|

|

|

|

October 2018

|

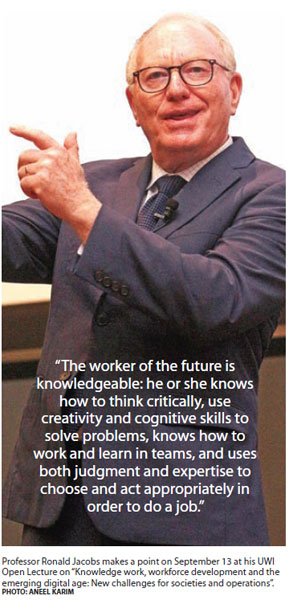

By Shereen Ann Ali. Sometimes, as fast as you train people for one job, the very nature of the job (or the industry) changes, and you need to re-train people in an entirely different kind of way, sometimes for entirely different kinds of work. Such is the dizzying rate of change in the workplace today, where technology is revolutionizing many processes, and where people can no longer rely on lifelong employment doing just one rote job forever. Things change, sometimes rapidly, and employees may find themselves casualties in obsolete jobs or dying industries unless they adapt or retrain for new kinds of work. This was just part of the message shared by Professor Ronald Jacobs last month when he gave the Distinguished Open Lecture at The UWI St Augustine campus on the evening of September 13. Human Resource professionals as well as curious members of the public flocked to the Daaga Auditorium to hear him speak. Jacobs is Professor of Human Resource Development at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a leading scholar in his field. He previously worked at Ohio State University where he is Professor Emeritus, and he is the principal of RL Jacobs & Associates, a global consulting firm. Prof Jacobs did an early first degree in Film Studies and English Literature in 1973 before studying for a doctorate in Instructional Systems Technology at Indiana University some years later. Since then, his career has been focused on human resource and workforce training issues, and he has been called the world’s subject matter expert on structured on-the-job training. He has authored or edited six books on human resource development, and is working on a new book on work analysis (documenting what people do in their jobs), due out in 2019. His talk at UWI on “Knowledge work, workforce development and the emerging digital age: New challenges for societies and operations” touched on some of the huge industrial and technological changes sweeping through societies, requiring new answers to some core questions about what we train people for, how organizations provide learning to boost workplace performance, how to “manage planned change” to help individuals adapt; and how to support workers and their families facing the disaster of job loss. A widely travelled man, Jacobs has visited South Korea, China, Saudi Arabia and other parts of the world to talk about workforce training issues. Jacobs began his Open Lecture presentation at The UWI, Trinidad, by mentioning some major world events he remembers living through: the 1968 domestic strife in the US, with students protesting American involvement in the war in Vietnam; the June 1989 protests of Tiannamen Square, where Chinese students demonstrated in Beijing for a freer, more equitable society; and the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Such events became widespread knowledge in an increasingly globalized world where mass media and the impacts of industry were creating unprecedented connections among people and markets, he said. By 1989, the world was becoming more open than it had ever been before, with far fewer barriers, he said. Jacobs noted that big social and economic changes happened especially after 1989 due to a combination of factors including globalization, technology (especially the rise of Information Communications Technology), the “new economy” of “free markets” and cost/price pressures, political legislation and partnerships, changing demographics, and the volatility of work, which has seen a move from stable jobs to sometimes no job stability at all. Jacobs took a moment to share a story of profound change affecting the small town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the place where he himself was born in 1951. A place with lots of water, coal and transportation routes, in the 1950s and 60s Johnstown was a steel town, with more than 30,000 of its people working in the steel industry and having stable jobs there. But by 1977, Bethlehem Steel had closed its Johnstown plant, and by 2000, less than 2,000 local people worked in the steel industry. It was a crushing experience for thousands of people, often members of close-knit families who had all once depended on the steel mill for their jobs and security, but who found themselves unemployed. In 2001, Jacobs indicated the unemployment rate in Johnstown was still 12%. By 2008, the first wind turbine manufacturing facility had opened. But Jacobs said by 2015 the town was still working on its transition from the “Rust Belt” to the “Health Belt.” The concept of “workforce development” was not on anyone’s radar in the US for the longest while, said Jacobs. There were no partnerships between the public and private sectors; they each did their own thing. Not until 1990s did people decide to start using public monies to think about “workforce development”, a term the US Federal Government started to use. One definition of workforce development is: “The coordination of public and private sector policies and programmes for the purpose of providing individuals with the opportunity to achieve and maintain a sustainable livelihood for the benefit of themselves, employers, and society as a whole.” (H. Jacobs and J. Hawley, 2007, Emergence of Workforce Development). But what does the term really mean? It is a collaboration of stakeholders in society with a focus on employment, said Jacobs. Jacobs said the core issue here is: How do you prepare individuals to enter the workforce? He then spoke about various training avenues, including post-secondary vocational education; dual work-learning systems; government training programmes and universities. He spoke briefly of occupational analysis, and the notion of National Occupational Standards which some (not all) countries have established. Germany, the UK and Korea have national workforce approaches with standards set for different occupations, whereas the USA does not (individual USA states have their own approaches, but it is not national). You can’t make an advanced society by workers doing simple, repetitive tasks, said Jacobs, as he launched into the whole concept of “knowledge work.” The worker of the future is knowledgeable: he or she knows how to think critically, use creativity and cognitive skills to solve problems, knows how to work and learn in teams, and uses both judgment and expertise to choose and act appropriately in order to do a job. Jacobs noted that “knowledge workers” are not any exclusive set of people: anyone today might be called on to do “knowledge work.” The term simply refers to the ability to troubleshot and solve problems, facilitate work processes, critically analyze situations, and make appropriate decisions, among other qualities, he said. Jacobs observed how the world has moved from the mercantile age to the factory or industrial age, to where we are now: the digital age (also called the computer or information age). He spoke of the need for continual workforce planning and training as conditions change. And at one point, in the public question session, there was the comment that despite the changing nature of jobs and industries, “You can’t worship profits and throw away people.” |