|

|

|

|

June 2011

|

Fresh pigeon peas all year

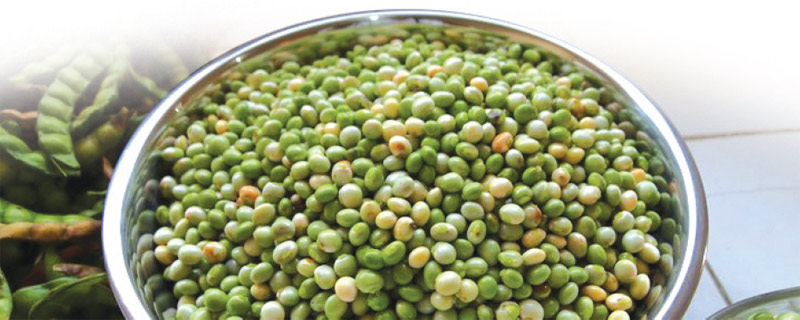

Nothing beats a pelau made from fresh pigeon peas, many a cook will declare – or a hearty stew or curry. In fact, a survey conducted by Albada Beekham, a former postgraduate student at The UWI, has indicated an overwhelming preference by consumers for the fresh version, which is not surprising to any pigeon pea connoisseur. But when the season is over, they have to resort to the dried version or even tinned pigeon peas. “Absence makes the heart grow fonder,” might be an apt phrase to describe the longing for this staple legume. The earliest breeding efforts on the pigeon peas crop in the Caribbean started in 1934 at the Imperial College for Tropical Agriculture (ICTA) in Trinidad, the forerunner to the St Augustine Campus. Research continued under ICTA’s successor, the Regional Research Centre (RRC), which was part of the Faculty of Agriculture in the fifties. This work, along with similar breeding efforts in Puerto Rico led to the development of the traditional varieties that are now consumed. However these varieties, planted by farmers and others in their backyard gardens, cannot meet the demand for fresh pigeon peas throughout the year. They are confined to flowering and production during the three-month span when day lengths are shorter – minimum day lengths between 12 to 14 hours are required for the initiation of flowering. These varieties also take from 180-280 days to mature, thus the customary June planting of pigeon peas is put into perspective. The crop is also low yielding due to its extended period of vegetative growth during the flowering period. Now research being done at The UWI has shifted the pigeon peas paradigm. You might now have access to fresh peas all year round, thanks to expansion of the breeding work that began more than 75 years ago.

The first generation or batch of improved varieties released in the early 1980s, included UW 17, UW 26 and UW 10. These created considerable interest since they were the first short-duration, year-round varieties in the Caribbean. Unfortunately, the shorter pod size, unfavourable seed quality attributes and the poor yields during the off-season made farmers reluctant to adopt them. The pods of the early varieties were shorter, narrower (making it harder to shell), had less seeds and were smaller in size (lower hundred seed weight). The seeds also had a lower starch content and higher levels of phenolics, leading to the greater nuisance of fingers being stained from shelling. Further improvements saw the development of a second generation or batch of pigeon pea varieties – UW 223, UW 263, and UW 282 – in the early part of the past decade (2000s). The new varieties produced pigeon peas in less than four months, as compared to the long wait of six months or more for the traditional varieties. They can be planted throughout the year and are expected to yield pigeon peas in 3-4 months. These combined higher off-season yields with better pod and seed quality characteristics, longer and wider pods with lower levels of phenolics and larger number of seeds per pod, as well as starchy, less fibrous seeds. Although the seed size was superior to the early varieties it was still falling short of that of the popular traditional varieties by 20% to as much as 60%. From a genetic perspective could the seed size be increased to an acceptable level among these new varieties, or is it an elusive dream? Building on the previous work of Albada Beekham on physical and biochemical quality traits and M.S.A. Fakir on yield, I undertook further research on the link or genetic relationship between seed size, other important pod quality features and yield. Findings indicate that seed size can be further improved without negatively affecting yield or seed number per pod, which is fantastic, because it appears that you can have year-round production and have the pod and seed qualities of the traditional varieties. Early results indicate that seed size can be improved by as much as 40% over the second generation varieties previously developed. If the study can be replicated over time and different parts of Trinidad the farmers and consumers can have their favourite pigeon peas dish, all year through. Albertha Joseph-Alexander has a BSc. in Botany and Biochemistry and an MSc in Crop Protection from The UWI. She is completing an MPhil in Plant Science. The research is entitled Morphophysiological characteristics associated with nitrogen fixation and yield in pigeonpeas. By Albertha Joseph-Alexander |