A black sorrel flower soaked in white rum, spices and sugar, then dipped in dark chocolate – have you ever eaten something so decadent? A black sorrel flower soaked in white rum, spices and sugar, then dipped in dark chocolate – have you ever eaten something so decadent?

I have; thanks to Matthew Escalante, the chocolatier at UWI’s Cocoa Research Centre (CRC).

Matthew, 28, trained at the Trinidad and Tobago Hospitality Institute in Chaguaramas (TTHI) before joining the CRC to do his Master’s degree in Food Technology.

Between classes Matthew whips up vanilla ganache hearts and gold-patterned cardamom-and-pepper squares that joyfully explode in my mouth. It’s a tough gig...

He is constantly experimenting with flavours and textures. His bubbly personality belies a well-trained palate and his carefully considered alchemy. Yes. Alchemy.

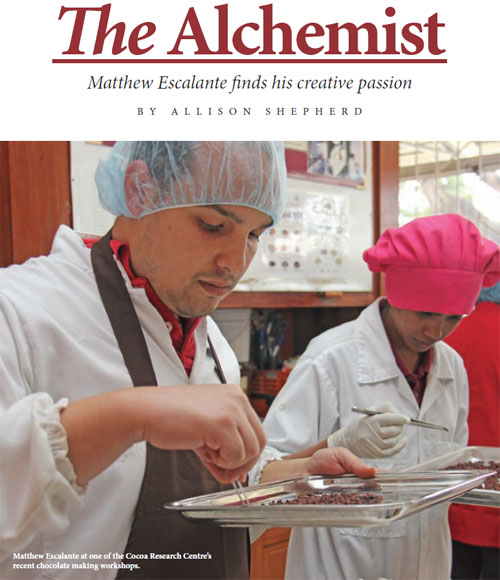

When we meet, Matthew is in a white lab coat, pacing up and down the laboratory-cum-kitchen, brimming with excitement and talking at high speed in the language of food.

“I’m fat, and I love food,” he says. “Food is about passion. If you lose your passion, you can’t create.”

His culinary acumen honed by years in restaurant kitchens, led Matthew to CRC as their chocolate maker in February 2014. Working on a carbonated cocoa pulp drink as his final year project as an undergrad in Nutrition and Dietetics, brought him into close contact with the CRC. His research won the Freeman Prize for best third-year undergraduate project in cocoa, so when their current chocolate maker left for French Guiana, they immediately thought of Matthew.

Matthew takes the raw cocoa bean from fermentation to the artisanal stars and hearts that melt in my mouth and leave me craving more. Which apparently only the best chocolate can do: no aftertaste, and you can’t stop eating. The fridge in his lab is filled with Ziploc bags of the batches of chocolate that came out with the perfect desired taste: raisin, red berry, passion fruit.

He never stays still and is up and down the lab, opening cupboards and flasks, unzipping bags and unwrapping more delightful concoctions.

“Do you like milk chocolate?” he asks.

I hesitate and tell him I now find it too sweet; I used to eat loads of milk chocolate and have now switched to dark.

“Most people think it’s bad and dark chocolate is the only one that’s good for you, but there’s no ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ it’s just different.”

Matthew slides open a bag that holds the biggest slab of chocolate I’ve ever seen, breaks off a chunk with a satisfying snap and hands me to taste: it’s silky and raisiny, a result of Matthew’s hand tempering that adds shine and snap. I am amazed by its subtle delicacy: not too sweet; I immediately want more. This is milk chocolate? It is nothing like the stuff you find on supermarket shelves.

We then try a tiny frilly-edged button chocolate that has a distinct passion fruit taste. Absolutely delicious. Matthew pops one into his mouth to confirm my findings. He’s delighted to help.

The beans CRC gets for chocolate making are from the International Cocoa Genebank in Centeno and are picked from their fields and sent as one batch.

The first stage after the beans arrive is fermentation. Matthew takes me to the fermentation building where the raw beans are in ventilated wooden boxes covered with a layer of banana leaves, then a layer of the crocus bags the beans are transported in. The sour flies that flit around us influence the growth of yeast.

There is a not unpleasant hot wine-like smell in the room with an underlying bitter chocolate aroma. Matthew measures the temperature of the fermenting beans.

After three days the beans have reached a temperature slightly above 44 degrees Celsius and are ready to be turned. They are then left for six to eight days. After fermentation they are taken to the roof of the Frank Stockdale building (home of the CRC) to dry. We take the ancient lift to the roof where the beans are laid out drying in the sun. It is a hot day and the drying gets rid of any mould.

His chocolate only uses hand-picked beans. “They should be the same size, plump, no splits or cracks and mould free,” Matthew explains.

He chooses a couple of already roasted beans, breaks them open and fills my hand with cocoa nibs. “Try them.” They’re bitter with a slightly acid sharpness.

Flavour depends on each stage of the chocolate-making process from bean to bar including genotype, roasting and conching.

Matthew, always experimenting with flavour, is isolating the beans from each field to see if the chocolate has a unique “field” taste. This could then influence the notes of the chocolate he produces.

“We are trying to determine the flavour potential of each of the Centeno fields,” he says.

Experts like CRC’s food technologist Darin Sukha are trained to detect 40-50 flavour notes. Someone like me should be able to detect around seven including floral, fruity, nutty and earthy, Matthew says.

I’m thinking I should eat some more – just to see if I can improve.

To learn how to make chocolate for yourself join one of CRC’s classes. Courses start at $3000.

–Allison Shepherd teaches Medical Communication Skills at the Faculty of Medical Sciences, UWI, Eric Williams Medical Sciences Complex in Mt Hope. |