|

November 2017

Issue Home >>

|

Like many citizens of Trinidad and Tobago I believe that the Cumuto–Toco highway can be built with minimal negative impacts on the environment. As a concerned ecologist and a PhD candidate, I believe that protecting our ecosystems is not only the responsibility of our governments, but a privilege from our predecessors, compelling us to protect and maintain our livelihoods. Like many citizens of Trinidad and Tobago I believe that the Cumuto–Toco highway can be built with minimal negative impacts on the environment. As a concerned ecologist and a PhD candidate, I believe that protecting our ecosystems is not only the responsibility of our governments, but a privilege from our predecessors, compelling us to protect and maintain our livelihoods.

The National Infrastructure Development Company Limited (NIDCO), on behalf of the Ministry of Works and Transport, is constructing the Churchill–Roosevelt Highway Extension to Manzanilla (CRHEM). This extension should eventually intersect at the site of the proposed Toco ferry port which would link Trinidad to Tobago. The proposal is for three phases: from Cumuto Junction to Sangre Grande–Ojoe Road; from Sangre Grande to Toco; and from the Churchill-Roosevelt Highway extension to Cumuto. This multi-billion dollar project has been in the making for over 11 years; hence, it would be logical to think that there has been ample time for the government to evaluate possible impacts on the immediate ecosystems, like the far-reaching ecological effects of roads through space and time.

Ecosystems are both living organisms and physical components functioning as an ‘ecological unit’. Wetland ecosystems provide food, water purification, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration and climate control. Coastal ecosystems (coral reef habitats and mangroves) complement this individually and through functional linkages. These ecosystems can be easily seen along the Cumuto to Toco road. Their functional value indicates how important a particular habitat is to a particular process, for example, mangroves and coral reefs have a higher functional contribution to primary production than seagrass beds and sand flats.

The Aripo Savanna Environmentally Sensitive Area (ASESA) is the only remaining natural savanna in Trinidad and Tobago and contains many rare flora species such as the carnivorous sundew plant (Drosera capillaris) and eye-catching ground orchids. It is the home for the sedge (Rhynchospora aripoensis) and the plant (Xyris grisebachii) which is only found in Trinidad and nowhere else in the world. It also provides a habitat for rare and threatened bird species such as; the Moriche Oriole bird (Icterus cayanensis chrysocephalus), the Sulphury Flycatcher (Tyrannopsis sulphurea) and the Fork-tailed Palm-swift (Tachornis squamata). The ASESA plays an important role as a wetland as much of its characteristic vegetation (Marsh Forests and Palm Marsh Forests of Mauritia flexuosa) provides ecological services. The carbon/nitrogen decomposition rate of organic matter in Marsh Forests is considerably higher than in semi-evergreen seasonal forests; moreover, marsh forests sequester carbon dioxide. As a matter of fact, M. flexuosa stands in South America are known to act as carbon sinks, mitigating or deferring global warming and avoiding dangerous climate change. The ASESA provides the same function, just at a much smaller scale.

Current threats to the plants and animals of ASESA include sporadic fires, hunting, poaching of the Red-bellied macaws (Orthopsittaca manilatus) and deforestation for squatting and agriculture. If these activities continue, the ASESA would no longer be capable of performing one of its most important ecological functions, which is to act as a natural sponge trapping and slowly releasing surface and flood waters.

In November 2014, we were forced to appreciate the role wetlands play in Trinidad and Tobago (in particular the Nariva Swamp) when parts of the Manzanilla–Mayaro road were destroyed due to rainfall and flooding. We are seeing ever-increasing tropical depressions and storms this year.

‘Predictions’ and ‘consequences’

The good, the bad and the ugly

The good- proper management practices together with the reconstruction of cultural concepts

It is paramount that the Government of Trinidad and Tobago commit to our environmental policies, and citizens need to work together to reconstruct old cultural concepts. The way forward could be as simple as providing meaningful information.

The bad- live for today…deal with the consequences tomorrow

Cutting through the heart of the forest is not without consequences. Let’s stop individuals from overexploiting our ecosystems and conserve the environment; by teaching individuals how to sustainably manage our ecosystems, we are advertently conserving our ecosystems for a lifetime. In today’s fast-paced society, many live for today, hence our leaders need to take the initiative of enforcing and monitoring environmental regulations.

The ugly- little policing and monitoring

If we don’t practise sustainable development, the beautiful Toco-Cumuto’s forest (and all surrounding ecosystems) as we know can be destroyed in the wink of the eye. Freeholders such as squatters, loggers and hunters can destroy our beautiful landscapes. Take our South American neighbours and the impacts from the construction of the ‘TransAmazon Highway’ in Brazil; where we see ‘loggers’ free riding on the construction of roads and the lack of legislation to exploit lumber extraction. This is a result of established squatter-communities (amongst other negative activities) which continues to further exploit the environment.

The million dollar question would be: Are we as a people ready to commit to sustainable forest management to prevent this from happening to us?

Recommendations

- Even though, engineers are using a 100m buffer zone between the ASESA and the highway, I recommend that they use an alternate route or at least increase that buffer region to 20¬0m simply because all past and present governing bodies of Trinidad and Tobago have failed to execute the full enforcement of environmental laws. I cannot recommend effective monitoring of a highway next to this sensitive area, as the risks can be disastrous.

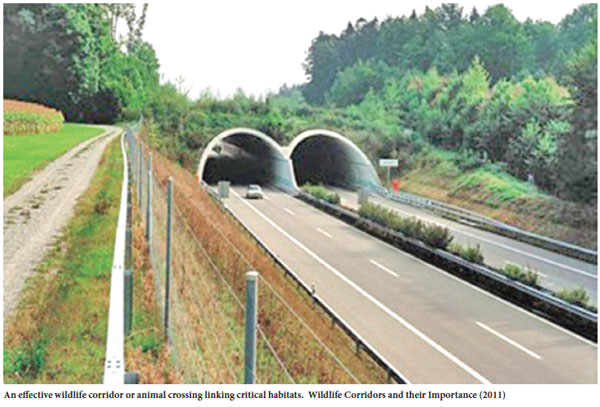

- Wildlife corridors have been effective, especially in the USA where one in every 25 accidents involves an animal. Wildlife corridors aren’t cheap, and implementing ineffective corridors simply just isn’t good enough. It’s like a taxi with a CV-1.2 litre gas engine on the hills of Paramin – bound for failure – when what is needed is a commercial V6-3.5 litre SUV.

- Wild-life fines for illegal hunting are remarkably low and should be increased. Additionally, the cost of hunting permits for seed-dispersing mammals such as the Red-Rumped Agouti should be increased in an attempt to maintain species richness within our forests.

- The Government should designate the edges of selected forest areas of the highway as mini-reserves and implement exorbitant fines for squatting (such legislation should be passed before construction of the highway), as a large number of squatters live in Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs) and compromise their functions and services.

Predictions and consequences

- If proper wildlife corridors are not implemented, Trinidad’s animal biodiversity will decrease considerably.

- If legislation is not upheld by the court in prohibiting individuals from squatting on state lands and empowering relevant authorities to stop the construction of shanty houses (*note I said ‘STOP’ and not ‘BREAK DOWN’ as individuals will not even be given a chance to build houses if daily patrols are being done). Once qualified foresters and game wardens conduct hourly patrols, illegal logging and hunting will not be an issue.

- Environmental sustainability through long-term and credible scientific research after the construction of the highway should be considered: this project should be funded by the government and spearheaded by citizens in the 13 villages that lie between Cumuto and Toco. After 10 years, the programme should aim to be self- sustaining through ecotourism.

In closing, the government of Trinidad and Tobago and its people have the ability to sustainably manage its beautiful landscapes; however, only time will tell if the ‘Cumuto-Toco highway’ would be a mortal blow to our ecosystems or an ‘Eco-Highway’.

|