International project to monitor and mitigate the damage to our coastlines

Coastal erosion, the loss of land in coastal areas caused by the force of waves, tides and currents, has been eating up land, displacing communities and in some cases washing away whole towns over the long stretch of human history. For island states, disappearing coastlines can have a profound impact on work, habitation and even culture. The need to measure and mitigate the effects of coastal erosion are the driving force behind the Carib-Coast project.

Carib-Coast is an international initiative that focuses on coastal risks linked to climate change in the Caribbean. Dr Deborah Villarroel-Lamb, Lecturer in Coastal Engineering and Management at UWI St Augustine’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, is one of the local researchers on the project.

“Carib-Coast is vital to Trinidad and Tobago,” says Villarroel-Lamb, “like many islands in the Caribbean, because we suffer from the same climate change risks. This project will be of benefit to our islands and we can share our information through UWI.”

The study, officially launched in January 2019, is managed by the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM), a French geological institution which seeks to mitigate the effects of climate change.

BRGM’s Yann Balouin says the project stemmed “from the observation that almost all the islands of the Caribbean are subject to major natural risks, so there is a need for establishing networks of experts from all over the Caribbean who can work together to solve coastal management issues.”

The project, which also collects satellite imaging data on mangroves and coral reefs, focuses on Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Martin, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and Puerto-Rico.

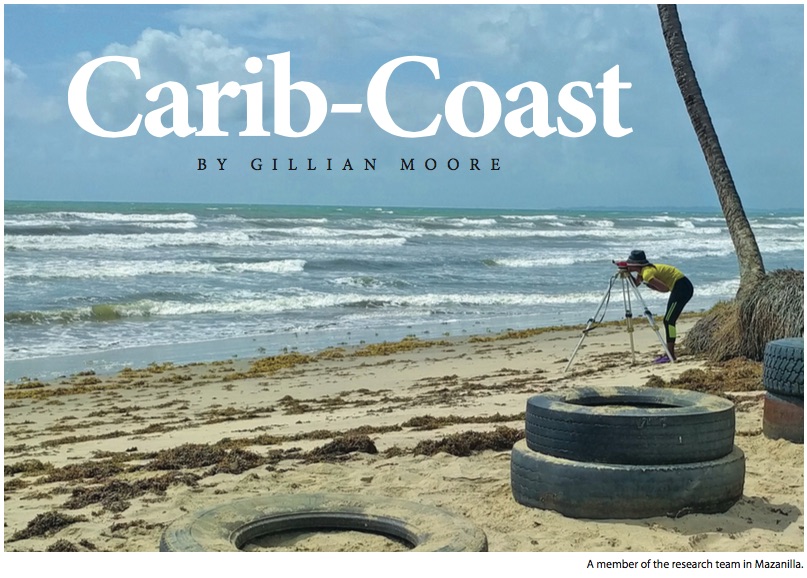

Villarroel-Lamb and her team have been measuring coastal conditions along the Manzanilla-Mayaro coast (the eastern edge of Trinidad). She said Carib-Coast aimed “mainly to solve the problem of the paucity of data readily available for decision making” in the region.”

“What drew me to the project was not just finding data on coastal issues,” the coastal engineer explained, but to see “what we can do in a collaborative effort” to solve those issues.

Villarroel-Lamb is part of a small team at UWI that includes Dr Junior Darsan and Dr Kegan Farrick of the Geography Department, as well as her student Shani Brathwaite, who is conducting research for her PhD in Civil Engineering. The Faculties of Engineering and Geography have together been monitoring the effects of hydrodynamics on Trinidad’s eastern coast.

Brathwaite says, “Coastal erosion should be a great concern to small island developing states like Trinidad and Tobago, as we depend on the coast for tourism, among other things. Our beaches play an important role, culturally, socially and economically.”

BRGM reached out to the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department, requesting to partner with them. For Villarroel-Lamb it was a natural fit, as she was already involved with coastal data collection, including a video camera system established at Mayaro which was funded by The UWI Trinidad and Tobago Research and Development Impact (RDI) Fund, and had already had experience working in conjunction with entities like the Institute of Marine Affairs (IMA) and the Coastal Protection Unit. IMA is also one of the partners on the Carib-Coast project.

IMA biologist Lester Doodnath says the organisation also has a lot to contribute to Carib-Coast: “We have been monitoring the coast for almost 40 years and we have a wealth of data. In terms of logistic support... we can provide trained personnel, facilities and a fleet of vessels.”

As part of the project, UWI received more than US$60,000 to purchase equipment, including another camera system, a location device (a pinger) for the wave gauge or the Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP), and a wave transmission device which will facilitate the retrieval of data remotely from instruments placed out at sea off the coast of Mayaro. The wave gauge can stay out at sea for up to eight weeks, fitted with a pinger to help track and locate it in case of storms. The video data collected in Mayaro will now be part of the input into the Carib-Coast project along with another similar video system to be funded by the Carib-Coast project in Manzanilla.

The project, says Brathwaite, involved spending “entire days at the beach, from 6am to 6pm,” capturing video data. Her research looks at the impact of wave run-up on beachfront properties.

“It’s challenging, fun, but a lot of work,” she says.

Her days at the beach however, have come to a temporary halt due to COVID-19. The project has experienced several delays.

Villarroel-Lamb says “filling gaps with science-driven data is fundamental. Once we address the data issues we can use it to look at solutions to coastal flooding, erosion and hazard mitigation”.

She says the next stage will involve a PhD candidate joining the team to help collate, process and disseminate their findings under her supervision. This, she says, “will afford us access to everybody’s data sets, because he will be pooling data from the whole region, tracking changes and trends.”

“The main idea is to pool resources across the Caribbean and put all the data into a central repository.” It can then be accessed for research, and used to create models for decision making,” says Villarroel-Lamb. “The only way we can go forward is through collaboration. We can’t do it on our own.”

She wants people to understand the consequences of coastal threats, including effects on property, fishermen’s livelihoods, the agricultural sector, pollution and the ongoing risks to reef and mangrove barriers.

“Data analysis is quite academic, she points out, “but it’s important to put it in a human perspective.”