|

|

|

|

May 2010

|

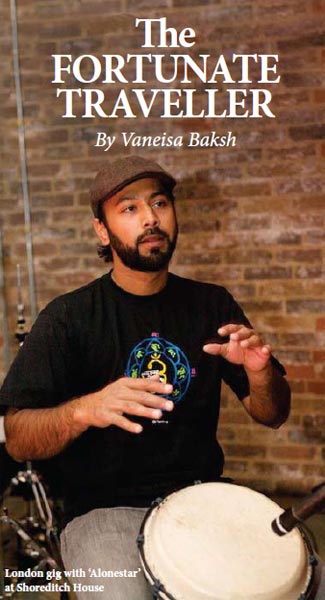

He tells of the flurry of activities he’s always flooded his life with—the music: trumpet and the drums of his heart; the sports: football, softball, rafting, hiking and the cricket of his heart; the clubs and organisations; the constant moves: 16 schools in five countries—and all you can wonder is: but how does he stay so neat? For someone who lives so fully that sometimes, “I need a vacation from my own life,” Sharan Chandradath Singh ought to look ruffled, dishevelled even, but apart from the glint occasionally shining through the Prada glasses, he appears immaculate and imperturbable. It must be that formidable pair—genetics and environment—that shaped this 35-year-old. His Indian mother, Anita, once produced and presented television films locally, like ‘Mehefil’ that sought to highlight cultural elements. She cut a serene, composed picture, with her elegant clothing and refined diction, yet when you look up her online profile, hers is a beehive of activity: author, chef, teacher, graphic designer, script writer, producer and presenter; and you see the lineage of the man. It’s reinforced by the Trinidadian father, culturally active diplomat Chandradath Singh (the family bears his name) whom memory recalls clad in white with drums before him. His two younger brothers, Shyamal and Keshav carry the family’s artistic traits, but wear them much more openly. Looking at images of the three, it is like the youngest lets it all hang out because he had the baby’s freedom to do so; the middle one took a moderate road, and the eldest chose a double life. The things you see in pictures. But the pictures came after the interview—I hadn’t yet seen Keshav’s LAZA beam band’s website, which boasted that “his sound is increasingly without genre” nor the two brothers performing in Kin – Sibling Rivalry—so a lot of what he was relating suggested that he was one souped-up kid. When we spoke, Sharan had just returned from London, where his flight to Trinidad had been delayed because of the volcanic ash that grounded European travel. Since most of his assignations with the colleges he’d been visiting to develop relationships on behalf of The UWI were done, he took the opportunity to visit two of his childhood homes and play at a concert, while keeping constantly in touch with the International Office at the St Augustine Campus of The UWI, where he is the Director. It’s his second incarnation at The UWI; he was first at the Business Development Office (BDO) when Dr Bhoendradatt Tewarie was principal. He’d followed his BA in International Studies (with a double minor in Spanish and Business Administration), with Masters Degrees in both International Business and International Administration, but when he returned to Trinidad and reported to the Service Commission as he was required to do for his OAS Fellowship, he received a sluggish response. His fortuitous meeting with the BDO’s Director, Dr David Rampersad, opened the door and for the next three and a half years, he learned university ropes. Then something entirely different appeared at PricewaterhouseCoopers, and he took off. Proficient now in working within the intricacies of international environments, Sharan realised that in addition to his “spontaneity, drive and enthusiasm” he had acquired a skills set that “combined very unique characteristics.” From PwC, he’d worked on transformation projects at various ministries, and had built systems for various organisations, benefiting from the global scope of his company to source best options. “Then this opportunity came up, and it was a very hard decision to make,” he said of the UWI position. “I felt I could get closer to the future of the country here at UWI.” So he bid his potential PwC partnership goodbye and set up the International Office, and hasn’t regretted it one bit. “I came back and did a mega situation analysis,” he said, determining there was a lot of potential, so for six months, “we developed systems and templates and now we can shift gaze” to the internationalization of UWI, he said. Critical to this goal is the accreditation process, which “allows you to take a look at yourself in a structured manner,” he said, adding that it helps staff to internalise the strategic objectives of the institution. “Internationalization to me is the sustained global competitiveness of our institution, and removing the constraints of being the best regional institution to being an internationally competitive one,” he said. His argument is that it is no longer enough to be the best regionally; not with so many international ones now operating freely in the Caribbean. “We need to figure out how we are going to position ourselves in the world,” and the key is to “focus and differentiate.” One of the drivers at the International Office is its student, faculty and staff exchanges and scholarships. Theirs is the mantra of nurturing “global citizenship.” He feels it is important to let students experience the world outside, because “borders are falling and we are becoming amorphous” and it has revived nationalistic feelings. His concept of global citizenship “means becoming more sure of who you are as a Trinidadian and Tobagonian as you go out in the world.” As the son of a diplomat, who spent years at a time in India, Canada, the UK and the USA, he found his sense of being Trinidadian was reinforced by those outer exposures. Moving through different societies created the self confidence that ripples through his slight frame with that remarkable intensity. He’s at home anywhere in the world, and that is precisely where he wants to place The UWI. |