|

|

|

|

June 2018

|

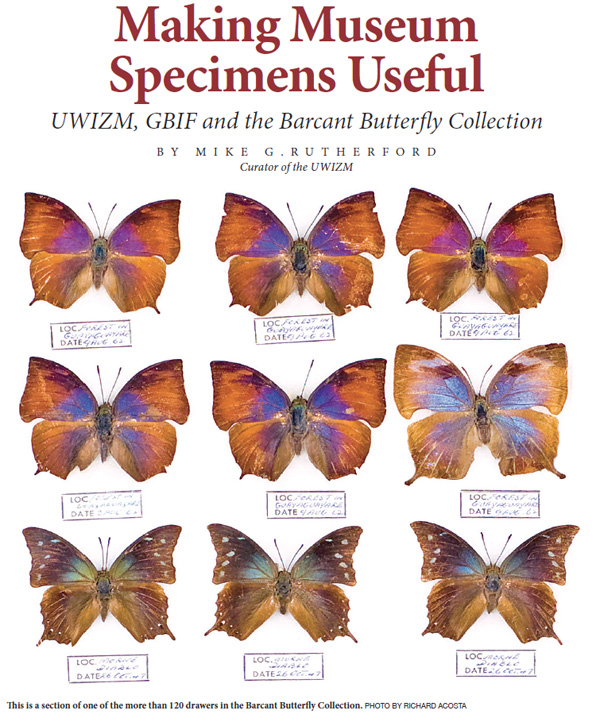

For example, if a researcher from the U.K. is studying a particular species of butterfly that is only found in Trinidad and they want to know which museums have specimens, it could take them a long time to track down every relevant museum collection. They might have to visit many collections all over the world, or these days, search through online records (if available!), then contact curators who would then have to go through their collections and find the correct specimen and then pass that information back to the researcher. All this could take months of work. It would be much easier if there were a single source of easily accessible online information that covered all museum collections and other species occurrence records. Fortunately there is - the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF for short). Last year the University of the West Indies Zoology Museum (UWIZM) partnered with the National Zoological Collection of Suriname and the Barbados Museum and Historical Society in a project titled Improving biodiversity data accessibility in the Caribbean countries of Trinidad & Tobago, Barbados and Suriname. This project was funded by the European Union through the GBIF - Biodiversity Information for Development (BID) programme. The purpose of the project is to upload the biological records currently housed in these museum collections onto the GBIF platform and to encourage and help other collections in the region to share their data as well. The funding given to the UWIZM was used to employ a database assistant responsible for converting and uploading the museum records. These records are then publicly available for anyone to search – you can have a look for a particular species or study a certain place and see what has been found there in the past. As of May 2018, the GBIF site has over 981,500,000 occurrence records from more than 1,100 institutions worldwide and these numbers are growing all the time. As well as uploading the UWIZMs records, we will also be sharing species records from other collections. Some of these are physically housed in the UWIZM, such as the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI), Caribbean Epidemiology Centre (CAREC) and the National Museum of Trinidad & Tobago zoological collections, but there are other zoological collections in Trinidad such as the Barcant Butterfly Collection (BBC) at the House of Angostura Museum. This well-known collection of thousands of preserved butterflies was bought by Angostura in 1974 from the collector Malcolm Barcant and has been a prized possession ever since. The BBC is overseen by Giselle Laronde-West, Senior Manager of Hospitality and Communications, and Ronda Betancourt, Public Relations Officer. Although they have done a great job of displaying and promoting the BBC, they don’t have the zoological experience to make the most of the data, so a few years ago they invited the UWIZM to help catalogue the butterflies. The collection information associated with each butterfly is carefully placed next to each specimen in a label and is also contained in Barcant’s book Butterflies of Trinidad And Tobago. Unfortunately this book is out of print and copies are rare, so sharing the data online is the best way to make it accessible. Pauline Geerah, an on-the-job trainee attached to the UWIZM for two years, and I collated previously taken photographs of the butterflies and then Pauline spent much of her time transcribing the collection data from the thousands of tiny hand-written labels into a spreadsheet. This was then uploaded to the UWIZM’s database along with a photo of each specimen. Renoir Auguste, the GBIF database assistant, then took these records and transformed the data into the correct format for uploading to GBIF. This involved adding geographic coordinates for each record and making sure that the species names were the most up-to-date available. Once the more than 4,000 records were ready, they were uploaded and are now accessible to anyone with access to a computer, making them truly useful. To see the butterfly records, visit www.gbif.org, click on Datasets and search for Barcant Butterfly Collection (the collection has been split into six family groups). You can zoom in on the map of Trinidad & Tobago to see what species were found where or look through the lists to discover rare and common butterflies. To see the butterflies themselves you’ll need to arrange a tour of the House of Angostura. Visit www.angostura.com/tours/ for more information. Finally, if you would like to visit the UWI Zoology Museum to see thousands of other animals specimens, come to The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine campus from Monday to Friday between 9am and 4pm and ring the doorbell or email uwizoologymuseum@sta.uwi.edu or mike.rutherford@sta.uwi.edu to arrange a date and time. |

How do you make a museum specimen useful? Putting it on display and letting visitors come and look would probably be the most common answer. Although it’s true that this helps with education and hopefully inspires a love of nature, the scientific usefulness is still lacking. A good scientific specimen is one which has lots of information: what species it is, where and when it was collected, who collected it along with any other details. However, it only really becomes a useful specimen when that information is easily accessible.

How do you make a museum specimen useful? Putting it on display and letting visitors come and look would probably be the most common answer. Although it’s true that this helps with education and hopefully inspires a love of nature, the scientific usefulness is still lacking. A good scientific specimen is one which has lots of information: what species it is, where and when it was collected, who collected it along with any other details. However, it only really becomes a useful specimen when that information is easily accessible.