|

|

|

|

January 2011

|

In most instances ‘cooling’ is used traditionally as preventative medicine (prophylactic) to bring the ‘body back in balance’ in ‘hot’ conditions. ‘Hot’ diseases appear to be associated with fever, infectious skin manifestations (such as rash and ringworm) and inflammatory conditions such as hives. Traditionally, ‘hot’ states required ‘cooling’ treatments, which included medicinal plant preparations that supposedly restored the body’s balance. We hypothesized that humoral medicine was still being actively practised in rural Trinidadian communities and undertook to conduct an ethnobotanical survey to document the use of ‘cooling’ medicinal plants, as well as plants used for the treatment of fever, a ‘hot’ humoral state. A survey was conducted in 50 rural communities to include 450 households by face-to-face interviews over the period October 2007 to July 2008. This was done as part of the larger Caribbean-wide TRAMIL (Traditional Medicine in the Islands) network. We restricted our survey to rural agrarian communities where we assumed that there would be a higher incidence of use of local herbal remedies from the garden or backyard and preservation of traditional knowledge.

Twenty households from each of the 50 communities were conveniently selected and the most knowledgeable person in the household was interviewed on the use of herbal medicines. In most instances, respondents were the eldest female in the household who was often responsible for the healthcare of the family. This is the first extensive ethnobotanical study done in Trinidad, and to our knowledge, the English-speaking Caribbean, that quantifies the extent of traditional use of medicinal plants as ‘cooling’ and for the treatment of fever in rural communities.

These findings confirm that humoral medicine remains popular in rural communities throughout Trinidad. The indigenous flora of Trinidad is mainly neotropical. However, during the colonial period, numerous plant species of economic and horticultural importance were introduced into the island, some of which become major plantation crops. It is therefore not surprising that almost half of the species found in this survey are also exotic species, such as Aloe vera or Citrus sp. It is uncertain to what extent the Amerindians’ use of the indigenous flora for medicine influenced the use of the indigenous species for medicine found on this survey by the transplanted population from mainly Africa and Asia. Albeit all the species are mainly common roadside weeds or forest species which are not threatened or endangered. It would be difficult to trace with certainty the routes whereby humoral medicine reached the island of Trinidad.

Although Macfedyena unguis-cati (Cat’s Claw) was the most commonly used plant for ‘cooling’ in Trinidad there is very little research done. In animal models for pain and inflammation an extract of Stachytarpheta jamaicensis (Verven) significantly reduced sensitivity to pain and experimentally-induced inflammation. Senna alata (candlestick plant), native to tropical America, is commonly used to treat skin conditions such as fungal growth, pimples and ringworm. In Trinidad its use as ‘cooling’ in bush teas could be related to the preventative effects against skin conditions related to these ‘hot’ conditions. Human and laboratory studies support the traditional use of candlestick plant in the treatment of skin conditions caused by microbial organisms.

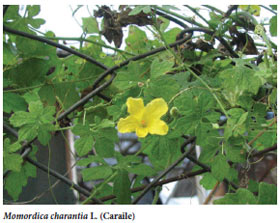

In classical West Indian folkloric tradition a ‘purge’ is often given to ‘clean out the insides and purify the blood’ and to prevent the occurrence of disease which oftentimes manifest as ‘hot’ skin conditions. This purge often included bush teas which may include candlestick plant to cause diarrhea. A clinical study using people who complained of constipation for at least three days showed that a bush tea from candlestick plant produced significant relief after 24 hours. Caraile (Momordica charantia) was also identified as a useful plant for ‘cooling’ in Trinidad and is traditionally used to treat skin conditions including rash, furuncles (boils) and hives. For skin There is much laboratory and animal-based research to support the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and related biological activities for most of the plants identified for ‘cooling’ and its associated indications. However, caution must be taken as most of this research was done in using laboratory experiments or animals which do not represent the ‘real’ situation in the human body. Clinical studies in humans must be done to determine whether these remedies are in fact safe and effective. Our survey has identified medicinal plants for traditionally labeled conditions which could be partly explained by modern medical terminology. However, the preliminary support of laboratory and animal-based studies should be used as a platform from which clinical studies in humans could be done to determine the effectiveness and safety of herbal preparations used as ‘cooling’ and for fever. It is possible that these research efforts may provide alternative and/or complementary approaches for healthcare provision in the Caribbean.

|

For many centuries, European and Asian societies used the concept of humoral medicine to explain health and wellness as the delicate balance between ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ spheres in the body. Disease was defined as an imbalance between these spheres, with associated excessive ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ conditions. Although modern evidence-based medicine has effectively replaced humoral medicine in the Western world, remnants of humoral medicine (pertaining to body fluids) and its practice remain alive and well in many parts of the developing world, including Trinidad.

For many centuries, European and Asian societies used the concept of humoral medicine to explain health and wellness as the delicate balance between ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ spheres in the body. Disease was defined as an imbalance between these spheres, with associated excessive ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ conditions. Although modern evidence-based medicine has effectively replaced humoral medicine in the Western world, remnants of humoral medicine (pertaining to body fluids) and its practice remain alive and well in many parts of the developing world, including Trinidad.  A simple pilot-tested qualitative survey questionnaire was used to collect details, such as the plants being used, the part or parts being used, and forms in which remedies were made. Samples of live plant specimens were collected and placed in a plant press for preservation. These specimens were subsequently taken to the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago where they were dried, identified and accessioned to be filed with the main collections. Global positioning system (GPS) coordinates were also collected at the interview sites to locate respondents and plant specimens.

A simple pilot-tested qualitative survey questionnaire was used to collect details, such as the plants being used, the part or parts being used, and forms in which remedies were made. Samples of live plant specimens were collected and placed in a plant press for preservation. These specimens were subsequently taken to the National Herbarium of Trinidad and Tobago where they were dried, identified and accessioned to be filed with the main collections. Global positioning system (GPS) coordinates were also collected at the interview sites to locate respondents and plant specimens.  The survey found that 44 plant species belonging to 31 families were used for ‘cooling’ in 48 out of the 50 communities with 238 citations. Cat’s Claw, Verven, Candle Bush, Caraile and Shiny Bush accounted for a significant proportion of the citations (142 out of 238 or 40.9%). There were 109 citations for the treatment of fever from 41 out of 50 communities. A total of 28 plant species belonging to 19 families were identified, with Lemon Grass (Fever Grass) and Jackass-Bitters (sepi) accounting for 75 or 68.8 % of all citations.

The survey found that 44 plant species belonging to 31 families were used for ‘cooling’ in 48 out of the 50 communities with 238 citations. Cat’s Claw, Verven, Candle Bush, Caraile and Shiny Bush accounted for a significant proportion of the citations (142 out of 238 or 40.9%). There were 109 citations for the treatment of fever from 41 out of 50 communities. A total of 28 plant species belonging to 19 families were identified, with Lemon Grass (Fever Grass) and Jackass-Bitters (sepi) accounting for 75 or 68.8 % of all citations.  Although there are limited studies in humans to support the use of these plants as ‘cooling’ or any of the associated conditions, we conducted a review of published research to determine whether medicinal plants identified in our survey showed antibacterial properties and could be used to treat fever, pain and inflammation in laboratory and animal-based studies.

Although there are limited studies in humans to support the use of these plants as ‘cooling’ or any of the associated conditions, we conducted a review of published research to determine whether medicinal plants identified in our survey showed antibacterial properties and could be used to treat fever, pain and inflammation in laboratory and animal-based studies.  A study in humans demonstrated the effectiveness of ‘candlestick plant’ when applied directly to the skin as antifungal treatment for the flaky discoloured skin patches of pityriasis versicolor, caused by a yeast fungus. Other extracts of the bark of candlestick plant prevented the growth of the Candida albicans fungus, which causes thrush. It also prevented the growth of pus-forming bacteria responsible for triggering acne inflammation. These experiments were done in the laboratory.

A study in humans demonstrated the effectiveness of ‘candlestick plant’ when applied directly to the skin as antifungal treatment for the flaky discoloured skin patches of pityriasis versicolor, caused by a yeast fungus. Other extracts of the bark of candlestick plant prevented the growth of the Candida albicans fungus, which causes thrush. It also prevented the growth of pus-forming bacteria responsible for triggering acne inflammation. These experiments were done in the laboratory. conditions, the leaves are crushed and prepared as a poultice and applied directly to the skin; for preventative ‘cooling’ an infusion is used. Fevergrass was the most frequently cited plant in Trinidad for fever.

conditions, the leaves are crushed and prepared as a poultice and applied directly to the skin; for preventative ‘cooling’ an infusion is used. Fevergrass was the most frequently cited plant in Trinidad for fever.