|

|

|

|

September-October 2010

|

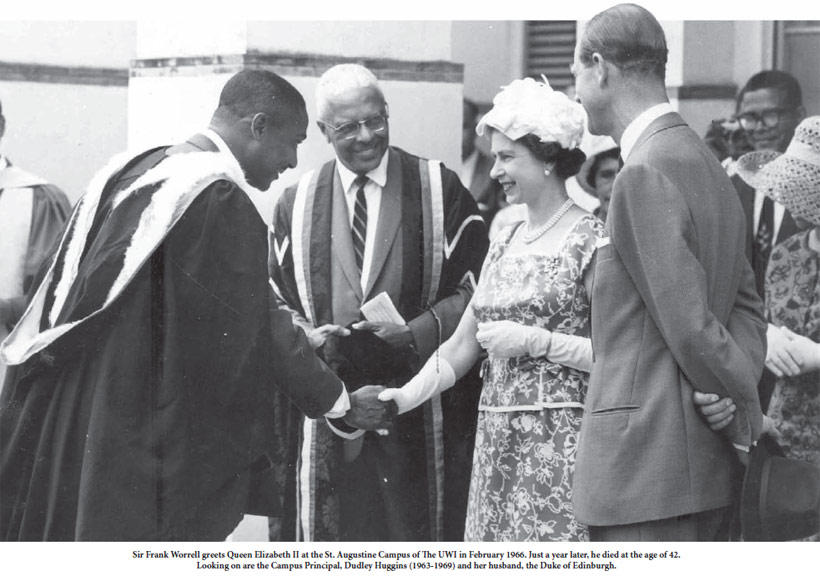

Sir Frank Worrell and CLR James: Once in a blue moonThis is an edited excerpt of a speech by Vaneisa Baksh at a function to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Sir Frank Worrell becoming captain of the West Indies cricket team in 1960. The event was organised by the Sir Frank Worrell Memorial Committee and took place on September 8, 2010 at the Central Bank Auditorium, Port of Spain. Sir Frank Worrell was a warden at The University of the West Indies. Technically, Worrell was not the first black captain of the West Indies, George Headley had captained a match in 1948, and even Learie Constantine had acted briefly as captain during a match in 1935 when Jack Grant injured his ankle on the fourth day. But he was the first to be appointed captain for a series, and it came after considerable lobbying by CLR, because the West Indies Cricket Board of Control was set to re-appoint Gerry Alexander to lead the Australian tour of 1960-61. Worrell, as one of the legendary three Ws, which included Clyde Walcott and Everton Weekes, who had already established their status for a decade, was thought the best qualified for the position. In 1958, CLR returned to Trinidad after 26 years outside, and became editor of the People’s National Movement party’s newspaper, The Nation. He used its pages to make his case, which was partly, in his words, an “attempt to dislodge the mercantile-planter class from automatic domination of West Indies cricket.” “Alexander Must Go,” was the headline of one piece insisting that the very idea of Alexander captaining a side including Worrell was “revolting.” “The best and most experienced captain should be captain, what has the shade of one’s skin anything to do with it?” CLR systematically laid out Worrell’s qualifications for the post. In England in 1957, he said, “His bearing on the field, all grace and dignity, evoked general admiration. In every sphere, and others beside myself know this; the opinion was that he should have been the captain.” In The Nation of March 4, 1960, he famously wrote, “Frank Worrell is at the peak of his reputation not only as a cricketer but as a master of the game. Respect for him has never been higher in all his long and brilliant career.” He said Australia wanted him. “Thousands will come out on every ground to see an old friend leading the West Indies. In fact, I am able to say that if Worrell were captain and Constantine or George Headley Manager or co-manager, the coming tour would be one of the greatest ever.” He cited tours to India with Commonwealth sides in the 1940s, where Worrell, who captained the team on three occasions, was esteemed as “one of the greatest cricketers of the age.” Incidentally, those tours comprised multi-national teams, which had never before been seen, but is now the norm in Twenty20 tournaments of today. CLR waged a relentless campaign, and the outcome was that Frank Worrell was appointed captain for that series, which reconfigured the way the game was played and which saw a new captaincy paradigm for the West Indies. After a dozen white captains, Frank Worrell came, and fifty years of West Indies Test cricket have now gone by without another white face leading the team. We’ve had 17 or so captains since, although the number of times the captaincy has been changed is a bit more, with some serving more than once. But we haven’t had another white captain, and the emergence of Brendan Nash is the first time in a long time that there has even been a white player on the team. Have our white players retreated? Dismissed the game? Or have they been wilfully excluded? Why that is so, is a matter for a different discussion. Why CLR took up cudgels for Frank Worrell is more pertinent here. CLR perceived his ideal qualities of leadership in Worrell. I’d like to focus on them because it is important to know what they were or else Worrell’s identity becomes shadowed and all that our future generations will know is that Sir Frank Worrell is the name on a building. From as early as 1933, when he published The Case for West Indian Self-Government, CLR was setting out what he thought to be a West Indian identity. In a 1967 article for The Cricketer, called “Sir Frank Worrell: The Man Whose Leadership Made History,” he painted this portrait of Worrell. “If his reserve permitted it, this remarkable intelligence could be seen in his views of West Indian society. To us who were concerned he seemed poised for applying his powers to the cohesion and self-realization of the West Indian people. Not a man whom one slapped on the shoulder, he was nevertheless to the West Indian population an authentic national hero. His reputation for strong sympathies with the populace did him no harm and his firm adherence to what he thought was right fitted him to exercise that leadership and gift for popularity which he had displayed so notably in the sphere of cricket. He had shown the West Indian mastery of what Western civilization had to teach. His wide experience, reputation, his audacity of perspective and the years which seemed to stretch before him fitted him to be one of those destined to help the West Indies to make their own West Indian way.” They were the makings of the leader CLR felt was necessary at the time, but his was not blind loyalty to Worrell. He was concerned with what he felt was best for the game. In the course of my research on West Indian cricket, I came across a document which had never been published, and which is included in my thesis. Written by CLR in 1961, following the celebrated tour of Australia, it was called “After Frank Worrell, What?” and it raised several issues about how to sustain West Indies cricket and its cricketers. As forceful as ever, CLR began, “I am absolutely and militantly opposed to Frank Worrell being made captain of the 1963 team to England.” Arguing that not only had Worrell indicated he did not want to do it as he felt he was not fit enough anymore, James insisted that Worrell had already shown the world all the qualities it needed to see, and it was time to let Conrad Hunte take up the mantle. “Worrell has shown what we are capable of. He had to wait a long time. The English people know all about Worrell now. He can add nothing to our and his reputation. But he can lose a lot of both.” He suggested that he go in another capacity. “Send Frank as manager; send him as special correspondent for the West Indies press; send him as Ambassador or Special High Commissioner to the Court of St. James. But not as 1963 captain, thank you.” We know that Frank went to England, and that series would be the last one of the three in which he captained the West Indies. He had led for 15 matches against Australia, India and England, won nine, lost three, tied one, and drew two—and for those of you interested in statistics, he had a 60% win record, as compared with Clive Lloyd’s 48.6% and Viv Richards’ 54%, or Steve Waugh’s 71.9%, and even Gerry Alexander’s 38.8%. In that short time he had done more to alter the international game of cricket and the way players saw it and themselves. In the 1970 book John Arlott edited, Cricket: The Great Captains, James wrote of Worrell, “I was amazed to find that his main judgement of an individual player was whether he was a good team-man or not. It seemed that he worked on the principle that if a man was a good team-man it brought the best out of him as an individual player.” Worrell was an exceptional manager, and a major aspect of this was his insistence on fair play, on the field and off it. He was an egalitarian, and in his resolute and diplomatic way, commanded respect for his beliefs. Worrell’s emergence at the time of the nationalist movement in the English-speaking Caribbean singled him out. For a time he was known as a cricket Bolshevik, following his letter to the West Indies Cricket Board of Control before the 1948 tour of India to negotiate payment, and to work out the continuation of his league cricket in England during the summers. The Board refused to discuss the matter, fully expecting that he would back down. He did not, and opted out of the tour, making a statement that cricketers too were professionals and should be treated with due respect. So you see, Worrell stood on the side of players when it came to Board negotiations. The great bowler, Wes Hall refers to the nurturing quality of his leadership in his autobiography, Pace Like Fire: “Even when Gerry Alexander was skipper it was Frank who solved every player’s problem, negotiated his league contract and advised on his play.” It was within this concern for players’ welfare that Worrell stood up to inequitable systems of remuneration. Worrell also helped to foster a mentoring programme by dismantling the practice of senior players remaining aloof from the newcomers. “Normally junior members of any touring party automatically refrain from mixing with the experienced Test players, partly because they are overawed by them, but Worrell and Gaskin wiped away this distinction,” wrote Hall. There is also the little known story of Roy Marshall, of whom Michael Manley wrote, “there are those who think that Roy Marshall and Gordon Greenidge, both Barbadians, may be the two most accomplished openers the West Indies ever produced.” In his autobiography, Test Outcast, Marshall talked about privilege and prejudice, “Being a white West Indian myself, the son of a planter and living a fairly sheltered life, I suppose I did grow up with slight racialist feelings.” He goes on to say, “As a result of my fair skin I was able to enjoy membership of special clubs, make use of special privileges which are not enjoyed by the coloured people. I was brought up in an atmosphere which gave the impression that the white man was superior.” He wrote that these feelings were altered through his interaction with Frank Worrell, who was not yet captain, but whose leadership qualities were so evident that the younger players naturally looked to him for guidance. “I lost all such feelings and impressions when going on tour–and the man I have to thank most for this was Frank Worrell. When I started touring I was only nineteen and Frank was six or seven years older. He had already travelled fairly extensively and knew the way of the world. He held no such views. To him every man was entitled to equal consideration, whatever the colour of his skin. Being around with Frank and seeing how he treated everybody, you could not help but come to the same conclusion.” These were some of the characteristics of Sir Frank, qualities that made him an excellent leader. They are qualities not generally associated with contemporary leadership inside or outside of West Indies cricket in recent times; but to me they are worthy of emulation even as we acknowledge that West Indies cricket no longer represents a model of excellence for this generation. There were many similarities between CLR James and Sir Frank Worrell, and perhaps this further aligned their fates. They believed in West Indian-hood and were federalists to the bone; yet they were both maligned in their home countries for being too arrogant and outspoken, and had to live elsewhere. They were well-read and had both been newspaper columnists in England. There was yet another compelling bond. All who saw Worrell, remark on the beauty and grace of his movements, the polish of his manners, the elegance of his dress and deportment, and his almost languid ease in any social circumstance. CLR, himself an artist, analysed everything through a lens that was perpetually seeking the crafting hand of art. In Worrell he found the perfect subject. For Sir Frank Worrell was nothing short of a work of art, and CLR was a connoisseur. |