|

May 2014

Issue Home >>

|

A common error in describing migrants is to group them with a majority nationality or archetype. One such obvious mistake has been to assume that all Caribbean migrants in post war Britain were Jamaicans. Similarly in Trinidad, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the English, Scots and Irish were taken to be a largely undifferentiated group. Yet Ireland and the Caribbean have been linked for over four hundred years since the early transportation of Irish indentured labourers to the British colonies such as Barbados, and later Jamaica and Montserrat in particular. As Nini Rodgers’ research has shown, the Irish were also found in other Caribbean destinations, among them the French colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique and Saint Domingue, where they shared the Catholic faith. Migration of the Irish to Trinidad occurred much later, primarily from the nineteenth century onwards, when the Crown Colony system of government included migrants from Ireland, whom, as we shall see, came largely as managerial or professional classes, rather than as poor or destitute servants to this colony. A common error in describing migrants is to group them with a majority nationality or archetype. One such obvious mistake has been to assume that all Caribbean migrants in post war Britain were Jamaicans. Similarly in Trinidad, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the English, Scots and Irish were taken to be a largely undifferentiated group. Yet Ireland and the Caribbean have been linked for over four hundred years since the early transportation of Irish indentured labourers to the British colonies such as Barbados, and later Jamaica and Montserrat in particular. As Nini Rodgers’ research has shown, the Irish were also found in other Caribbean destinations, among them the French colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique and Saint Domingue, where they shared the Catholic faith. Migration of the Irish to Trinidad occurred much later, primarily from the nineteenth century onwards, when the Crown Colony system of government included migrants from Ireland, whom, as we shall see, came largely as managerial or professional classes, rather than as poor or destitute servants to this colony.

My contemporary familiarity with English and Irish cultures and peoples has perhaps made me a little more perceptive of distinctions between closely associated nationalities. Over the last two decades I travelled extensively to what is now known as Northern Ireland and to the Republic of Ireland. My husband, English-born artist, Rex Dixon, had worked in Belfast as a lecturer in Fine Art at the College of Art & Design, part of the Ulster Polytechnic, now the University of Ulster, during the “troubles” from the early 1980s, and survived life in this city in turmoil, despite his Englishness.

During this time he established a close friendship with one of Northern Ireland’s most famous artists, Graham Gingles, and they have remained lifelong friends and colleagues. Graham lives on the Antrim Coast in a small village named Ballygally, whose most outstanding landmark is a seventeenth century castle, now housing the Ballygally Castle Hotel. The pastoral rolling hills and seaside villages, like Cairncastle and Glenarm, and the spectacular views of the Antrim coast, together with the peaceful ambience of the village, has lured us back for two decades now: the tranquility makes for a most productive writing space.

These visits provided me with an increasing interest in and growing familiarity with the history of Ireland. When I began my current novel, a component of which is set in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century on a sugar cane estate in Trinidad, I wanted to make one of my characters an Irishman who had migrated from Northern Ireland to take up a position as an overseer on a sugar estate in Trinidad. What better place to derive his origins than the people and sites I had come to know well through the churchyards and gravestones I had scoured which told the histories of many who had migrated and some who had even returned?

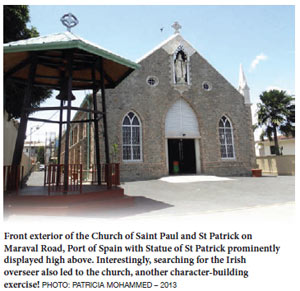

In locating this character in the late nineteenth century, I needed to ensure what were in fact credible occupations for Irishmen in Trinidad at this time. One of the images I came across that supported the historical presence of an Irish overseer was a photograph in The Art of Garnet Ifill: Glimpses of the Sugar Industry.

Searching for an appropriate caption for this photograph which was taken by the Trinidadian artist and photographer Garnet Ifill in 1954 (Figure 1), Brinsley Samaroo, a Trinidadian historian, made reference to a poem entitled The Sugar Cane by Dr. James Grainger published in 1764.

Grainger, a Scottish doctor, poet and translator wrote this poem in flowery eighteenth century prose as a lengthy ode to the sugar cane industry, producing one of the best descriptions of life on a West Indian plantation at this time. So taken was Grainger by the beauty of the crop and the culture of plantation life that he was moved to wonder why the sons of local planters left the West Indies to spend their time in Europe. “While such fair scenes adorn these blissful isles, why will their sons, ungrateful, roam abroad? Why spend their opulence on other climes?”

In selecting Grainger’s poem as a point of departure for crafting his caption, Samaroo writes “Whether it was 1764 or 1954, the sugar cane plantations of the Caribbean had always attracted young English, Scottish and Irishmen. Here the young overseers and managers, attended by their local grooms, gather for the Picton Estate gymkhana.” In doing so, Samaroo acknowledges the established image of power, status and leadership of a generic white British male presence in the sugar industry and on the estates, from the early nineteenth into the twentieth centuries in Trinidad. The colonial control of sugar production dominated until 1975 when the British company Tate and Lyle sold the now floundering industry to the Trinidad government. Thus the scene in Figure 1 is a fairly accurate depiction of the hierarchy of ownership and management on the estates and the industry, as it operated well into the twentieth century.

In my reading of ephemera including the Trinidad Guardian, Port of Spain Gazette and The Mirror newspapers between 1914 and 1920, I had come across interesting information that confirmed the presence of these youngish men who would occupy relatively high rank in the sugar cane industry. By a leap of imagination that one is allowed in constructing a character for a novel, I imagined that this group could very well include an Irish overseer among them.

This is an excerpt from a chapter in a book on deconstructing and using different cultural texts that Professor Patricia Mohammed is currently working on. The chapter can be found here.

|