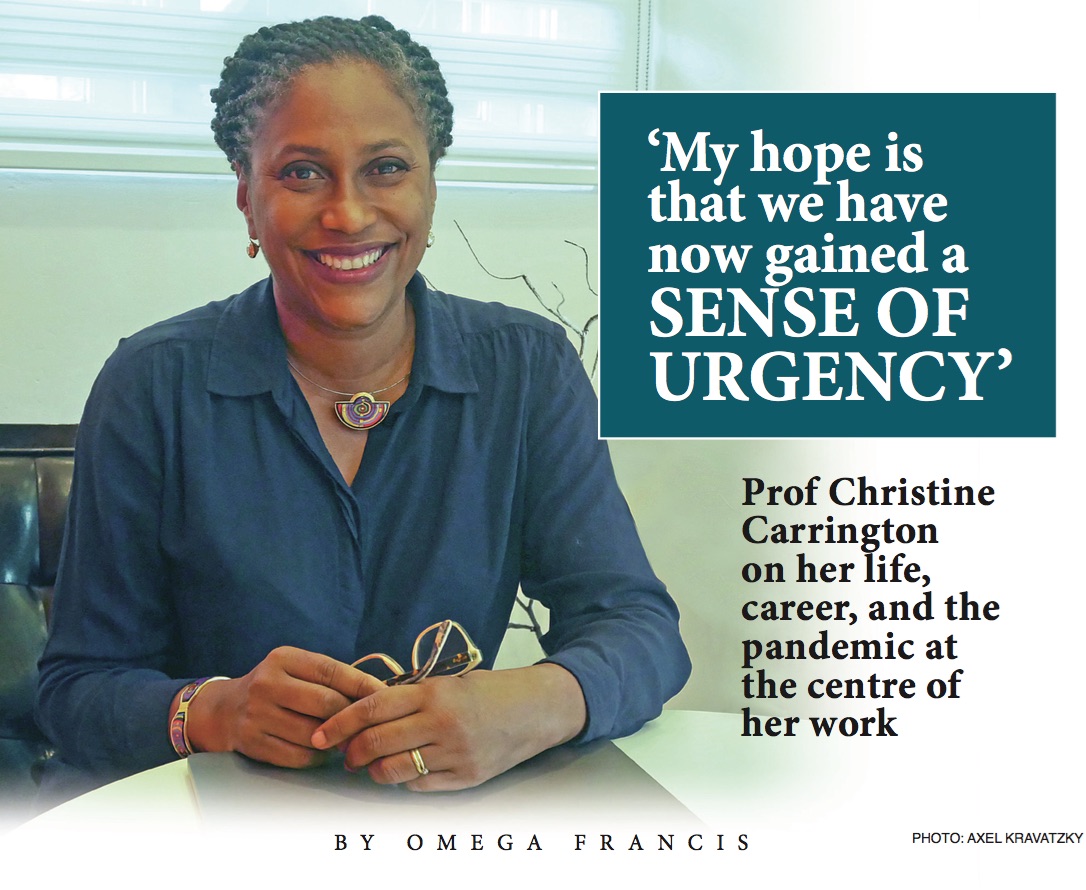

Christine Carrington, Professor of Molecular Genetics and Virology at The UWI, has spent 30 years studying viruses, focusing primarily in the past 20 years on the genomics and evolution of so-called “emerging viruses”. In particular, she and her team investigate how evolutionary changes in viruses and changes in the environment influence viral emergence, patterns of spread, and epidemic behaviour.

These days, however, she has been spending her days heavily involved in the local public health efforts of The UWI COVID-19 Task Force with her research team and fellow virologists at the Faculty of Medical Sciences. UWI TODAY sat down with the professor recently and had a chat about viruses, her life and motivations, and what she sees as the path to emerge from this pandemic.

UT: Has being a virologist prepared you for the pandemic, or did you have to make significant changes?

CC: Understanding viruses, I suppose I was better prepared than most to accept the interventions that were required to limit the spread of the virus. Because of my background, I am also better able to discern sense from nonsense on social media and other platforms, so I was less panicked than others. I certainly wasn’t prepared for working remotely, online teaching, and having two children at home doing online school but as a virologist, I was not at all surprised that a virus with pandemic potential had emerged from an animal population.

We’ve had HIV, Ebola, SARS, MERS, H1N1 influenza, chikungunya, and Zika. Virologists have been saying for years that this would happen because of human activity and our impact on the environment (habitat destruction, urbanisation, agricultural practices, the wildlife trade, and rapid global travel).

UT: What does it mean to be a virologist, and how has your work as a virologist impacted Trinidad and Tobago and the Caribbean?

Being a virologist is about studying and understanding viruses. I love viruses and really do find them fascinating. I certainly don’t enjoy what some of them do to the people and the other organisms they infect, but I can’t deny that I enjoy studying them. Because of the research work my fellow virologists Professor Christopher Oura, Dr Jerome Foster, and I have done at UWI over the years, when COVID-19 hit, we had a group of well-trained and experienced technicians, current and former PhD students, who were immediately available to step into the breach. They already had the practical skills and background knowledge required, and several of them were involved in training Ministry of Health laboratory workers and volunteered in the COVID-19 diagnostic lab.

Since December 2020, my lab has been carrying out genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern on behalf of the Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Health, and 17 other Caribbean countries through the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA). The work arose from a research project I lead, called the COVID-19: Infectious disease Molecular Epidemiology for PAthogen Control and Tracking (COVID-19 IMPACT). It’s a UWI-led collaboration involving the Ministry of Health, CARPHA, and collaborators from the universities of London and Oxford.

The main goal of the project was to establish local capacity for rapid whole genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in order that viral genomics and related molecular epidemiological approaches might be incorporated into local and regional public health efforts. The project was conceived since May 2020 and after a wait for funding (which we got from the T&T UWI Research and Development Impact Fund), the postdoc on the project, Dr Nikita Sahadeo generated the project’s first SARS-CoV-2 genomes in early December 2020. Just in the nick of time, because the first variants of concern emerged very shortly after that.

We’ve identified variants of concern and variants of interest in several Caribbean countries, just as we detected P1 in T&T. Also, the genome sequence data generated by the project is uploaded onto a public database called GISAID, so that the global scientific community can access and incorporate them into COVID-19 research efforts.

The original COVID-19 IMPACT project was not designed or manned to provide routine surveillance on the scale required since the emergence of the variants, so I’m really very grateful to Nikita and [Senior Research Technician] Vernie Ramkissoon for going above and beyond in the lab; with support coming from the Ministry of Health, CARPHA and PAHO, they are getting some relief.

UT: What made you want to become a virologist? What has been your motivation?

CC: I’ve always enjoyed the sciences and biology in particular. My mother was a biology teacher at St Augustine Girl’s High School and she taught me when I was there. She was an excellent teacher, so that helped. My father is not a scientist (his areas are linguistics and education) but he always enjoyed science and technology. Intellectual curiosity was always nurtured in our house. Questions never went unanswered. If no one knew the answer, my father would drag out an encyclopaedia or contact someone who might have an answer or help guide us to it.

My interest in biology was also influenced by nature programmes and books by David Attenborough, Gerald Durrell, and James Herriot. In sixth form biology, we studied viruses and I was hooked. I was first attracted to them because they reminded me of the invading aliens in the Sci-Fi books I used to enjoy. During my BSc degree programme in Biotechnology at King’s College, University of London, we had one virology course which I really enjoyed. That was enough to convince me to pursue a PhD in Molecular Virology at the Institute of Cancer Research (also University of London).

UT: People know you primarily as a virologist and academic, but what about when you are not in a lab coat?

CC: Outside of science and academia, most of my time is spent with family and friends. My hobby is being around people I like! Being around people I like, with good food and drink, in a beautiful setting or in a foreign country… even better.

UT: What’s your family life like? Do you have kids? Are they scientists in training?

CC: My husband Axel and I have been together for 32 years and married for 27. We met while at the University of London. He was at the London School of Economics and I was at King’s College but we lived in the same hall of residence. We have two children: Lukas who is 16, and Mia who is 12. Combining work and parenting has been no easy task but I think we make a good team. We aren’t training or pushing the children to have careers in science but we try to ensure that they can think scientifically and that they are at ease with the sciences. Both of them have a healthy curiosity about the world and how it works.

UT: Is your husband a scientist as well?

CC: Well, he would like to think so! His PhD is in Development Studies and Operations Research, and before that he did economics and philosophy, so his background is in the social sciences and he likes to remind me that the word “science” is in there. He works as an organisational consultant specialising in corporate governance, leadership, and strategy. He is very passionate about purpose-driven businesses and organisations that systematically create profitable solutions for both people and the planet, as opposed to those that profit for the sake of profit, or profit from creating harm. I know… he’s a nice guy, so I forgive him for not being a “real” scientist.

UT: Why, after seeing a drop in COVID-19 cases two months ago, are we now experiencing such a huge surge in cases? Is this the second wave we have been warned about?

CC: This has been the experience all over the world. SARS-CoV-2 spread primarily through close human interactions. Countries restrict human interactions to combat the spread of the virus and then when reported cases are low, they relax restrictions so the economy can restart. Once the level of interaction increases, any virus that is still present or newly introduced, can then precipitate a second wave. Some of the new variants that have emerged are more transmissible than previously circulating lineages which together with other factors may contribute to rapid resurgence.

UT: When it comes to pandemics, do they all follow a similar pattern (first and second wave and variants)?

CC: Whether you have successive waves of infection and the length of times between waves depends on the type of virus, how it is transmitted, how quickly the virus evolves, the nature of the immune response to it, and also on the extent of public health interventions. Influenza virus, like SARS-CoV-2, is a respiratory virus and, almost every year, new variants of influenza virus emerge. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, a similar pattern of waves of infection was observed. There were four major waves over two years. In contrast, with the HIV pandemic, there was a steady increase in new cases over many years before there was a decline. So it differs from one virus to another.

UT: What are the current expectations of the uptake of the vaccines on the spread of COVID-19 and what does the future hold when it comes to pandemics (new and old)?

CC: I’m optimistic that Trinbagonians will accept the vaccines in large enough numbers to provide a level of population immunity that will allow us to get back to a more normal life. The vaccines are safe and effective at preventing severe disease, hospitalisation, and death. There is evidence of this from several countries. The people dying or in hospital with COVID-19 are the unvaccinated.

As for the future, this certainly won’t be the last virus with pandemic potential to emerge. The conditions that precipitated the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, and all the other viruses that emerged before it, remain in place. My hope is that we have now gained a sense of urgency about addressing those conditions and that we have learned enough from the current pandemic to allow us to respond much more quickly and effectively to prevent another. The rate at which scientists were able to produce COVID-19 vaccines augers well for the future, but we still need to address the issue of equity when it comes to vaccine distribution.

UT: Once, while watching a livestream of your presentation during a national briefing on COVID-19, someone in the chat said “I want my daughter to grow up to be a scientist just like Prof Carrington”. What are your thoughts on women and girls in science, and do you strive to be a model for them to follow?

CC: That’s very flattering. I’ve had some truly inspiring role models and mentors, so I know how important it is. Things like gender and race shouldn’t play a role in people’s career aspirations but the reality is that barriers exist – some are imposed on us and others we impose on ourselves. I really don’t set out to be a role model for anyone or any specific group. I just try to be a good scientist and a good person. If in doing that I help to lower or remove barriers, or inspire people to climb over them, then all the more reason for me to continue trying to do my best.