|

|

|

|

September 2011

|

The joiner of dotsBy Kenwyn Crichlow

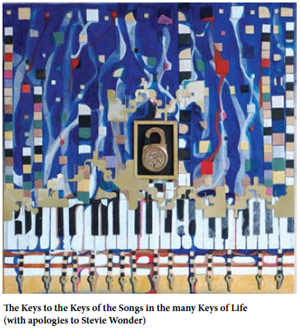

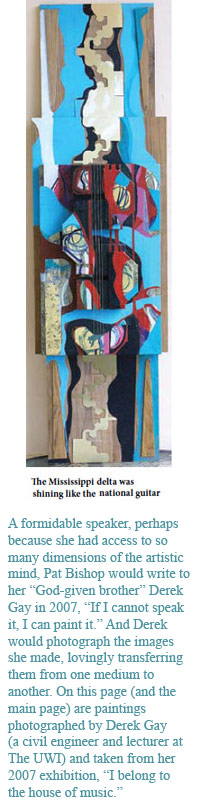

Her painting connects to the music rehearsal process. It was her way of discovering Shubert’s intentions, painting informed her searching for the ways his music may be conveyed in the connections between Eddie Cumberbatch the tenor, and Lindy-Ann Bodden-Ritch the pianist. She knew this collaboration between instruments, people, musical score and perceptions of an audience was key to “joining the dots” in musical performance as painting is to drawing out the possibility of a form in art. Painting was her private practice, in the sense it activated a space at the heart of her artistic practice. It provided the inner point from where her wide ranging cultural work was to do everything and more than that everyone wanted her to do. She thought it was her responsibility to Beryl McBurnie that the Little Carib Theatre return as an outstanding performance space. She knew it was her official duty to work with Ministerial committees; to supervise academic research at the Carnival Institute and the Department of Creative and Festival Arts. It was her pleasure to make music with the Desperadoes and Exodus steel orchestras, especially to sit in the “engine room” knocking her cowbell to get players to hear themselves. She assumed that it was her responsibility to provide the best examples of world musical heritage to the Lydians, as well as I had a long association with Pat Bishop, not as long as Robert Las Heras or Peter Minshall or Jackie Hinkson or Leroi Clarke; I met her during her time with the Solid Waste Company. She was the driving force of the public education campaign to clean up Trinidad and Tobago. Everyone was familiar with her ‘Charlie’ character. She acknowledged that for a little time “Chasing Charlie away” entered the public attention and animated a genuine concern for the physical state of the surroundings. I first met and co-opted her into a committee to recover public interest in the Trinidad Art Society. The ensuing event at the Tent Theatre on the same day Maurice Bishop died was an inspiration for her painting of the Grenada Trilogy. A three-panel mural. I remember her tears of sadness in the central panel, the “thirty pieces of silver”, which addressed the tragedy of political betrayal. In that moment, she felt free to unburden herself; “painting is too hard”. Her recent sad, but unsurprising death awakens a memory of her interpreting Boogsie Sharpe’s “Pan Rising” music and me taking the painting opposite onto the neighbor’s fence so that he could see the crescendo in the shape of her painting. The Pat Bishop of a few weeks ago was no different, incisive and profound. The mural size of her earlier paintings has come to whatever she could make on the table she constructed over her bed. I wryly joked it was “her last”, in the sense of a cobbler’s workbench from where she painted, wrote, read, ate, met, planned, phoned, rehearsed and counselled so many persons. It was from there she created the collection of paintings she named "She sells on the sea shore". We spoke of comparisons between this collection and an earlier show in Barbados. She was anxious not to be thought of as doing the same thing again. She was not; this upcoming presentation was full of her memories. I observed this in her process of long introspections about her growing up with Gillian, Ena and Sonny in Woodbrook, her happy days at Tranquillity School and riding to Bishop Anstey High School, learning oil painting from sessions with Cicely Forde, her meeting with Billie Miller of Barbados in northern England. She was a source of information about art history, Caribbean politics, Gillian’s designs, the disposition of pianos and personalities from all over the region. She was quite brutal in the review of her work. I have watched her eviscerate perfectly reasonable paintings. She never let up on herself, always questioning her expectation of how a painting should look or how it was to be seen. Pat felt a strong affinity between her art and the heritage of mas-making: she connected her practice of “a thing well-made is a thing worth making” to the work of dress-makers like her mother, Meiling and Claudette from Laventille. She was uncommonly adept at seeing relationships between art, writing, speaking, music, cooking, penmanship and nearly everything else. She wanted her work to look outward, but never too far inward. Art was for people to see reflections of themselves. She knew that her birth in Woodbrook and life as artist was to reach out to others – in her last days, even as her soul seemed to be weighed down, terminally exhausted. She persevered to live up to the expectation of a “cultural icon”. Some have wondered why, given the many ways those in ‘authority’ could ‘dumb-down the place” without even raising a sweat. She never answered. She dreamed instead of curating an exhibition of the art and designs of the several graduates of the Visual Arts course of The UWI. She imagined their work could be the best celebration of our 25th anniversary within the national 50th anniversary of Independence at the renovated Museum of Port of Spain. She thought that the national community needs to know more of our graduates. I agree. Kenwyn Crichlow is an artist and a lecturer at the Department of Festival and Creative Arts, The UWI, St. Augustine. |

“I need you to look at these paintings and talk to me about what I am doing. I need a crit,” Pat said a few weeks ago. She was preparing for the Schubert’s Winterreise production.

“I need you to look at these paintings and talk to me about what I am doing. I need a crit,” Pat said a few weeks ago. She was preparing for the Schubert’s Winterreise production.  to listen to Robert Greenidge, Boogsie Sharpe, Raf Robertson, Hyacinth Nichols and whoever was making sophisticated music. This inner point was also a departure into a seclusion in which she felt most vulnerable. For example, I knew she would ask Leroi Clarke to look at her paintings, but never on the same day that I was expected. Two critical opinions would be too much bruising.

to listen to Robert Greenidge, Boogsie Sharpe, Raf Robertson, Hyacinth Nichols and whoever was making sophisticated music. This inner point was also a departure into a seclusion in which she felt most vulnerable. For example, I knew she would ask Leroi Clarke to look at her paintings, but never on the same day that I was expected. Two critical opinions would be too much bruising.