Growing up in the 1950s and 60s, in her grandmother’s kitchen in Reform Village, Gasparillo, Dr Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted learned that nutritious food made you strong and smart. This lesson, translated into a philosophy of “nourishing, not feeding”, governed her work throughout her 50-year career as a nutrition scientist, and lies at the heart of the research, innovations and life-changing impact that made Dr Thilsted the 2021 World Food Prize Laureate.

The World Food Prize is an international award recognising individuals who have made significant contributions to the quality, quantity and ease of access to food worldwide. Awarded annually since its launch in 1987, the prize highlights the importance of a having sustainable food supply for every human being.

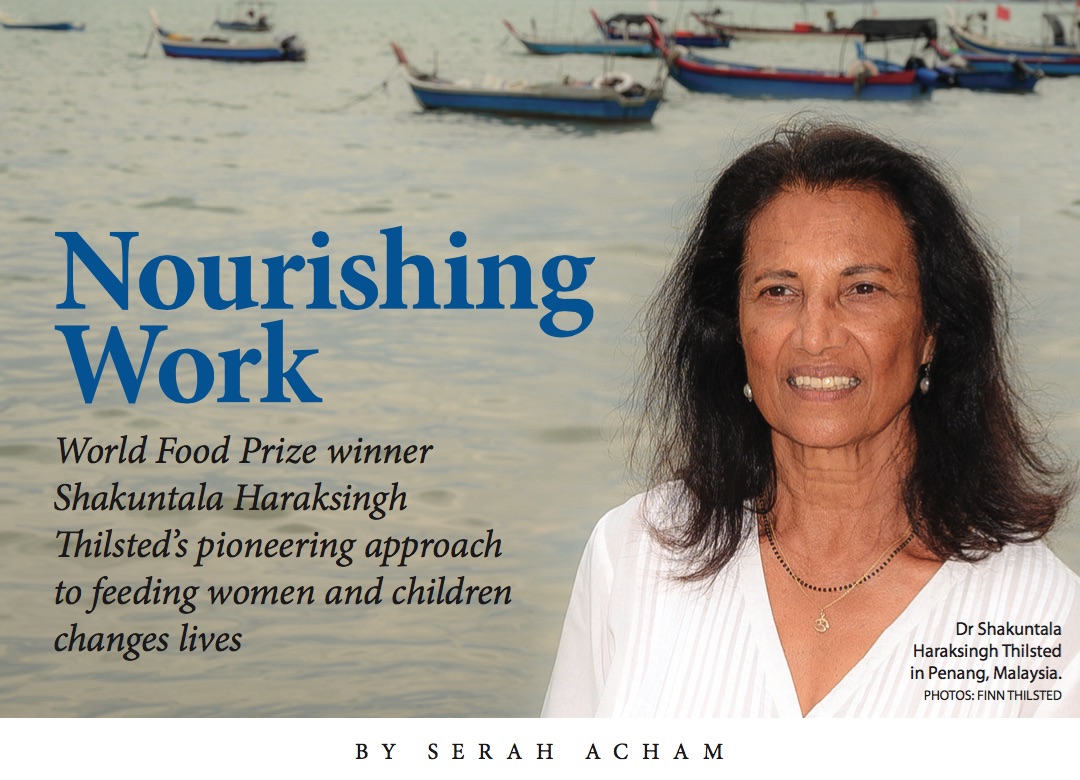

Dr Thilsted, Global Lead for Nutrition and Public Health at WorldFish in Penang, Malaysia, was awarded this year’s prize for her pioneering work on fish-based food systems to provide nourishment for, and prevent malnutrition of, children and mothers in poor communities in Asia and Africa.

She was raised in a home where eating nutritious food, pursuing a good education, and sharing the benefits of one’s hard work with others were encouraged and expected.

“The village of our childhood was marked by a noticeable sense of fictive kinship which nurtured a feeling of obligation to help friends and neighbours whenever possible,” says Dr Kusha Haraksingh, Honorary Consultant at The UWI’s Office of the Vice Chancellery and Dr Thilsted’s brother.

Dr Haraksingh, a historian, educator, and attorney, recalls that, “Growing up, my sister Shakuntala exhibited a strong sense of determination and personal resourcefulness, and a compulsion not to leave anything undone. She developed formidable organisational skills, so much so that we occasionally called her ‘the manager.’”

After attending Naparima Girls’ High School, where she developed a love for science and mathematics, Dr Thilsted enrolled in UWI’s Tropical Agriculture programme at the Faculty of Agriculture. Here, she learned about producing nutritious food through animal production and how the body uses the nutrients it absorbs from food.

In 1971, Dr Thilsted graduated from the UWI St Augustine Campus with her bachelor’s degree. She began both her career and her life’s theme of making strides within and for a developing society as the first and only female agricultural officer in the Tobago Ministry of Agriculture, Lands and Fisheries. Two years later, she returned to Trinidad and took on her first research-centred job at The UWI’s Faculty of Natural Sciences.

Dr Thilsted married and moved to Denmark with her husband in 1974. She earned her PhD as a Veterinary Faculty for Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Fellow at Denmark’s Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, in 1980. Her research was on the metabolism of nutrients in cows to improve milk production.

Over the following years, she taught and researched at the University of Dar es Salaam and the Sokoine University in Tanzania as an FAO Associate Expert; and then as the Associate Head – and later Head – of the Department of Animal Physiology at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University in Denmark.

In December 1986, Dr Thilsted and her family moved to Bangladesh, where her husband, a Danish diplomat, was posted and where her research into aquatic foods and malnutrition prevention began.

“We were extremely privileged with the education we got, the jobs we had, and we knew that we could give back and, at the same time, have a good life for ourselves,” she says, so “we only wanted to be posted in developing countries”.

They lived in Dhaka and she worked at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research as a nutrition coordinator in its Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit. The centre treated more than 6,000 malnourished children each year. Part of her role was visiting the slums and peri-urban slums in Dhaka to identify malnourished children and recommend them for treatment and home rations provided by the World Food Programme.

Believing that the solution lies in prevention, and feeling “instinctively concerned” as the mother of two young children at the time, she wanted to develop “solutions that could keep women and young children well nourished” using nutritious foods that were easily available and acceptable within the culture.

“I was very intrigued about the way people treated food in Bangladesh,” she says. She was curious about the commonly recited proverb “Mach-e bhaat-e Bangalee”, meaning “fish and rice make a Bengali”. Why was fish first when “rice is the staple food”?

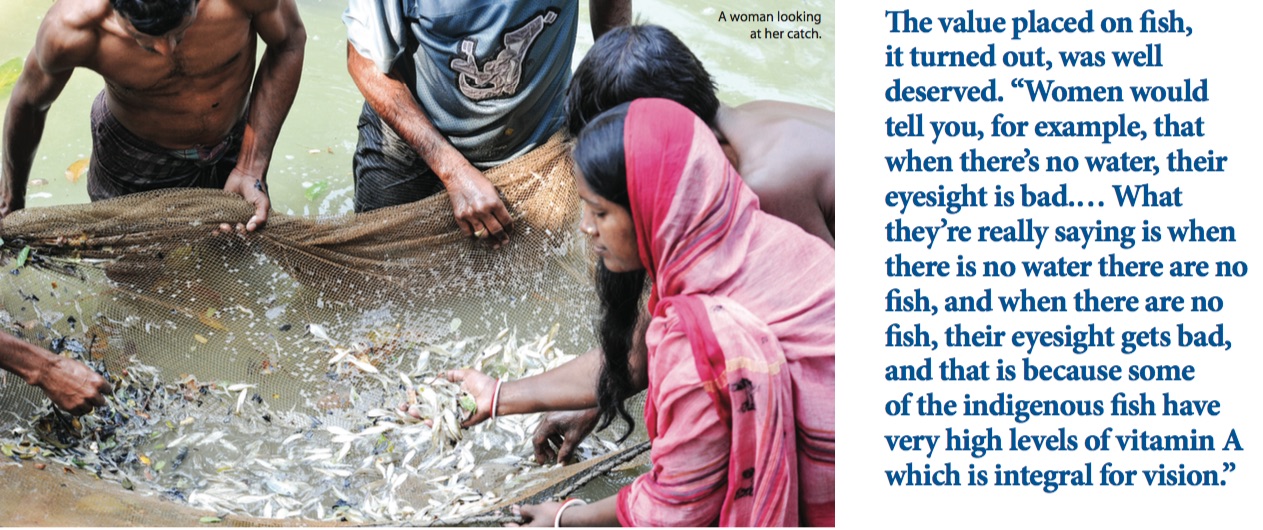

The value placed on fish, it turned out, was well deserved. “Women would tell you, for example, that when there’s no water, their eyesight is bad.… What they’re really saying is when there is no water there are no fish, and when there are no fish, their eyesight gets bad, and that is because some of the indigenous fish have very high levels of vitamin A which is integral for vision.”

Dr Thilsted spent five years in Bangladesh, during which she championed the nourishment of children and mothers – leading the development of the rehabilitation unit, advocating for breastfeeding as a member of two UNICEF committees, and playing fundamental roles in projects organised by UNICEF and national nutrition councils. She also continued gathering insight into the fish that formed such a vital role in the diets of the people she served.

She took this information with her when she returned to Denmark in 1991. Back at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, she assembled a team of colleagues and students, and began researching the nutritional composition of Bangladesh’s traditional foods.

“Then I zoned in on fish and the small indigenous fish in Bangladesh,” she says, finding that “these small fish species were extremely rich in multiple micronutrients, vitamin A, vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium and essential fatty acids… [they] had the potential for nourishing people and could be considered a super food.”

Armed with this breakthrough, Dr Thilsted set out to increase small fish consumption, particularly by women and children in vulnerable communities. She provided the people in poor communities throughout Asia and Africa with innovative means of nourishing themselves while preserving the environment. By adapting and developing fishing and farming methods, creating fish-based food products, spearheading curriculum development and capacity-building at universities and national research institutions, and influencing policy at the government level, Dr Thilsted increased production, productivity and incomes, involved and empowered women, reduced waste and changed lives over the decades.

Her emphasis on “nutrition-sensitive approaches,” – that is, quality of food over quantity – was a novel concept when she began her work, and still is, she says:

“There was a lot of focus on the staple food crops like rice, wheat and maize, and… on ensuring that people did not go hungry, so much of the focus is on quantity.”

But she was interested in “foods that complement the staple foods on the plate, [like] fish and other aquatic foods...I was moving the narrative from just feeding to nourishing.”

The idea of nourishing minds and bodies, rather than simply feeding them, is fundamental, she says. And her focus on young children and their mothers has far-reaching implications – a well-nourished mother gives birth to a well-nourished child who does well at school and grows into an adult who performs well at work.

She explains that the first thousand days of a child’s life, from conception to their second birthday, are critical because “that’s when you have the fastest rates of growth and development,” particularly brain development and cognition. “You set the foundation for the rest of the child’s life,” she says, and the child’s success is “good for national development [and] global development.”

On May 11, Dr Thilsted was awarded this year’s World Food Prize for her ground-breaking work and its incredible impact. In the same way she began her career with a first in 1971, she is accepting this award as the first person from the Caribbean, and the first woman of Asian heritage, to gain this recognition.

She’s humbled and knows this award gives her a powerful platform. She hopes to use it to encourage governments and the international community to heed “this message of ‘not just feeding, but nourishing’ [and] I hope it inspires young people to work in this area”.