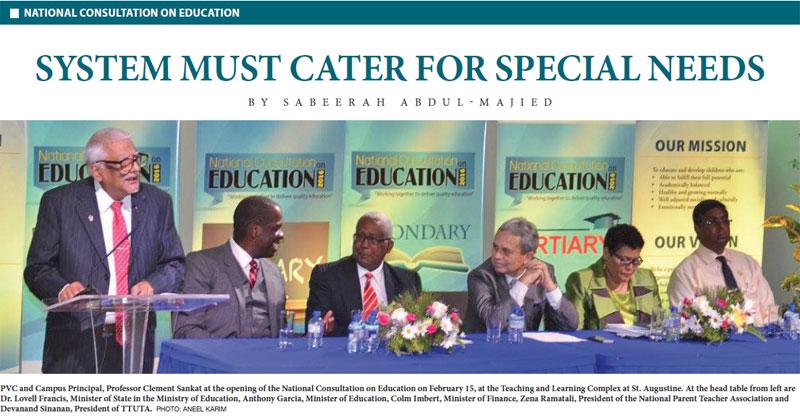

The UWI School of Education (SOE) made a significant contribution to the three-day National Consultation on Education (NCE). Our experts’ advice ranged from best assessment and health and family life practices to early childhood interventions to curb school violence. SOE staff also addressed meeting students’ special needs through a comprehensive, national inclusive education programme. To lend further support to this Ministry of Education initiative, staff and graduate students also served as moderators and rapporteurs for panels at the three venues.

At the first consultation, Dr. Jerome De Lisle shared his expertise in public examinations and large scale assessments. He cautioned Trinidad and Tobago against benchmarking and borrowing assessment policy from countries, which are high performing in international assessment. He advised that the focus should be on formative assessment (to monitor student learning and provide ongoing feedback to improve teaching and student learning). This is done in Hong Kong and Singapore. Finland also focuses on this type of teacher-led assessment from the early grades. Reforms in the US also include such a focus and consider the use of challenging performance assessment for performance understanding among students.

He lamented that this focus is missing in both teacher preparation and system emphasis in Trinidad and Tobago. High stakes summative assessments (like SEA and CSEC which evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional unit) continue to be important for benchmarking and providing the full picture of learning nationally. Dr. De Lisle warned that we must be cautious of trying to use one assessment to (1) select and certify; (2) promote and support learning; and (3) monitor student learning standards. Implementing these kinds of assessments in the classroom require significant improvements in teacher preparation and professional learning. He also recommended a review of policies which promote measurement-driven instruction (as contained in current SEA/CAC practice).

At the Inclusive Education forum, Dr. Elna Carrington-Blaides reported on a recent UWI study which indicated that approximately 37% of the students have some type of emotional behavioural disorder; far greater than the projected 15% to 25%. She also lamented the lack of legislation and a framework to guide the delivery of inclusive services for students with special needs. Her recommendations included field research to accurately identify the prevalence of various disabilities; teacher training to focus on differentiated instruction to assist all teachers to modify curriculum and instruction to meet the needs of diverse students; and developing a framework for identifying and matching students with special needs to required services.

As an early childhood specialist, I noted that school violence usually starts as challenging behaviours in pre-schools and early primary classes. Some of our gifted students may be among those displaying behavioural problems because school is boring. Left unattended the problems escalate. In the absence of interventions for addressing challenging behaviours, young children can become bullies or “troublemakers.” It is critical therefore to make behavioural interventions before children reach age 6. Thereafter interventions are still possible but more complex and costly. While the home situation is often the root cause, reasons for “acting out” behaviours are varied and can be exacerbated when schools are not equipped to assist students with social and emotional problems.We therefore need research to understand the scale of the problem. We also need to introduce policy, teacher professional development and developmentally appropriate intervention models to assist young students with challenging behaviours.

All stakeholders, including families, should be included to identify and solve problems.

In relation to health and family life issues Dr. Bernice Dyer-Regis, Dr. Madgerie Jameson-Charles and MPhil student Chinyere Onuoha, stated that 60% of all deaths in Trinidad and Tobago are caused by health behaviour and lifestyles established early in life. The Trinidad and Tobago Global School Health Survey (2011), found that 26.2% of students were overweight. Further, only 29.2% of students were physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day on five or more days over a seven-day period. Statistics also revealed smoking, alcohol and drug abuse problems among students. The good news is that schools can promote good health among students through health and family curriculum and everyday practices. The Ministry of Education has already produced policy and curricula for Health and Family Life Education. They need to fully implement curricula at the primary and secondary levels; improve teacher training; and re-visit the School Health Policy to facilitate the development of health promoting schools.

–Sabeerah Abdul-Majied lectures in Early Childhood Education at the School of Education, UWI St. Augustine.

|