|

May 2018

Issue Home >>

|

Sports is a multi-billion industry, spanning athleticism, big business, marketing, entertainment and legal contracts of many kinds. Sports issues that arise make headlines worldwide. From the thrill of sporting triumphs to the taint of doping scandals or the challenges of governance of hugely popular and lucrative spectator sports such as football, what goes on extends much further than the playing field. Recognizing this, The UWI Faculty of Law hosted its inaugural sports law workshop, “Lex Sportiva – Beyond the Game”, on April 12 at the Queen’s Park Oval Century Ballroom in Port of Spain. Sports is a multi-billion industry, spanning athleticism, big business, marketing, entertainment and legal contracts of many kinds. Sports issues that arise make headlines worldwide. From the thrill of sporting triumphs to the taint of doping scandals or the challenges of governance of hugely popular and lucrative spectator sports such as football, what goes on extends much further than the playing field. Recognizing this, The UWI Faculty of Law hosted its inaugural sports law workshop, “Lex Sportiva – Beyond the Game”, on April 12 at the Queen’s Park Oval Century Ballroom in Port of Spain.

Dean Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine launched the workshop, noting that the Faculty offers several new legal courses, including for the first time, sports law, to provide high calibre continuing legal education to lawyers and other professionals.

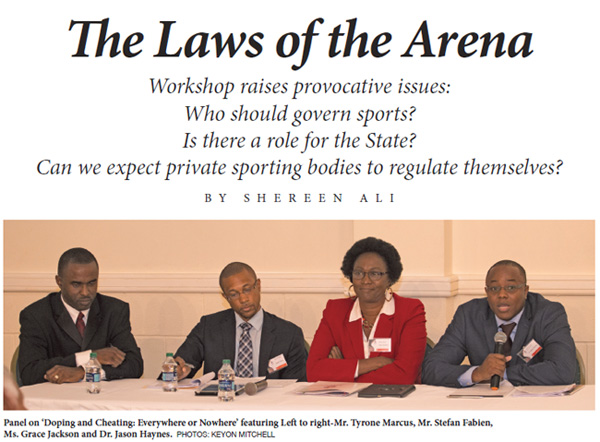

Among the presenters were British sports lawyer, author and lecturer Professor Ian Blackshaw; former West Indies wicketkeeper/batsman Deryck Murray; Dr. Jason Haynes, senior Legal Officer of the British High Commission in Barbados; Dr. Justin Koo, lecturer in the UWI Faculty of Law; Tyrone Marcus, Senior Legal Officer in the Ministry of Sport and Youth Affairs; Regan Asgarali, an attorney attached to the Intellectual Property Office of T&T; and Stefan Fabien, a corporate lawyer and member of the T&T Anti-Doping Committee.

Dr. Jason Haynes gave examples of sports cases involving many different types of law, including tort law (players, clubs, governing bodies or referees finding themselves subject to legal action for negligent liability for sports injuries), criminal law (players fighting each other, hostile fast bowling, spot-fixing/match-fixing, corruption); and contract law (the “no disrepute” clause which is frequently included in sports contracts. Players have often been penalized for violations like drinking alcohol, fighting, or the case of Mohammed Ali refusing to be in the US Army, or Michael Phelps’ three-month suspension for smoking marijuana, or the extra-marital affairs of Tiger Woods leading to the revocation of his Gillette sponsorship deal).

The workshop touched on many interesting issues, including a proposal by Dr. Koo of streaming local grassroots community sports online to make more money from local sports.

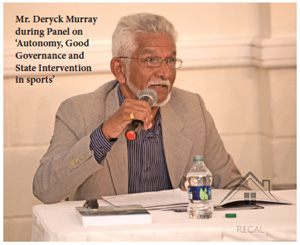

Easily one of the highlights of the workshop was the contribution of Deryck Murray during the lunchtime panel discussion. He gave some spirited and forthright opinions on the state of Caribbean sports management.

Professor Belle Antoine chaired this public discussion on “Autonomy, good governance and state intervention in sport.” She observed that in the early days, sport was not about money but about the games, and administration was done by friendly, voluntary bodies as an act of service, and by private bodies by mutual consent. But she said those days are long gone, as sport is now not just a big business, but rife with conflict.

In this context, who should govern sports? Is there a role for the State? Can we expect private sporting bodies to regulate themselves?It made for interesting debate.

Belle Antoine alluded to just a few contentious TT sports issues, such as the selection of Caribbean cricket teams, the periodic calls to fire the regional cricket board, and the case of gymnast Thema Williams, who is seeking millions in compensation for what she says is the TT Gymnastics Federation’s “harsh and oppressive” actions against her which shattered her dream of qualifying for the 2016 Olympic games.

In this context, Belle Antoine asked whether decisions by private sports bodies should be subject to review (she thinks so, for better accountability). She also asked whether we should move entirely away from the voluntary organization of major sports and create State-funded national bodies to oversee administration. In this context, Belle Antoine asked whether decisions by private sports bodies should be subject to review (she thinks so, for better accountability). She also asked whether we should move entirely away from the voluntary organization of major sports and create State-funded national bodies to oversee administration.

“All of us participate in sport; whether we play, watch, or support, we are involved, and we are passionate about it,” began Deryck Murray. He spoke of sporting ideals of commitment, dedication, and the purity of competition, with participants observing the rules and upholding the spirit of the game: “Whether win or lose, we play by the rules, shake hands with our opponents, and walk away until the next time. Those values should never change.”

But he acknowledged that those values do in fact change because money is involved.

He referred to a document from Transparency International on FIFA, and said: “FIFA is the most corrupt body in the world.” He quoted from a November 2015 document which stated that there were 209 football associations around the world, and between 2011-2014, FIFA distributed a minimum of US$2.05 million to each of those sporting organisations. Yet 81% of them had no publicly available financial records, and 85% of them published no activity accounts of what they did.

He said public sporting bodies should have financial reports, an organizational charter, an annual activity report, and a code of conduct. But as of November 2015, he said T&T had published none of those. The results of this, he said, was: “Very much the consequences for any offence committed in TT – nothing. It will be in court, and continue.”

“Sport is a global phenomenon engaging billions of people and generating some US$150 billion annually. And yet we continue a laissez faire attitude to it still,” he said.

He said that sports can powerfully influence social values, allowing people to experience great emotion, learn the importance of rules, and develop respect for others. Those at the top of sports therefore have a duty to set high standards and lead with integrity, he said.

Murray mentioned other important issues affecting sports: conflicts of interest, trading and influence and insider information, cronyism and nepotism, sale of TV rights, venue and hosting arrangements, sponsorships and hospitality, remuneration and bonuses, payments to officials, ticket sales and distribution, procurement, the role of agents and intermediaries, and elections to governing bodies. He later praised sporting bodies for continuing to have sports despite all the issues.

Murray was of the opinion that international organisations such as FIFA, the International Olympic Committee, and the International Cricket Council hide behind the “non-interference rule” as a pretext to defend national associations (or in the Caribbean case, regional federations) from legitimate demands for transparency and accountability in the spending of public resources.

“We say governments must not interfere in the running of sports. But of course, we want the government to fund every sport across the board. If my taxpayer’s dollars go to some association running sport in T&T, or in the region, am I not entitled to know what they are doing? Bodies must be answerable, whether it is to the Court of Arbitration in Switzerland, or to local courts. But they must be specific to what our circumstances, our laws are. Private bodies cannot be allowed to operate with impunity.”

He referred to the recent March 2018 cricket ball tampering scandal in the third Test Match between Australia and South Africa in Capetown in which three Australian players were banned. For him, the important thing about that was that the first meaningful call for action came from the Prime Minister of Australia – not to interfere, not to hand down a judgement, but rather to say to the Cricket Board of Australia that it had to take strong and decisive action for making Australia look like a country of cheats internationally.

In a later comment, Murray clarified that he does not advocate for a Government taking over any sport. And with regard to the role of the West Indies Cricket Board (which rebranded itself as Cricket West Indies in 2017), he commented: “When the West Indies Cricket Board registered itself as an incorporated company, to me, it has to be treated like Clico, and Clico can be treated in different territories in very similar ways under corporate law. The WICB and other sporting organizations cannot have their cake and eat it… They must be treated as a corporate body, and therefore answerable to somebody. The shareholders of the TT cricket board are the public. And now that we have the introduction of franchises, we have a maze of companies designed to obfuscate the real issues of good governance.”

|