|

October 2015

Issue Home >>

|

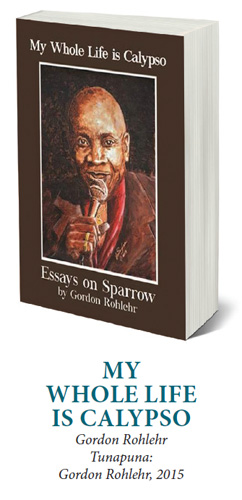

In his Author’s Preface, Gordon Rohlehr describes “My Whole Life Is Calypso” as “my personal tribute to Sparrow for his eighty (80) years of residence on earth and his sixty (60) years of affirmative performance of calypsos.” He also considered it “a sample of my contemplation of the career of one of the region’s premier and most celebrated artists,” and advises that the book comprises basically “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” his latest essay, and “Sparrow and the Language of Calypso,” his first essay. It includes as lagniappe “Sparrow as Poet” and “Carnival Cannibalized” and ends with the citation he prepared for CARICOM in 2001 “when they endowed Sparrow with the region’s most prestigious title: Order of the Caribbean Community.” In his Author’s Preface, Gordon Rohlehr describes “My Whole Life Is Calypso” as “my personal tribute to Sparrow for his eighty (80) years of residence on earth and his sixty (60) years of affirmative performance of calypsos.” He also considered it “a sample of my contemplation of the career of one of the region’s premier and most celebrated artists,” and advises that the book comprises basically “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” his latest essay, and “Sparrow and the Language of Calypso,” his first essay. It includes as lagniappe “Sparrow as Poet” and “Carnival Cannibalized” and ends with the citation he prepared for CARICOM in 2001 “when they endowed Sparrow with the region’s most prestigious title: Order of the Caribbean Community.”

Essentially, the book proposes these two questions: “What has Sparrow… given to Calypso over his six decades of journeying between worlds, publics, audiences and homelands, and what has Calypso done for Sparrow in return?” In addressing these issues, Rohlehr covers Sparrow’s 60-year engagement with his homelands and places of residence and performance, especially Trinidad and Tobago which has provided inspiration to launch the Birdie into orbital flight and simultaneously the challenge to bring him crashing back to earth.

The literary quality of “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” is enhanced by the fundamental underlying unity of the themes discussed throughout the essays and by the omnipresence of the bird motif. This draws from Sparrow’s self-description as a “bird flying from tree to tree” taken from the early calypso “Sparrow is a bird.”

Rohlehr suggests that while in its original context it referred to Sparrow’s irresponsible freedom to enjoy sexual escapades, it may have deeper implications and can apply to the restless journeying and performing which characterized Sparrow’s life and career. Some of the pivotal discussion points in “My Whole Life Is Calypso” echo some of the thoughts published previously in “Sparrow and the Language of Calypso” “Sparrow as Poet” and “Carnival Cannibalized.” For one thing this can excuse – if not properly explain – Rohlehr’s reference to “Sparrow as Poet” and “Carnival Cannibalized” as lagniappe; for another, it may require the reader to re-read the essays in their order of original publication to appreciate the development in Rohlehr’s thinking.

In “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” Rohlehr’s deeper engagement with issues raised before transcends what he sometimes calls ruminations and musings, and emerges as a complex of interrelated philosophical disquisitions. To give one example, in the essays before “My Whole Life,” Rohlehr consistently muses about Sparrow’s problematic relationship with the different spheres of Trinidad and Tobago society. This musing is taken to another level in “My Whole Life” where he wonders whether “the necessity Sparrow as entertainer and performer has faced to communicate with so many different audiences and publics, do not result in a state of permanent transitionality in which identity becomes performance and the audience’s indifference to or rejection of performance is received as a deadly blow to identity, to centre-self.” This business of locating self within space and time, although present in differing degrees in the earlier essays, is central to “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” which focuses on the psychology of Sparrow rather than his art, which was the principal subject of “Sparrow and the Language of Calypso” and “Sparrow as Poet.” Here, too, one can see a development – or better – a change in focus in Rohlehr’s thinking viz-a-viz Sparrow.

“My Whole Life” zooms in on the psychology of Sparrow’s performance of identity: “for Sparrow character, ability and reputation became interchangeable components of a single personality…” Again and again Rohlehr interprets Sparrow’s songs and controversial behaviour over 60 years as manifestations of his essentialist problematic: this desire to take flight away from Trinidad and Tobago measured against the need for affirmation from the very society.

Rohlehr interprets his inclusion of “Congo Man” and the somewhat less controversial “Marajhin” in his set after he received the Order of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the nation’s highest award, as him calling the bluff of unnamed individuals and groups.

Rohlehr accords Sparrow, whose “main theme had become himself and the recurrent phenomenon of survival,” the mythic status reserved for heroes and demigods. “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” accords Sparrow the highest form of respect by first submitting his work to academic rigour and then by acknowledging the heroic dimension to his persistent struggle to affirm his rightful place in time and space.

“My Whole Life Is Calypso,” which has been 46 years in the writing, is emblematic of the sterling quality of vision and expression that has earned Rohlehr, Emeritus Professor of West Indian literature at The UWI, the acclaim of architect of literary criticism on the Calypso.

Taken together, the book’s five essays constitute the distillation of a literary scholar’s meticulous examination of the technical artistry and psychology of The Mighty Sparrow; it also crystallizes the thoughts of the celebrated scholar who has, from a distance, watched Sparrow “[resurrect] himself decade after decade amidst paradoxes of acclamation, censure, glorification, nullification and the underlying reality of time, aging, and diminishment." Rohlehr readily acknowledges that his first essay “Sparrow and the Language of Calypso” “helped define the terms of my interface and engagement with the Trinidadian and Tobagonian for the next four decades,” the collection “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” testifies in part to this interface and engagement.

Tweaking a David Rudder phrase, I can say with reference equally to Sparrow’s career and “My Whole Life Is Calypso,” surprisingly the only full-length academic study on him, “It doesn’t get better than this.”

Dr Louis Regis was Head of the Department and Senior Lecturer - Literatures in English, in Literary, Cultural & Communication Studies until his recent retirement from the UWI. |