and promote, especially when working with disaster responses,” says Kemba. “The impact of climate change is becoming more and more critical, and more devastating. We really need to appeal to our community energy and efforts to not break up because of disasters but to gel together and really find long-term solutions and short-term actions that could really benefit everyone as a community.”