“Manufacturing is the backbone of developed nations,” Professor Boppana Chowdary, Head of the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering at UWI St. Augustine, tells me for the second time. “Manufacturing is the backbone of developed nations,” Professor Boppana Chowdary, Head of the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering at UWI St. Augustine, tells me for the second time.

The first was more than a year ago, in a discussion on 3D printing, the manufacturing sector and the Caribbean’s need for diversification.

A year later, and the conversation is almost the same. In truth, with some variations, the conversation has been the same for decades. Some would say since Independence, as the colonies whose role was to supply crops to the colonial power found themselves with vulnerable, agrarian economies.

Since those days there has been an understanding of the necessity for economic diversification and the growth of manufacturing. And there has been progress – just not enough. So the conversation continues. But perhaps the time has finally come for the dynamism required to make diversification a reality.

With years of low growth and high unemployment behind it and more of the same on the horizon (recent estimates from the ECLAC forecast Caribbean growth in 2016 at 0.3%), the region has a critical need for new solutions. And now even Trinidad and Tobago, bolstered by its energy sector-driven export trade is being hit by low oil prices. On top of this, there are fears of a global turndown, which will affect Caribbean services and commodities. The islands now have more motivation for strong diversification measures than ever before – desperate necessity.

Professor Chowdary has been ready.

“I was at a gathering hosted by InvesTT (one of Trinidad and Tobago’s investment promotion state agencies),” he recounts, “and I told the stakeholders from the manufacturing sector ‘if you are willing to come forward one step, I will come forward seven’.”

As Head of the Department, he is facing a dilemma. The UWI decided to combine the existing Mechanical Engineering Department with Manufacturing with the intention of training a cadre of manufacturing engineers to support an emerging, vibrant manufacturing sector. That sector has not emerged. There is a relatively successful manufacturing sector in Trinidad and Tobago but its contribution to GDP is small (estimated at TT$7,633.2 million or 8.1% of GDP in 2015). But the sector is certainly not enough to attract engineering students away from the far more prosperous energy sector. Nor is it at the level of sophistication in manufacturing technology to even need trained manufacturing engineers.

“Caribbean manufacturing has several challenges,” Professor Chowdary says, “outdated machinery, limited raw materials, expensive or unproductive labour and lack of funding for research. Because of this, Caribbean manufacturing companies are struggling to compete internationally.”

Several pieces have to be put in place for an internationally competitive manufacturing industry to develop in the region, training engineers and researching and developing innovative manufacturing technologies and processes comprise one piece. Without the others it will not work. Several pieces have to be put in place for an internationally competitive manufacturing industry to develop in the region, training engineers and researching and developing innovative manufacturing technologies and processes comprise one piece. Without the others it will not work.

“All the developed and developing nations with strong manufacturing have collaboration between the universities, business and government. That is what we are missing in the Caribbean,” he says.

Universities such as MIT, Stanford, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and many more, routinely collaborate with governments and the private sector to achieve mutually beneficial national goals. In fact, the development of Trinidad and Tobago’s oil and gas-based sector is an example of precisely this kind of collaboration for economic development. This level of partnership, each performing its role in a clearly defined strategy, is what is required to develop a sector.

What is interesting is that knowing the limits of his power in the situation, Professor Chowdary, a very soft-spoken man (every sentence seems to trail away into a whisper, the more emphatic his point, the quieter he becomes), remains resolute. If training and research is not enough, then the next step is big-picture strategy and advocacy.

“Bygones are bygones, we have to do what we can do now – The UWI, industry and governments,” he says.

The closer the better

A good example of the kind of limitations regional manufacturing faces is the ubiquitous water bottle. Water bottles are everywhere and we manufacture them locally. What we don’t manufacture is the bottle cap. That means every water bottle you see or buy, even though local manufacturers are involved in the process, adds to the import bill, the negative trade balance and the loss of US currency.

Why is this? The cost of acquiring the raw materials and manufacturing the cap is three to four times what it costs to import them. And why is it so much more expensive – because of import duties on the necessary raw materials and manufacturing process-related costs. Put another way, in this scenario manufacturers are limited because of structural hurdles that make local manufacturing inefficient.

“As a business person you cannot justify the risk,” Professor Chowdary says. “There is no research, no encouragement, no incentive.”

This is why he believes the business-government-university partnership is so crucial. Policymakers’ role is to create the enabling environment through laws and regulations and provide incentives through direct funding or provision of resources to the industry and the university. The industry and entrepreneurs invest in modernisation and labour and embark on new manufacturing ventures.

As for The UWI’s role – Professor Chowdary has no shortage of ideas:

“We definitely need to do more. We must build confidence in the university. If we are not showing anything, if we are sitting in our offices, if we are not exhibiting our talent, nobody will realise our strengths.”

Confidence, the Professor believes, is one of the keys to making change work, especially to bring the manufacturers and entrepreneurs on board, who, more than the other groups, face fatal financial risk if new schemes fail.

To instil greater confidence, the department will host exhibitions of mechanical and manufacturing engineering projects every May/June to showcase the capacity of its students and staff. In addition, working with academic staff such as Rodney Harnarine (who has been featured in earlier issues of UWI Today for his work with students in agricultural innovation, see http://sta.uwi.edu/uwiToday/archive.asp) the department has designed, constructed and sold a functional model of a channa-splitting machine. There are several other projects in the works focused specifically towards food processing.

“Our approach is incremental,” he says. “We are targeting specific sectors like agriculture to show what we can do. For example, we are working on cassava grating machines that can be used to process cassava flour from what is being farmed in Moruga. This will enable farmers and the community entrepreneurs to sell a finished product to stores and bakeries.”

This goes beyond showing what The UWI can do to contributing directly to the development of the sector. The benefit of this as well is that by using machines developed through UWI research the cost to manufacturers is much lower. The university’s research objective is to contribute to development and impact on the society, not turn a profit.

One of Professor Chowdary’s most ambitious goals is the creation of a design and manufacturing innovation centre that is specifically tailored to meet the needs of industry – regional and international.

“I have discussed a proposal with Professor Stephan Gift, Dean of Engineering, for a school of engineering that focuses more on the business and commercial aspects,” he says. “I would like a space where companies can set up offices within the institution so that we can collaborate more closely. We can tweak our curriculum and training programmes to suit their needs. We can support their existing operations. We can create a pipeline for our students from the university to employment in the industry.”

The Professor points out that this type of institution is nothing new. In fact, he has experienced it first hand at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, where these types of relationships with big multinational players in science, manufacturing and technology are the norm. To this end he has already been in discussion with regional and even international players about partnering with The UWI.

“We will be the engineers to meet their requirements,” he says, “whatever they want.”

MSc in Manufacturing Engineering and Management

No matter what measures the Department takes, it will come down to the quality of its educational programme and its graduates. Because of this the MSc in Manufacturing Engineering and Management is a comprehensive programme that stresses the technical, professional and managerial aspects of the profession.

“I am linking the programme with the current and future needs of the industry,” Professor Chowdary says. “To have confidence in us the industry needs to see our capabilities. We have to show them that there is no need to send their engineers for training in the US or Canada.”

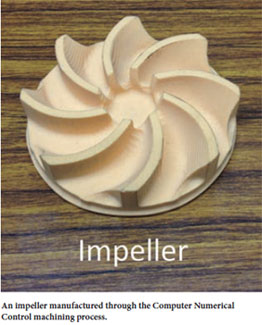

The programme will provide training in flexible and cost-effective manufacturing technologies like computerised numerical control (CNC) and 3D printing. With six compulsory and four optional courses and extensive hands-on experience in the laboratory and on machines, the MSc is aimed at producing “complete” manufacturing engineers.

“The industry needs a crossbreed of engineers and technicians that will service and deal with all areas of mechatronics. If I’m going to hire a technician that technician must be capable of doing multiple jobs,” he says.

And like the Department Head himself, the MSc graduates, apart from specialising in modern design and manufacturing, will have the big picture view of Caribbean manufacturing and be its advocates and enablers.

“They are going to give the kind of awareness and exposure we need to the people in the system. These manufacturing management engineers will implement what they have learned and show its benefits,” he says.

The potential of these moves and the persistence of the man behind them are hard to deny but the forces of inertia have been more resolute than any plan of change when it comes to Caribbean diversification. Since our last interview it is clear that Professor Chowdary has come up against the inertial wall that has resisted so many efforts to drive past it. Nevertheless, he is still fighting.

“People keep asking ‘where is manufacturing in this country?’ Who will answer those questions for this region, God? We are the people who must answer this question. We are the people who must create change.”

Professor Boppana Chowdary can be reached at Boppana.Chowdary@sta.uwi.edu

–Joel Henry is a professional writer and media consultant. |