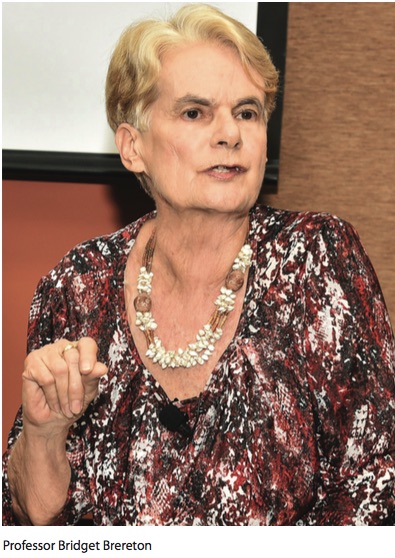

Professor Brereton brings a lively take on our past

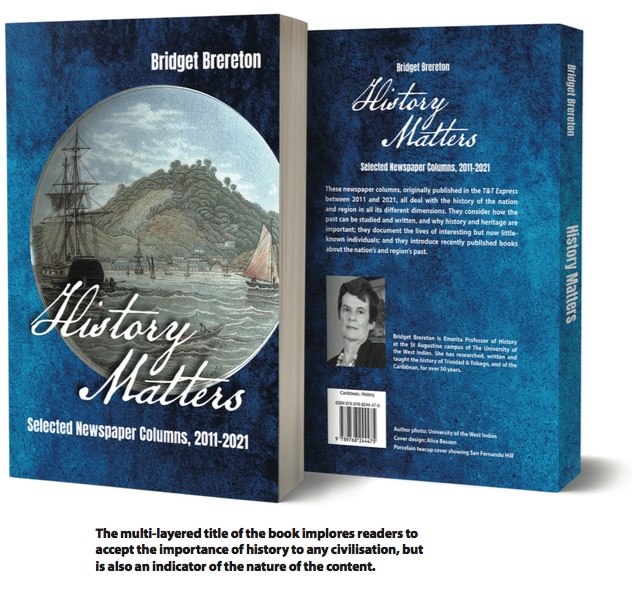

A cookbook here, a couple memoirs there; a church, a mandir, a mosque; academics, pioneers, rebels; villains, scoundrels and heroes - don’t be misguided by the truthful title of Bridget Brereton’s new book, History Matters, - the range of subjects is as broad as it is entertaining.

Professor Brereton, the noted Caribbean historian who has retired from The UWI where she held many distinguished posts, including Acting Principal of the St Augustine Campus, has published a collection of her Express newspaper columns from 2011 to 2021. Within those ten years, she had written 248 of them, from which she selected 138 for the compilation, a process she described as “painful,” but necessary as “I didn’t want an off-putting tome”.

It might have turned out to be a tome otherwise, but it could never have been off-putting, because Prof Brereton’s writing style is engaging and conversational. She maintains academic rigour, but has the rare quality (especially among academics) of being able to create interesting stories about events and people.

The multi-layered title of the book implores readers to accept the importance of history to any civilisation, but is also an indicator of the nature of the content.

She brings her expert historical perspective to the material and, thankfully, has corrected misinformation that often carelessly appears in print and then goes on to be accepted as historical fact. She responds directly to some individual inaccuracies, and to others in a more general manner. For instance, “We sometimes assume that Islam was first brought to Trinidad and the Caribbean by the Indians who began to arrive after the end of slavery. But, in fact, the faith first arrived here much earlier, brought by the enslaved people from those areas of northern West Africa which had been Islamic for centuries. And Trinidad’s Mandingo people were Muslims.”

The columns varied in length, based on word counts set by the newspaper, so they are fairly short, but given today’s environment, where reading is confined to three-minute forays, this is one of the collection’s strengths.

The book has been divided into six sections, all coming under the heading of history. One: Ideas, Debates, Narratives; Two: Anniversaries, Celebrations, Holidays; Three: Approaches, Sources, Heritage; Four: Events and Developments; Five: People; and Six: Books and More Books.

The last is the longest—deservedly so because, over the years, Brereton had been the most consistent voice “noticing” the arrival of new books, and alerting readers to their content and quality.

In the course of reading the columns, it struck me this was an excellent way to broaden the range of information for young people who are growing in an educational environment that sequesters them from real knowledge of the societies they inhabit.

History matters; but not every student and not many adults, have been exposed to the diverse stories that tell about our past in ways that they can relate to. What you learn comes from texts that adhere rigidly to a specific discipline as outlined in a syllabus, no digressions allowed.

In this context, the book should be required reading in schools, from primary level upwards. It is an intelligent way to educate our children about themselves and their Caribbean. What a wonderful chance for them to learn about their heritage, and what an excellent portal for them to enter a world where they can take pride in their people and their place.

In one piece from October 2019, “School histories,” she focused on how the history of our various schools was an important aspect of the overall history of communities and groups. Noting that the older secondary schools had fairly well-documented histories (QRC, St Mary’s College and the ‘Convents’), she lamented that this is not the case for others.

“They have a long past, being founded in the 1800s, and their alumni have always included people from influential and prosperous families. But this is not enough.”

She goes on to propose that all schools be so covered, and that the research and writing could be “a project ideally suited to secondary school students (SBAs at CSEC and CAPE), and university undergraduates who undertake research papers as part of their degree studies”.

It is a marvellous suggestion, one which the Ministry of Education should consider implementing.

In fact, as the alarming state of affairs regarding student violence runs parallel with the savagery outside school gates, it is particularly important to address the roots of this national collapse. Many feel alienated from their societies, excluded and disrespected, and lack self-esteem. Adrift without the mooring of feeling connected to this place they cannot call home, they rage against institutions and systems that have failed them. If they were to become involved in ferreting out the histories of their families, schools, and communities, it might engender a sense of belonging—and you wouldn’t want to hurt something you belong to, would you?

What has been evident in the midst of the upheaval wrought by an unprecedented pandemic is that the old ways of doing things have to be recalibrated.

It is not a simple matter of introducing civic studies into curricula—in the old days there were social studies classes at primary school—it requires rethinking the way material is made available to citizens at all levels.

Professor Ken Ramchand has published his collection, Matters Arising, 45 pieces from 1987 to 2020, the title coming from his newspaper columns of the time. The late Professor Selwyn Ryan had been one of the most prolific columnists, but while his published works include much material from those writings, there is no book devoted to reproductions of his articles.

Collections like these, compiled from articles that originated in newspaper columns—accessible, interesting, diverse, and topical—have a significant role to play in lifting our collective consciousness about who we are, where we have been, and what is possible.

Brereton’s book is interesting from end to end, but it also fulfills her intent “to contribute to public education on T&T’s and the region’s past”. It is an invaluable contribution.