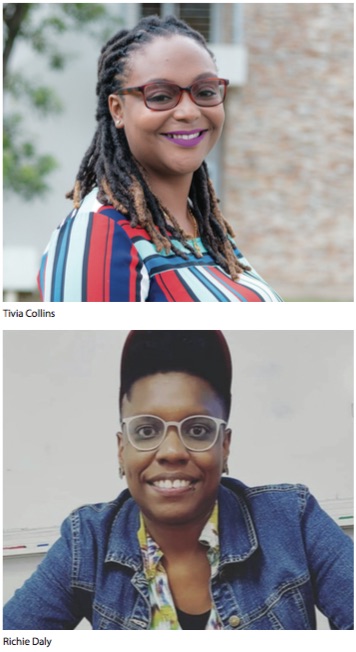

As a region, our diverse migratory history has shaped the people we are today. Now, Trinidad and Tobago faces a deteriorating crisis regarding the Venezuelan migrant community. Tivia Collins, a PhD candidate at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies (IGDS), and Richie Daly, a graduate student at IGDS, have been engaging with the community of Venezuelan migrant women here in T&T to explore their stories— in their own words.

Collins and Daly recently published an article titled "Reconstructing Racialised Femininity: Stories from Venezuelan Migrant Women".

"My work actually looks at the lived experiences of Guyanese migrant women in Trinidad and Tobago; I have always been interested in doing research on migrant women," says Collins, a migrant to Trinidad herself.

Daly, who is the child of a Venezuelan migrant, has focused their career on the experiences of Venezuelans in T&T. "I was always very cognisant of the challenges of migration," says Daly. "Getting involved, working with the migrant community and being interested in working with the migrant community genuinely came about because I am bilingual...it's in part because of the studies I've done and because of my language skills."

After seeing a call for papers in Marketing and Communications' "What's On" column (a staff and student e-update/newsletter), Collins reached out to Daly to collaborate on a piece that would delve into the real, varied and meaningful lives of the Venezuelan women in the migrant community.

"Anyone can see that what is happening in Trinidad and Tobago with Venezuelan migrants is a cause for concern," says Collins.

The two students wanted to focus on writing a piece that spoke authentically to the experiences of these women. "There is a need for a more nuanced perspective of migratory experiences, because it's easy to dismiss migrants as, oh, this is a wave of migration, using that language of multiplicity to make it seem that this is homogenous, without recognising that these individuals have their own narratives, their own experiences, their own motivations, and their own personal interests in what they want to get out of their migration experiences," says Daly.

By amplifying the voices of the 12 women who shared their stories in the project, the goal is to reposition Venezuelan women as subjects rather than objects; as, Collins says, "human beings who experience fear and joy, and who are working towards a goal of survival, which is similar to many other migrants and many other Trinidadians here."

"In the article, we talk about the horrible conditions under which Venezuelan women work in Trinidad and Tobago," says Collins. "These are not normal conditions. These conditions are based upon, unfortunately, their migrant status and their gender. We wanted to position the realities vis-a-vis the posts that you see on social media for example, comments about Venezuelans coming to ‘take things', when in fact, they are here, as we all should be allowed to, to make money to provide for their family, which is a basic human need…. It is about the economics of it; it is about eating. And as a country, Trinidad and Tobago should not, culturally, politically or economically stop people from eating, even if they weren't born here."

Daly says, "It's really easy to talk about a ‘migratory outflow', a ‘wave of migration', and not recognise that each individual in that supposed ‘wave' has their own life story, their own familial connections, their own loved ones, their own personal motivations, and even their personal desires."

One of their intentions with this work is to change the type of conversation surrounding this crisis and honour the personhood of the people at the centre of it. With visibility comes safety and reduction of harm, and highlighting these personal narratives is part of a much-needed effort to protect and uphold human rights and dignity.

For Daly, the incentive is also to reframe the migratory relationship between Venezuela and Trinidad—one that has existed in many forms since humans have inhabited both landmasses:

"This is not the first time Venezuelans have migrated to Trinidad, or Trinidadians have had to interact with Venezuelans, be it here or in Venezuela. That is something I want to work on - historicising Venezuelan migration. I just want to continue to honour their stories, their perspectives, and honour their understandings of their situations, because as much as I have ties to the community, I am not the community."

"We have some recommendations after doing the research," says Collins. "First being that the government of T&T implement a migration policy that guarantees the rights of migrants, particularly in vulnerable situations. Trinidad and Tobago signed the UN's Refugee Convention and Protocol in 2000 but has not put anything legally up to this point that allows refugees to seek protection from prosecution in a blanket way. Trinidad considers requests on an individual case-by-case basis. When you have mass migration happening in your country, that is not going to work. Also, there has to be local legislation on asylum-seeking and refugees. It does not exist currently. We recommend that there be a formal system that allows Venezuelans to legally live and work in Trinidad and Tobago beyond the one-year work permit that was granted last year and now has expired, with no system in place that allows for renewal."

She adds, "we encourage training at the level of immigration officers and police officers, which allows them to understand how to address Venezuelan migrants, especially Venezuelan migrant women, who are particularly vulnerable because of their socioeconomic status and their gender. Finally, one of the big things for us is—how do we address xenophobia and xenophobic sentiments across the country? I do believe that there may be some knowledge passed down when there is visibility."