Many of us have a family elder – perhaps an uncle or a grandparent – who knows trees. They can name them. They can give the lore surrounding them. They can tell you the home remedies of which they are ingredients. That knowledge is dying.

“When I ask people about trees, they know hardly anything,” says Linton Arneaud. “I cannot blame them because they were not exposed to that knowledge. But think about it. Think about your grandchildren. If we continue the way we are, they won’t know anything about trees.”

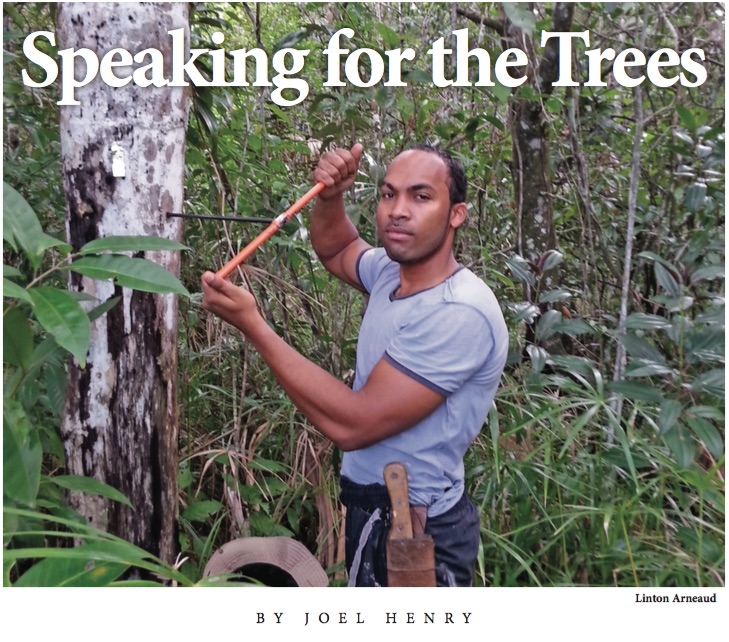

Arneaud however, knows a lot. An environmental biology PhD candidate and teaching assistant in the Department of Life Sciences, he is extremely passionate about plants – trees in particular.

“I guess it’s just a natural calling,” he shrugs.Speaking to him is like being transported into a green realm where the society is made up of trees and plants and marshes. He’ll walk you over to the trees in your vicinity, trees you haven’t given a second thought, and explain their lineage (phylogeny) and the magic of their existence.

“I grew up in the country, Rio Claro,” Arneaud says. “As a child, I would be involved in all sorts of outdoor activities – fishing, camping and many other things. And all the trees and plants put questions in my head.”

He wanted to learn about the green world he inhabited. This led him to become a scientist. Since then he’s earned his degree in environmental and natural resource management (with minors in biology and marine biology). His PhD work is focused on the moriche palm, a wonder tree with many uses (including ecological) that is indigenous to Trinidad and South America.

A flowering yellow poui tree at Signal Hill Road, Orange Hill,

A flowering yellow poui tree at Signal Hill Road, Orange Hill,But with that knowledge has come great concern for our natural environment and native trees.

“We have to understand that in the cycle of life, trees come before animals. Plants are simpler organisms, and they photosynthesise, creating oxygen. This oxygen is what we need to survive. If you don’t take care of the trees, ‘too late, too late’ will be the cry and we will suffer the loss of their ecosystem services,” Arneaud says.

“We have to understand that in the cycle of life, trees come before animals. Plants are simpler organisms, and they photosynthesise, creating oxygen. This oxygen is what we need to survive. If you don’t take care of the trees, ‘too late, too late’ will be the cry and we will suffer the loss of their ecosystem services,” Arneaud says.

The moriche palm is a prime example. Used for everything from food colouring, to medicine, to wine and even sexual enhancement for women (“not scientifically proven” he says about this last one), in Trinidad it serves important ecological functions. The palm provides natural floodwater retention, replenishes aquifers, and purifies water. And it only grows (naturally) in six areas in Trinidad.

Local (not localised - many trees, such as the pink poui, silk cotton and water immortelle, that we think are indigenous are really well-adapted imports) trees are cheaper to maintain, more resistant to disease and have adapted to our unique environment for thousands upon thousands of years. Why are they at risk? The easiest answer is deforestation. But deforestation is not the only threat. Imported trees such as the acacia are also a danger.

“It’s an invasive plant from Australia,” says Arneaud. “We are planting the tree alongside buildings, highways and within commercial developments. It is going to reproduce. It is going to go into our forest edges, and it will dominate our species. And then we will have real problems. Our species will be displaced.”

Why would developers and planners use acacia? Because they don’t know the risk. And this brings us back to the beginning. We are losing the knowledge of our trees.

“In 1946, Dr John Stewart Beard and fellow botanists identified a total of 384 species of trees in Trinidad, by the late 90’s, only 130 tree species were known by naturalists (Quesnel & Farrell 2000). Today, this list has dwindled even further to well below 100 persons being able to identify native trees,” he says.

Arneaud is on a mission to teach the public about local trees and sensitise them to the risks they face. He has written several articles (one published earlier this year in UWI Today https://sta.uwi.edu/uwiToday/archive/ march_2019/article13.asp) and intends to do much more.

“Last year, I won a scholarship to study tropical biology at Florida International University. That added yet another layer to my love and passion for plants,” he smiles. “But it also showed me I need to get this information out.”

Arneaud is planning to specialise in grasses, as he sees the need for a grass specialist (agrostologist) in the country. He believes the ecological service grasses provide (soil stabilisation and protection) will be of great importance in the near future.

He adds, “we have to make sure that 100 years from now they don’t have a tree in a museum and say ‘this is what a tree looked like’.”

You can meet Linton Arneaud (and other experts in animals and microorganisms) at the 2019 Bioblitz event, which will take place at the Tabaquite Secondary School on November 2 and 3. For more information please visit https://www.facebook.com/TandTBioblitz/.

A flowering hogplum tree at Tabaquite Road in South Trinidad.

A flowering hogplum tree at Tabaquite Road in South Trinidad.