|

|

|

|

March 2015 |

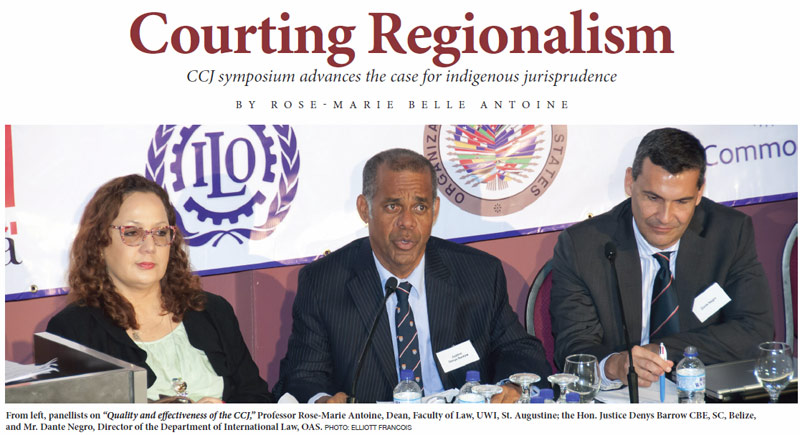

It was as good a Wednesday as any to open up the case for regionalism again. And from the way the Noor Hassanali Auditorium (newly bedecked with its official commemorative name plaque) was packed, it was evident many thought so too. And so the afternoon of January 21, 2015 whizzed by at the CCJ Symposium, which had convened with the purpose of Advancing the Case for Regionalism and Indigenous Jurisprudence: Positive Dialogue to Promote Accession to the Caribbean Court of Justice. This event, examining the rationale for and judgements of the Caribbean Court of Justice was timely, given that it celebrates its tenth anniversary this year. Six constitutional and legal experts on two panels presented powerful arguments to Trinidad and Tobago and other countries in the region which have not already adopted the CCJ as their final appellate court. In the current jurisdictional arrangement, all CARICOM countries, with the exception of the Bahamas, have already acceded to the original jurisdiction of the court, that is, concerning CSME matters. However, thus far, only Barbados, Guyana and Belize have accepted the appellate jurisdiction, though Dominica and St Lucia have signalled their intent to do so. Grenada and Jamaica will hold referenda to assess the question. In the first panel, jurists from Australia and Canada, sister Commonwealth nations, discussed their eerily similar experience to the Caribbean on the road to replace the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom with their own final appellate courts. In those countries too, self-doubt and over-caution bred from colonialism had handicapped the final liberating actions toward full judicial sovereignty. Yet, experience showed these countries that they should have taken the step earlier. Indeed, in Australia it was demonstrated that even half measures, such as accepting constitutional appeals only, had been insufficient and “messy,” in the words of Hon. Justice John Alexander Logan RFD. Both Australian and Canadian judges highlighted the significant gains in developing an indigenous jurisprudence that had occurred after abolition of appeals to the Privy Council. Significantly, Professor Benoit Peltier, a constitutional expert from Canada, spoke on the evolution of the role of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), and explained how the SCC’s establishment had signalled the end of what he referred to as “judicial colonialism” and the development of judicial independence. One of the pivotal moments at the symposium came when Mr. Reginald Armour SC, the panellist representing the Law Association of Trinidad and Tobago, confirmed publicly, for the first time, his organization’s support for Trinidad and Tobago abolishing appeals to the Privy Council. In his view, the concerns about lack of capacity, competent judges and sufficient resources to man the court, were no longer credible. He found no rational basis for the now lessening fears toward adopting the full CCJ jurisdiction. The second panel assessed the evolving jurisprudence of the CCJ in its 10 years. I focused on the impactful original jurisdiction decisions of Myrie, a Jamaican national who sued the Barbados Government about freedom of movement and the TCL cases which involved CSME arrangements in the region, which had been impressively handled and demonstrated the sophistication of a court that spills over into its appellate areas of inquiry. My assessment was based on three guiding principles: (1) The CCJ’s adherence to established principles of independence, integrity and fairness; (2) The CCJ’s consistency with internationally accepted norms of judicial decision-making by a superior court, i.e. using reasoning and logic; ingenuity; accepted principles of law and keeping in touch with emerging judicial and legal trends, – but nevertheless having the ability to be innovative when necessary; and (3) The CCJ’s ability and willingness to create an indigenous (Caribbean) jurisprudence – adapting to our particular local circumstances without sacrificing appropriate judicial principle, a long cherished goal. Landmark cases of the court to date were the basis of my analysis as they involved a wide variety of subject areas, including test cases. They have dealt with innovative issues such as the introduction of the concept of legitimate expectation in Death Row cases with international dimensions, forensic orthodontics and misfeasance in public office. It is clear that the Court is infused with a deep understanding and appreciation for cutting edge principles such as fairness and proportionality. Further, it has been influenced by established principles of international human rights. An important element was the embrace of international law instruments, even when these were not incorporated into domestic law, as explained in Boyce. The CCJ had also seized the opportunity to correct contradictory decisions on the death penalty emanating from the Privy Council and displayed a refreshing understanding of the realities of Caribbean legal systems. These are all accepted parameters of a final court that is consistent with and well entrenched in universally accepted judicial traditions. The CCJ has approached its task with independence, integrity and intellectual rigour and has exhibited a fine tradition of sound judicial reasoning. One aspect of the value of the CCJ that is often overlooked is its great potential to develop the hybrid legal tradition that is still prevalent in the region given that in some countries such as Guyana and St Lucia, there is a mixture of the UK common law legal tradition and the civil law based on Roman Dutch French law. Denys Barrow, SC, former OECS judge, examined the aspects of the CCJ’s body of work that highlighted its recognition and adherence to now established principles of international labour standards as identified by the ILO. He alerted the audience to a landmark decision now before the CCJ concerning the rights, in particular, Mayan land rights, of the indigenous peoples of Belize. These standards flow from the ILO’s Convention 169. It would be the first opportunity for the region to consider these important issues at this level, an issue of increasing significance to Trinidad and Tobago. He saw the CCJ as continuing the tradition of “direct reliance on ILO Conventions, including unratified conventions, as sources of primary and previously undeclared and unestablished rights, as well as ratified conventions which have been transformed into domestic law.” He was of the view that given the CCJ’s general pronouncement previously on these international law influences, the body of now established international law principles on indigenous rights would be addressed adequately in the upcoming Mayan Land Rights case. “The CCJ has used international law as a guide for interpreting domestic law; as offering jurisprudential principles based on international law; and to strengthen a decision based on domestic law,” he said. On the niggling question of independence, Armour agreed with me that this was not seriously in doubt, since the arrangements for protecting the independence and integrity of the CCJ are among the finest in the world – and UK jurists themselves have commended the region on this, as did the visiting jurists at the Symposium. There is a separate Judicial Commission that selects judges, unlike the political appointments we see in the US and the UK. Moreover, the jurisprudence of the court to date makes it clear that it is no slave to any government. Armour and I both recalled the enduring remarks of lead Prime Minister for the CCJ, Dr. Kenny Anthony, when he said in the feature address at the inauguration of the court in 2005, that the establishment of the CCJ was a “leap into enlightenment,” recalling “the distinguished contribution that the region’s legal practitioners, . . . have made elsewhere in the Commonwealth and internationally.” This includes sitting as Chief Justices in many parts of Africa, judges at the International Court of Justice in The Hague and other international tribunals. Indeed, Anthony remarked, “in ‘per capita terms I doubt if any other community in the world has served the world-wide cause of justice more comprehensively and more consistently than has the Caribbean . . . The Caribbean is not a fledgling state approaching tentatively the threshold of the rule of law.’ Thus, establishing a CCJ was “not a leap into the dark, to be feared, but a ‘leap to enlightenment’ to be embraced.” The audience heard that former President of the CCJ, Michael de la Bastide had also stated that in looking at the actual cases that went before the Pricy Council, more often than not, the PC agreed with the local courts’ decisions and merely adopted their reasoning, which endorses the strength of our local judiciary and indeed, those who present arguments before them. Significantly, all of the presenters were of the view that the strengthening of the CCJ by accepting its appellate jurisdiction would advance the rule of law in the Caribbean and redound to the benefit of the regional integration process. The Symposium, jointly hosted by the Faculty of Law, UWI, St. Augustine and the High Commission of Canada to Trinidad and Tobago, was supported by the ILO, OAS, Commonwealth Secretariat and UNDP. It was attended by more than 100 participants, drawn from the judiciary, the Bar, academia, the private sector and civil society, and, notably, the then Acting President of Trinidad and Tobago, The Honourable Timothy Hamel-Smith, The Honourable Chief Justice Ivor Archie, Trinidad and Tobago Minister of Justice, Senator the Honourable Emmanuel George, and CCJ President, The Right Honourable Sir Dennis Byron. Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine is Dean of the Faculty of Law, UWI St. Augustine. |