|

|

|

|

July 2015 |

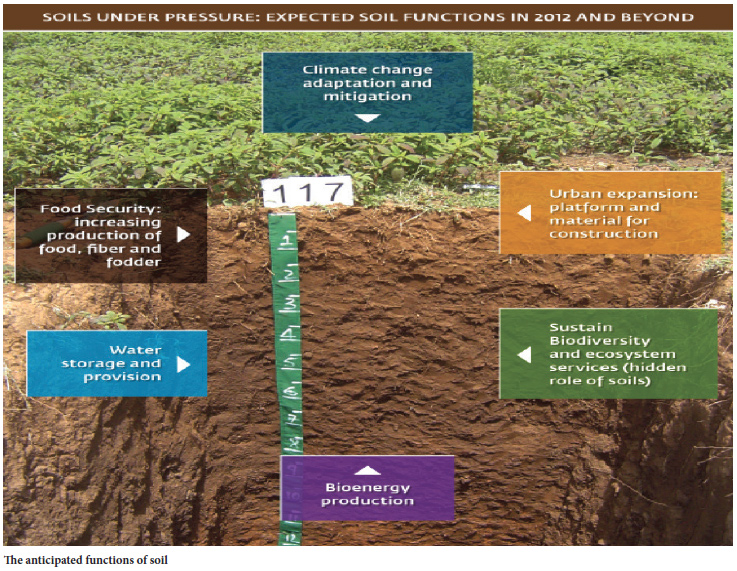

Soil is a ubiquitous resource that is forgotten from our personal and national agendas. To most, soil is indistinct from land. The latter represents a legal attribute of financial value. The Soil Science Society of America defines soil as “the unconsolidated mineral or organic material on the immediate surface of the earth that serves as a natural medium for the growth of land plants” and land as “one of the major factors of production that is supplied by nature and includes all natural resources in their original state, such as mineral deposits, wildlife, timber, fish, water, coal, and the fertility of the soil.” Regionally, policies exist that protect, regulate and strategize for the development of water, air, land, forest and biodiversity resources but our institutional libraries are devoid of any legal recognition of soil. Focus must therefore be placed on soil as a critical resource to sustainable development and a good place to start is to highlight the functions and pressures placed on soils in our economy:-

The United Nations designated 2015 the International Year of Soils with a rationale coming from the Global Soil Partnership (GSP) and the Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils (ITPS) under the auspices of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO): “The renewed recognition of the central role of soil resources as a basis for food security and their provision of key ecosystem services, including climate change adaptation and mitigation, has triggered numerous regional and international projects, initiatives and actions. Despite these numerous emergent activities, soil resources are still seen as a second-tier priority and no international governance body exist that advocates for and coordinates initiatives to ensure that knowledge and recognition of soils are appropriately represented in global change dialogues and decision making processes.” The realities of being a Small Island Developing State (SIDS) are reflected in the greater dependence on this limited natural resource. A reduction in the size and quality of this resource has more profound effects on our island as the land area per capita is reduced. A greater effort is needed on the part of the state and associated institutions to recognize and give deserved attention to soil resources. A five-pillar approach has been adopted by the GSP. These are:

Pillar 4 has been chosen for discussion first in this series as the other pillars are dependent on this one - the quantity, quality and availability of soil data and information. In the era where agriculture was socially and economically important, a comprehensive soil survey was performed (1960-70s) across the English-speaking Caribbean, with resultant soil maps (1:25,000) and narratives. It took another 40 to 50 years to digitize those maps which are still not readily available. This information remains the only cohesive geographic soils information available guiding decision-making, with fragmented studies mostly archived on the shelves of our libraries. Two concerns arise with respect to pillar 4: firstly, the age of the data and its applicability in our changing landscape. Land use has changed significantly over the past six decades, and this would have influenced soil properties. Additionally, the scope of the soil data is limited to mainly agriculturally related features. There is a need to generate (probably through a coordinated survey) new information about our soils and continue to add subsequent data (monitoring) to an information system supporting soil management. The second concern is not technical but administrative. Access (public or otherwise) to soil information is critical to foster sustainable management. Numerous stakeholders utilize soils and are guided by soil data. Where such data is not readily, available assumptions and best-fit scenarios are used to model soil behaviour, ultimately leading to poor decisions. Local projects coordinated by researchers at The UWI seek to collect, analyse and present agricultural data on an open access platform. This effort, if successful, should address the data availability issue and lend a hand to building a national soil resource inventory. However, sustainability of such efforts demands inter-institutional cooperation and coordination. The Latin American and Caribbean Regional Soil Partnership was launched in Cuba in 2013 with a similar aim under pillar 4, albeit with a regional focus. The group is scheduled to meet later this year to consolidate and apprise members of regional and global initiatives. Many more types of regional to community level initiatives directed toward saving our soils are needed for a turn-around in the value of this resource. It is clear however, that the starting point is an awareness of the threat to our soils so this discussion will continue. Dr Gaius Eudoxie is a soil scientist at the Department of Food Production, UWI St. Augustine. |