|

|

|

|

May 2014

|

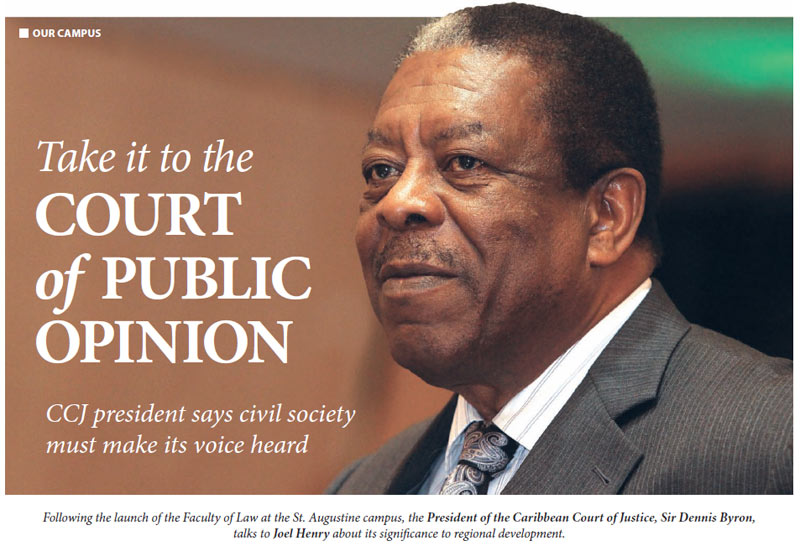

Following the launch of the Faculty of Law at the St. Augustine campus, the President of the Caribbean Court of Justice, Sir Dennis Byron, talks to Joel Henry about its significance to regional development. “Integration to me is not just an imperative for the survival of the region, it is also an imperative to consolidate our identity, a sense of our place in the world,” the late Norman Girvan, Professor Emeritus at the Institute of International Relations, UWI St. Augustine, said in an interview before his death. One of our most respected and steadfast integrationists, I’d been fortunate enough to spend an hour with him as he recounted his dream of Caribbean unity, and the collective energy of his generation for an independent and unified community of islands. I listened as he described how that wave of certainty crashed with the collapse of the West Indian Federation in 1962. The will for integration, he’d learned, ebbed and flowed. Many would argue that we are once again in a period of retreat. As Caricom reassesses its role and the Caricom Single Market Economy (CSME) faces competition from Latin and extra-regional economic communities, integration seems to have few proponents among the island governments. Its advocates share a platform in a public space that seems uninterested in the topic. In some cases they are drowned out by insular and tribal voices that are adversaries even to the idea of an identity that is national, let alone regional. And then there is the law. If there is one area in which the Caribbean community has maintained its momentum, it is in the creation of the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ). For the past nine years the CCJ has advanced—establishing its bench, building its reputation for sound judgments, dispensing justice and serving clients from across the region. Now the court has its eyes set on one of its most important goals: becoming the final court of appeal for the Caribbean. “The time has come to move forward fully,” says Sir Charles Michael Dennis Byron, President of the CCJ. Knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2000, member of the Privy Council, Chief Justice of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, Judge of the United Nations International Tribunal for Rwanda, legal ethicist and reformer—Sir Dennis is not only one of our most accomplished jurists, he is a mighty spokesman for regional integration and independence. “This is 2014,” he says. “I think that after almost ten years people have had an opportunity to see the court in operation. We are no longer a hypothetical court of which you have to wonder who the judges are, how are they going to operate and what kind of judgments are they going to deliver. The teething phase has finished.” The Caribbean Court of Justice Based in Port of Spain Trinidad (although an itinerant court), the CCJ operates with remarkably low visibility for an institution of such importance. This lack of awareness is a concern to the CCJ, especially if it is contributing to delaying the full embrace of the court by the public. “We have been seeking avenues to provide information to the public about the work of the court,” Sir Dennis explained.

Including Sir Dennis, the CCJ bench is currently composed of six judges; leading jurists from St Kitts and Nevis, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, the Netherlands Antilles, the UK and Jamaica. They adjudicate matters relating to rights of movement (people, money and business) between Caricom countries. This is the court’s original jurisdiction and is closely tied to the operationalisation of the CSME. The CCJ also can act as a court of appeal to countries who wish to use it as such. The agreement establishing the CCJ was signed on February 14, 2001, by 12 Caricom countries, and the court began its operations in 2005. This was the culmination of ideas traced back over 100 years calling for the creation of a regionally-based court of final appeal to replace the Privy Council. The first calls came from the British themselves. “When the talks about having the CCJ first started it was the judges and lawyers who had come from England and felt that people who were familiar with local conditions should have the final say on legal matters,” Sir Dennis says. “The rationale hasn’t changed. It’s just that the people who are saying it now are different.” The regional imperative The CCJ President speaks forcefully on the rationale for the Caribbean Court of Justice: “I personally believe that people should be in control of the administration of justice for their own. Going back to biblical times community leaders were selected to be judges for their tribe. Being part of a group was a characteristic of providing justice within the group.” This speaks to the notion of an independent, self-determined region with the ultimate responsibility for its justice system. But the CCJ is also crucial for regional integration. The court is vital for the functioning of the CSME, which is central to Caricom’s economic integration strategy. “The CCJ is uniquely positioned to ensure that the promise offered by this single economic space (the CSME), this further extension of our dream for a cohesive and united Caribbean region, is translated from the text of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas (which established the CSME in 2001) into a sustainable commercial reality,” Sir Dennis stated in a recent presentation. Apart from these overarching goals, he believes the court can contribute to the institutional development of the Caribbean justice system through its sub-bodies: the Caribbean Association of Judicial Officers (CAJO), the Caribbean Academy for Law and Court Administration (CALCA) and the Caribbean Association of Court Technology Users (CACTUS). These organisations, he says, “ensure that our regional judiciaries exploit a variety of avenues for technological, institutional and educational advancement.” The CCJ can also contribute to the evolution of Caribbean jurisprudence, building principles of law based on the culture, history and lived experiences of homegrown jurists. It can create judicial precedents and clarify points of law from a Caribbean perspective for Caribbean societies. One of the court’s most practical benefits is making it much easier for Caribbean nationals to access a higher court of appeal. “There are in the vicinity of 300 cases per year in Trinidad. I don’t know of any year that there are more than 10 appeals to the Privy Council. Does that mean 290 losing litigators feel they have received the best possible justice they can receive? Or does it mean that there is a sector of the community who would like to have another appeal but cannot afford to go to the Privy Council?” He adds, “We rather think there are people here who want to have another appeal and the CCJ will provide them that opportunity right here with quite a different level of expense, complexity and requirements. There is an important need for Caribbean people to have a final justice opportunity.” A social, not a political movement As it stands, all it would take to make the CCJ Trinidad and Tobago’s highest court of appeal is a special majority in Parliament. That’s easier said than done. And the story is the same throughout the region—integrationist measures stalled by political reality. But Sir Dennis doesn’t believe in blaming the leadership. “The regional governments have done a lot. All the instruments to legitimize the operations of the court have been signed. The CCJ has been funded in perpetuity. Trinidad and Tobago, for example, has already made its full contribution to the trust fund.” The time has come, he says, for civil society to make its voice heard. “When civil society stays silent it is complicit in the failures of governments. Governments have the right and duty to lead but they also have an obligation to listen to their constituents. I feel that in the case of regional integration their constituencies should assist in identifying what is in the best interest of the society.” This is similar to the approach that intellectuals like Professor Girvan and those at UWI’s Institute of International Relations have either adopted or recognised as the way forward. Integration can and should be driven by the people themselves—whether through cultural exchange, a shared sense of social justice or an intellectual commitment to positive regional development. It’s an approach Sir Dennis shared with Professor Girvan because he came of age as well during the era of that surging quest for regional identity. “We were in a colonial environment and we wanted to change it. That was something very important when we were growing up,” he says. “I think that’ something the current generation doesn’t have to face. They are not aware of what it meant to live under a colonial system.” This, the CCJ President says, was what attracted him to the advocacy side of law when he was a young practitioner, the urge to contribute to a better society, one that was more equitable, gave voice to the voiceless and reflected the aspirations of its people. So what is his aspiration for the court? He adds, “I expect that once we have a chance to operate fully that our reputation will become equal or better than the courts we admire today. When you look at the judgments we have given, we have already earned that reputation. We just need an opportunity.” Please click here to find Sir Dennis Byron’s address at the opening of the Law Faculty on April 15, 2014, and his address, “The Caribbean Court of Justice and the Evolution of Caribbean Development,” which he delivered at the 15th annual SALISES conference on April 23, 2014. |

The CCJ President, apart from his court duties, takes opportunities to speak on behalf of the Court and the broader message of Caribbean justice. A few weeks ago he gave a highly praised speech at the launch of UWI St Augustine’s Faculty of Law that focused on the ethical and advocacy role of lawyers. The day after our interview he was flying to Barbados to speak at the Annual Memorial Lecture for Barbadian national hero Sarah Ann Gill. His presentation was titled “Spirituality and Justice.”

The CCJ President, apart from his court duties, takes opportunities to speak on behalf of the Court and the broader message of Caribbean justice. A few weeks ago he gave a highly praised speech at the launch of UWI St Augustine’s Faculty of Law that focused on the ethical and advocacy role of lawyers. The day after our interview he was flying to Barbados to speak at the Annual Memorial Lecture for Barbadian national hero Sarah Ann Gill. His presentation was titled “Spirituality and Justice.”