|

|

|

|

May 2013

|

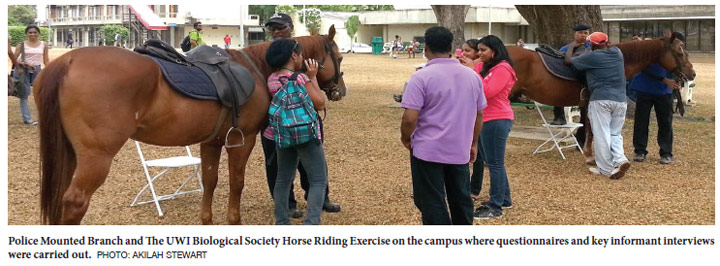

People around the world drew back in horror at the clandestine mixing of horse meat with other types of meat in some parts of Europe. This raised a number of ethical issues about the rights of consumers to make fully informed choices regarding what they eat and about the safety of horse meat for human consumption. Here in Trinidad & Tobago, horse meat has for several years been advertised by Carnival fete promoters as an exotic item on the menu in the hope of differentiating their event from the rest. Four graduate students of Bioethics in a course lectured by Prof Dave Chadee – Kerresha Khan, Hema Ramdial, Maurice Rawlins and Akilah Stewart – posed a question: ‘is the meat in fact safe to eat?’ Armed with their videographer Somdutt Bhaggan, they set out to determine the bioethical issues surrounding the consumption of horse meat in Trinidad & Tobago, where the horse meat scandal is not quite a scandal. In recognizing that horse meat is increasingly being consumed by the national community, the team of bioethicists used surveys, key informant interviews and review of secondary sources to gather their information. Their quest took them to popular street food areas in Valencia and St James where they learnt that geera horse and hops was usually sold on a Friday night or Saturday morning. There was even a lead for a horse meat vendor in Petit Valley. Horse meat was apparently not difficult to come by, if you knew the right people. A survey showed that the largest proportion of horse meat eaters were in the 15 to 25 age bracket. Indeed, 7.9% females versus 45.1% males had consumed horse meat previously. A similar pattern existed for those willing to try horse meat: 22% of females versus 65% of males were willing to consume horse meat. Interestingly, the most popular reasons given for not consuming horse meat were the fear of steroids and painkillers or because of a sentimental attachment. To the others who consumed horse meat, it was ‘just meat’. Problems identified by the team concerned the potential human health issues due to consuming horse meat and the treatment of the animals themselves. There was some indication that one painkiller, phenylbutazone, which was found to be associated with cancer in humans is still used as a painkiller for horses. Since most consumers were not aware of the source of the meat they ate, it was quite uncertain whether the recommended 3-6 month period for horses to be off all medical treatments prior to slaughter, was upheld. The UWI bioethicists noted that horses in Trinidad & Tobago are not reared for human consumption, in which case there would be oversight on the chemicals administered. Too often respondents made the comment that “since horsemeat isn’t commonly consumed, it shouldn’t be too much of a worry!” The bioethicists countered with ‘how many times do you really need to consume chemically treated horse meat to be affected by it? Just once may be enough to trigger allergic reactions to these chemicals.’ Ultimately, they say, it is up to each individual to make an informed decision on what they consume or, as the saying goes, caveat emptor (buyer beware)! Kerresha Khan is a PhD student in Environmental Biology; Hema Ramdial is an MPhil student in Plant Science; Maurice Rawlins a PhD candidate in Environmental Biology; and Akilah Stewart an MPhil Student in Riverine Ecosystem Services. All are in the Department of Life Sciences. They presented their research findings orally and via video at "People , Science and the Environment", the 3rd Annual Research Symposium staged by the Department of Life Sciences in April.

|