For the month of May, nurse Jane (name changed) worked a staggering amount of extra shifts at the Couva Hospital and Multi-Training Facility, where she provides care for COVID-19 positive patients.

As Trinidad and Tobago began experiencing a surge in positive cases starting in mid-April, Jane was one of many medical staff transferred from the Arima General Hospital to the Couva Hospital in late April to assist with the influx of patients.

“My first day was a big shock and I won’t ever forget it because of the vast amount of patients we had compared to the nursing staff. There was no way you could’ve put what you learned in school or at another hospital into practice right there and then because the nurse to patient ratio was too much,” shared Jane, a graduate of The UWI St Augustine School of Nursing (USoN) at the Faculty of Medical Sciences (FMS).

Jane described an ever-increasing workload as staff themselves went into quarantine or were hesitant to pick up extra shifts due to fear of prolonged exposure.

“I am tired. That’s the only way to sum it up. It’s very difficult and stressful. A lot of people don’t do the extra duties because you put yourself at risk of infection more than the allotted time and it puts your family at risk as well, especially if you’re the only essential worker at home,” she said.

'You have to counsel patients, to show sympathy, show empathy, and make sure that not only are their physical needs met, but their emotional needs as well… You have to make sure you put a smile on that patient’s face'

While Jane, like other health care workers, may be experiencing burnout, she says that she continues to put on a strong face for patients and has even changed her approach to nursing.

“Our way of care and reacting to a patient has changed because there are patients who are in Couva for months who haven’t seen the outside world. You need to think about the psychological effect of it. You have to counsel patients, to show sympathy, show empathy, and make sure that not only are their physical needs met, but their emotional needs as well. Even if you’re having a bad day coming to work, that bad day has to quickly turn into a good day. You have to make sure you put a smile on that patient’s face so they know that there are people rooting for them even though their families are not there,” Jane explained.

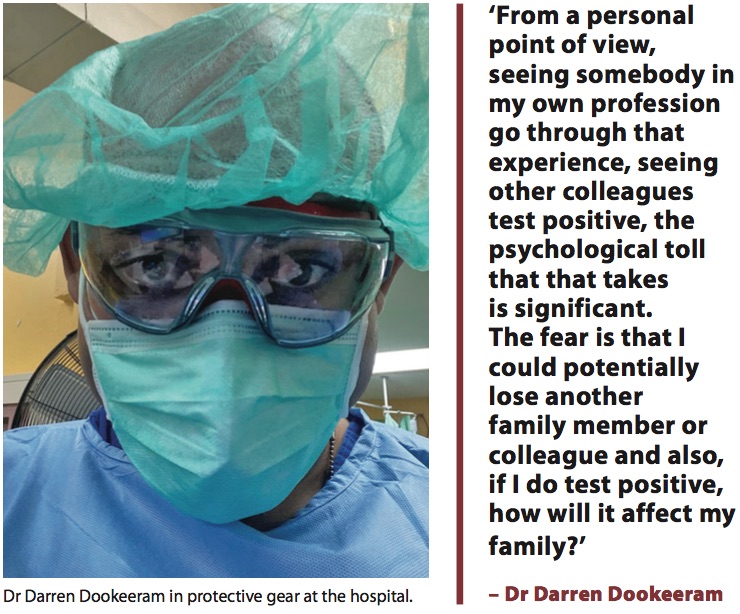

According to Dr Darren Dookeeram, the psychological burnout wasn’t experienced by COVID positive patients and their care providers alone, but by all healthcare workers nationwide:

“The hospitals were required to run regardless of the pandemic, so Accident and Emergency had to function. People were still coming with chest pains and after car accidents and so on. There were two very distinct elements that were unfolding at the same time. At the peak of this, it was very difficult because of the sheer number of people. Patients who tested positive do require isolation and it was very easy for the existing infrastructure to be exhausted, not necessarily as a marker of the pitfalls of the system, but a marker of the severity of the disease.”

He added that, “Everybody is exhausted and stretched to their limits, not just in my department, but the entire hospital and all levels of staff. The personal sacrifice can never be quantified. I’m not just speaking about myself, but what I have seen the hospital system being asked to do in the last year has been just great personal risk.”

Dookeeram is a specialist emergency physician stationed at the Sangre Grande Hospital, former head of the Trinidad and Tobago Medical Association (T&TMA) and a graduate of the School of Medicine at FMS.

He noted, however, that organisations such as the T&TMA have implemented some measures to provide mental health services to medical staff, which even he has used.

Part of the reason that the psychological effects of treating patients are heightened is the isolation necessitated by the nature of the virus. This became all too evident when Dookeeram lost a younger cousin, who was also a physician, to the virus in mid-May.

“It was traumatic on multiple levels. The inability to share that experience was one thing, but then for me I’m wondering: Is my uncle infected? How does the funeral unfold? How does this affect the rest of the family? It goes a lot deeper than just a personal tragedy because of the lack of closure that people experience when somebody passes because it deprives you of the grieving experience,” he said.

“In a normal Trinidadian sense of someone being ill and the entire neighborhood showing up to share in the experience, that’s definitely not on the cards with COVID,” he continued. “It was very difficult for us and for a lot of families that we had to speak to.”

The death increased his paranoia and anxiety. As a parent and husband with a wife who is also a healthcare worker, Dookeeram had to be mindful of his every movement.

“From a personal point of view, seeing somebody in my own profession go through that experience, seeing other colleagues test positive, the psychological toll that that takes is significant. The fear is that I could potentially lose another family member or colleague and also, if I do test positive, how will it affect my family?”

In early June, T&T had an average of 401 new positive cases per day. The death toll on June 10, according to Ministry of Health data, was 610 – an increase of over 400 from the end of April. The picture painted is grim, but there are two hopeful developments: the introduction of local genome sequencing and mass vaccination.

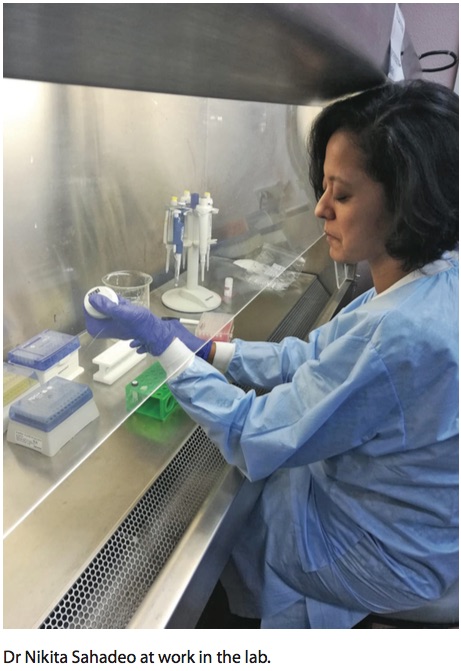

The UWI St Augustine Faculty of Medical Sciences (FMS) has been at the forefront of the introduction of whole genome sequencing locally through a project with the Ministry of Health and the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA). A team of researchers was assembled in December, 2020 for the “COVID-19: Infectious Disease Molecular Epidemiology for Pathogen Control and Tracking (IMPACT)” project.

Genome sequencing analyses the DNA of virus samples to identify variants as well as provide surveillance data such as the date and introduction of a virus into a community or country, and patterns of spread. Sequencing is the only way new variants can be detected.

Dr Nikita Sahadeo, a post-doctoral researcher in Molecular Genetics and Virology attached to the Pre-Clinical Sciences department, generated all of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes (now over 800) as part of the IMPACT project. Sahadeo believes that the project is extremely important because it provides data in real time that is actionable and informs public health policies.

“We have a couple of things that we wanted to accomplish with this project. The first is we wanted to establish capacity at the Faculty of Medical Sciences to do whole virus genome sequencing where we would be able to do the sequencing ourselves as opposed to sending it away or to collaborators, and that’s certainly something we’ve been able to do so far,” she said.

“And second,” Sahadeo continued, “with viruses, the actual genomes themselves contain so much information that we can look at the information that’s contained in them and look into outbreak dynamics, viral transmission patterns, the different types of lineages and viral histories.”

The IMPACT team has been able to identify 16 variants of the virus locally. The most prevalent variant is the P1 or Brazilian variant, which currently accounts for 38 percent of our sequences generated and is at the community spread stage. The P1 variant has been deemed a “variant of concern” because it spreads more easily and is somewhat resistant to certain treatments. The data is still being analysed, however, according to Sahadeo, and no conclusions can be made just yet.

“What we’re doing will still be important once we’ve moved past COVID. I don’t think the technology and the system and capacity will stop being relevant because it’s adaptable to any virus and I think the technology will create opportunities for more research,” she noted.

And as the government proceeds with mass vaccination drives, genome sequencing will be able to assess the effectiveness of vaccines.

Dookeeram sees vaccination as key to ending the pandemic and controlling the current surge. He said there are many examples of trends of decline in infection and death rates internationally after vaccines were introduced. “I think there is that light at the end of this very dark tunnel and I think we could get to that light a little faster if people would put aside their fears and get their vaccines, and, in the interim, really pay attention to the public health ordinances,” he said.

For nurse Jane, it’s not easy to share his sentiments. She witnesses people disobeying the public health ordinances on a daily basis, and from her point of view at Couva Hospital, finding hope is difficult. “Things are just getting progressively worse,” she said.

Sahadeo, whose dissertation focused on the evolution of the dengue and chikungunya viruses in the Caribbean, said that although working on the project during the pandemic has been stressful, she sees a bright side.

“It’s sad about the situation that we’re in, but I am happy that with the skills I’ve developed, I am able to put them to use. It’s nice to see something tangible come from the work that I’m doing,” she said.