|

|

|

|

March 2010

|

War of words: Haiti’s battle over languageBy Professor Valerie Youssef

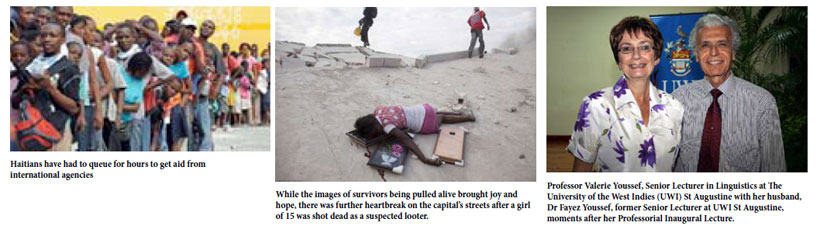

Masked in the initial coverage of the relief effort, but surfacing some ten days later as I wrote the lecture, was the difficulty of delivering aid to a devastated society, that, even before the disaster, had little infrastructure to sustain it. Off the world media radar for some years, and distorted in its image by constant association with violence, Haiti had had no way of transmitting its real internal situation, on which light was now shone. Important as it was to bring immediate relief, the issues of Haiti’s long term sustainable development needed redress now more than ever. Suddenly policy suggestions made ten years earlier took on renewed significance. It was in this context that I set out to write. Historically, Haiti’s succession from Spanish to French control resembles Trinidad’s. From Columbus’ invasion in 1492 there were few slaves under the Spanish, but major decimation of the Amerindian population; then from 1697, a sugar economy was built up with slaves brought from Congo, Guinea and Dahomey (now Benin). The Haitian language developed as the slaves needed a common interactional mode and this new code was realized out of contact among regional French varieties and Niger-Congo languages including most saliently, Kwa and Bantu languages. When Haiti became the first black independent nation in 1804, it established a law that any escaped slave who arrived there could become a Haitian and hence free; it thereafter served as a haven for slaves fleeing Jamaica and other territories. The Caribbean’s own modern-day rejection of Haitians fleeing their circumstances, is further reason for the region to examine its position vis-à-vis Haiti today. Sadly, the country was decimated internally by oppressive leaders from that time on. Foreign influence, in particular from the USA, has characterized the twentieth century, and has been heinous in its self-serving force. Internally, the reign of the Duvalier family from 1957 until 1986 was the most exploitative, first under Francois Duvalier, and then under his son, Jean-Claude. The economy was subverted to both Duvalier and US interests, such that grossly underpaid factory labour became the mainstay of the masses and peasant agricultural production was systematically undermined. In that period, Haitians report that anyone involved in helping others to acquire literacy or education was arrested. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the people’s great hope, came to power in 1990, but was ousted seven months later, and in the three-year period of suppression which followed, extreme brutality was meted out to the population. When he returned with American support in 2000, his capacity to change circumstances for the masses was never actualized. Aristide ultimately proved ineffectual and was violently ousted from power in 2004. Haitians had believed that he would rule them justly and their disappointment was concomitantly more profound. René Préval, Aristide’s former protégé, has been President since 2006, supported by UN peace-keeping forces. Haiti remains a country where 56% of the population still lives on less than $1 per day. So what of language in all this? Haiti has a population of 8.5M, all of whom are Kreyòl speakers. Outside Haiti there are another 4M. Kreyòl is modern Haiti’s national language and one of two constitutionally-recognized official languages, the other being French. Despite this, most official documents are written exclusively in French which is spoken by only one-fifth of the population. The Haitian birth certificate, for example, exists only in French. Such French-only policies create a situation of “linguistic apartheid” which goes against the spirit of Article 5 of the Constitution which states that “all Haitians are united by a common language: [Haitian] Creole”. The particular problem which Pierre Vernet was concerned to solve was that of creating an appropriate education system. Children learn better in their mother tongues. Ethnicity, language and culture are deeply intertwined and it has been demonstrated that children acquire language to belong to a community, to fit in with its norms. When they are encouraged to acquire literacy in this first language they develop well but when literacy is taught in a second language against which their own is devalorized, a condition known as subtractive bilingualism develops, whereby the child ceases to progress in the both languages. Efforts were made in Haiti to avoid this through the establishment of a standardized orthography in 1978 and a language education policy in 1987, but the latter was never properly implemented. The most forceful issue has been the incapacity to train teachers. Fifteen-year-olds graduating from high school go back immediately into the school as teachers. We must not underrate the extreme thirst for knowledge of the Haitian people. In 2000, as we spoke nightly, crowds thronged the venues and asked myriad questions. They would return nightly until these were answered. Their misunderstanding of their situation was profound, however, for they blamed themselves and their language for their impoverishment. They were amazed to find that there were successful independent Caribbean nation states for they had been brought to see success solely in US terms; they were empowered by the very notion of a Trinidad and Tobago which was self-sustained. In Haiti, we see a society in which coercive and discursive control has been profound and within which the path to democracy is only slowly being forged; entailed within it is a battle over language, over having a voice at all. If we look back to the ways in which the young adults we spoke to viewed their own position we can observe how insidious such control is. Without French and without literacy, they have been without an effective voice of their own, receiving only their own ignorance and failure from those in power. The government system has kept them subjugated and illiterate through a French official dictatorship which has consistently exploited them. In such circumstances Kreyòl has become the symbol of Haïtiennité: though the language is both loved and despised through its inherited representation, it gives a voice to those who have none. From the 1980s people have increased their demand for representation on radio which has become an ‘open microphone’ for the democratic movement. The delivery of news in Creole has brought access to happenings internal news for the first time. But twenty years, during which violent oppression has continued, is too short to change people’s image of themselves. Externally, under-representation and misrepresentation also undermine the country. I have alluded to Haiti being off the world’s radar before the earthquake. That is the power of modern media: if you are not their focus then for the rest of the world you do not exist. The media have reported that the world stands to account for the long-term condition of Haiti but the media must take their own share of responsibility. In the present crisis there has been much balanced coverage, but a ‘looting’ focus has also been established. Discerning readers have made comparisons to Hurricane Katrina when victims were ‘refugees’ and ‘looting’ was the label used to describe African-Americans searching for food. In Haiti persons looking for food have been referred to as ‘scavengers,’ and photographs labeled ‘looting and lawlessness’ show innocent people being harassed by violent police and military. The tragedy we see least in the media, is the extent of police brutality: one 15 year-old, was photographed, shot dead, over some worthless pictures she probably thought she might sell to buy food for her family. In our local press, the reports from returning groups have been mixed. Some have clearly been distressed by the horrors but others have spoken of incipient violence in ways that have not been positive. In The Guardian of Saturday January 23rd (A5) we read a headline ‘T and T charity group mobbed in Haiti.’ On reading the article I found no evidence of ‘mobbing.’ Church doors were closed when those waiting for food started to press forward, but this was inevitable, for the evidence suggests that the majority have not received food and water despite the strong effort and many were watching their young and old die. The orderly lines we see in many photographs are a testimony to the people. Why we must consistently undermine the Haitian people, even now, is unclear. The Caribbean must support the people of Haiti. Their entire life experience has been devastating. The capacity for survival which they have displayed is the greater because of what they have learnt to endure. We can never make up for the loss of life but, beyond that, a spotlight has been shone. The past problem has been one of handouts which have robbed people of their self-respect and militated against sustainable growth. Amongst the plans, we need to return to education within Haiti. Years ago, a plan was put to the CARICOM Secretariat for a language education project which took into consideration the physical, social-psychological and ideological factors. Any such plan must entail societal adjustment for proper implementation, so that schooling is related to community goals and provision of food to children as well as other skills development. Trainer training programmes in all languages to be used and taught are very important, since language is the vehicle of all other education. Only an educated people can transform Haiti and it has to be transformed ultimately by its own people, empowered in a way that can enable them to assume leadership in their communities and develop small scale industries and businesses. Haitians have been a profoundly hard working people but have lacked the educational support that would make them meaningfully independent. We can hope to do something about that now. —The Dept. of Liberal Arts is preparing to mount language courses in Haitian Creole for experts gong in to Haiti as part of the relief effort, and to offer language training and language teacher training to Haitian students/teachers, in collaboration with the Centre for Language Learning. This is an extract from Professor Youssef’s Inaugural Professorial lecture, Language, Education and Representation: Towards Sustainable Development for Haiti. Please go to http://sta.uwi.edu/news/ecalendar/event.asp?id=1133 for the full lecture. |

The catalyst for this lecture was the death of Pierre Vernet, Dean of the Faculté de Linquistique Appliquée in Haiti, along with those colleagues and students who were in the building when it collapsed in the earthquake of January 12. Pierre had worked tirelessly to bring an effective language education policy to the territory and I had last seen him when he had invited a group of linguists into Haiti to give a series of lectures on language education policy. That was in January 2000, exactly 10 years from the day of his death. The work he was doing is needed even more today as part of the effort to bring the Haitian people to empowerment from within.

The catalyst for this lecture was the death of Pierre Vernet, Dean of the Faculté de Linquistique Appliquée in Haiti, along with those colleagues and students who were in the building when it collapsed in the earthquake of January 12. Pierre had worked tirelessly to bring an effective language education policy to the territory and I had last seen him when he had invited a group of linguists into Haiti to give a series of lectures on language education policy. That was in January 2000, exactly 10 years from the day of his death. The work he was doing is needed even more today as part of the effort to bring the Haitian people to empowerment from within.