|

|

|

|

June 2015 |

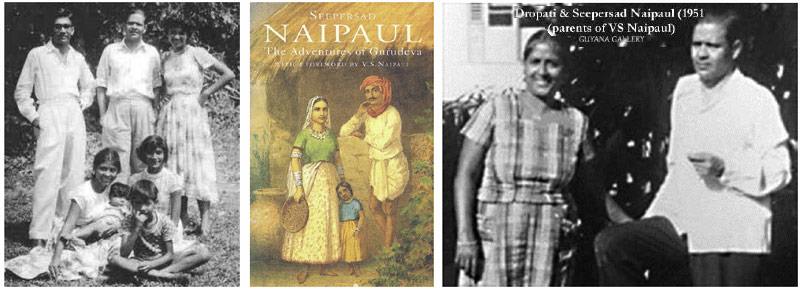

In Jahaji: An Anthology of Indo-Caribbean Fiction Frank Birbalsingh provides us with a useful note on which to begin this month’s engagement with the upcoming conference, Seepersad & Sons: Naipaulian Creative Synergies, which is being hosted by The Friends of Mr Biswas in conjunction with the Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies of the St Augustine campus of The UWI from September 6-8, 2015. Birbalsingh reminds us that “Indo-Caribbean imaginative writing… [began] with Seepersad Naipaul in 1943.” In addition, as I have argued, his stories “are set in the period of settlement and adjustment, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and allow for the investigation of the earliest pre-independence self-perceptions of post-indenture being and belonging” (A Caribbean Katha). This is no minor accomplishment. The study of narrative, as Ulric Neisser and Robyn Fivush argue in The Remembering Self, has been “one of the more prominent currents in late 20th-century intellectual life.” As a result we now know without a doubt that self-awareness, self-understanding, self-knowledge, self-assertion and so much more are dependent on the ability to narrate our lives and this ability is formed by the kinds of narratives to which we are exposed. In the hands of the creative artist, narratives can be powerful tools for social transformation. The transformation that Seepersad Naipaul’s work accomplishes is vividly depicted in the covers that V. S. Naipaul chose for the reproduction of his father’s 1943 collection (1976 edition). Putting paid to the idea of the helpless coolie peasant, the front cover depicts a young couple with a single girl child, whose postures, expressions and juxtaposition belie stereotypes of women’s passivity, rejection of girl children and patriarchal male violence. Reinforcing the image at the front, the image on the back cover of Seepersad with members of his family including his two young daughters shows a family in whom the same proud hauteur and self-confidence are immediately apparent. The third picture from the Guyana Gallery selected for reproduction in this article similarly reiterates the debunking of common stereotypes associated with the Indo-Caribbean, not only during the ‘coolie’ past but also in the present. In the stories moreover, “oppressed women, or girls really, are at the centre of Seepersad Naipaul’s concerns, and they serve in a sense as signifiers of the value of the community’s cultural patterns” (A Caribbean Katha). Perhaps for this very reason, in the foreword to the 1976 edition, V. S. Naipaul remarks that the original publication in 1943 “drew one or two letters of abuse from people who thought my father had written damagingly of our Indian community.” As many events marking the 170th year since the first arrival of the Indian indentured labourers this year indicate, the dominant discourse remains celebratory of the accomplishments of their descendants against the background of indentureship. In keeping with the ethos of our times, this generally translates into recognition of social status and fiscal well-being rather than less easily discernible albeit perhaps more important qualities such as honesty, perseverance and resistance to the valuing of status and money as the sole purpose of life. Seepersad Naipaul’s work asserts the latter. In fact in the depiction of the titular character, Gurudeva, Seepersad Naipaul exhibits severe reservations about the liberties that a certain amount of money and community status affords Gurudeva. Seepersad’s sons have written in a similar vein and their work, perhaps not surprisingly, has drawn similar if more widespread opprobrium. Despite this, in the preface to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Jean Paul Sartre claims that “The European elite undertook to manufacture a native elite. They picked out promising adolescents; they branded them, as with a red-hot iron, with the principles of western culture; they stuffed their mouth full with high-sounding phrases, grand glutinous words that stuck to the teeth. After a short stay in the mother country they were sent home, white-washed.” In their portrayal of such characters, the Naipauls’ work stood then and continues to stand now as a bulwark against the possibility of such characters lasting very long in the Caribbean. Moreover, as the recently concluded Indian Diaspora Conference on the UWI St Augustine campus highlighted, myths about the indentured labourers have proliferated abundantly. One of the most important tasks that the Naipauls’ work achieves is the debunking of myths. In this vein, one of the objectives of the conference ‘Seepersad and Sons’ is to distinguish between myth and reality in relation to the three Naipauls’ works and their contexts as Brinsley Samaroo has done in the article “The World of Seepersad Naipaul” for The ARTS Journal in March 2008, including the prominent myth which conflates the real life Seepersad Naipaul with the fictional Mohun Biswas.

|