Death of a Revolution Death of a Revolution

FILM REVIEW

DEATH OF A REVOLUTION

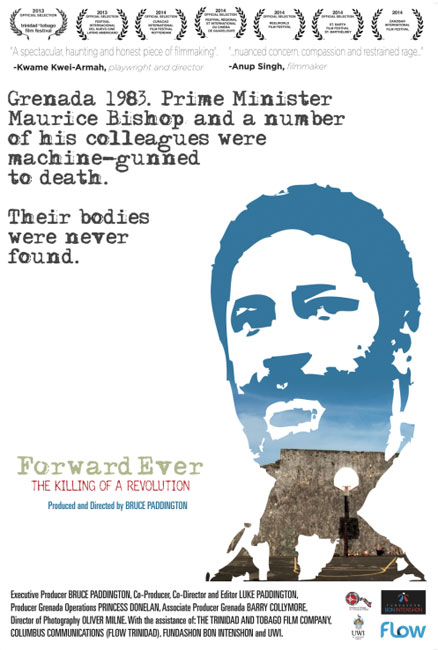

Forward Ever: The Killing of a Revolution

Documentary (2013)

Bruce Paddington

By PAT GANASE

In this documentary, Bruce Paddington assembles an impressive cast of Grenadians, and selects from miles of footage to tell the story of the rise and fall of the Grenada revolution. From 1979 to 1983, the People’s Revolutionary Government engaged Grenadians in a bold Caribbean experiment. It lifted Grenada and Grenadians to the world stage. Perhaps it was too bold for the world. In hindsight, it may have been fated to fall in a manner swifter than its rise. To this day, the brutality of its demise confounds the people we believe ourselves to be, as Caribbeans.

This retelling – almost 30 years after the event – is important for Grenada as it is for the other states in the Caribbean archipelago. Trinidad and Tobago lies just 90 miles south west of Grenada; and most of us know little about what was happening there in the early 1980s. We did wake up to the US invasion of Grenada in October 1983. Then, Grenada reverted to Caribbean island as location in Heartbreak Ridge with Clint Eastwood; that film was not about Grenada at all.

Paddington’s Forward Ever: The Killing of a Revolution – released in 2013 – positions this Caribbean experiment for critical consideration and possible learning. It is an important point of departure: public viewing and discussion that might lead to deeper understanding. There are no actors in this docudrama of just two hours. None are needed. The narrative is sequential and simple. Most speakers are straight to the camera, unapologetic. The truth shines. In the first half, we witness the blossoming of Grenada, extricated from two decades of the personal fiefdom and oppressive control of Eric Arthur Gairy.

The New Jewel Movement was formed in the early seventies to oppose Gairy, whose Mongoose Gang harassed them at every turn. In 1973, Rupert Bishop – father of Maurice – was killed. It was learned that Gairy had planned to liquidate the leaders of the Jewel, among them, Maurice Bishop. In March 1979, during Gairy’s absence from Grenada, the New Jewel Movement seized power with the full support of the Grenadian people who left work, school and homes to throng the streets. Three persons died.

“Forward ever” was the battle cry of the revolution.

Beverly Steele, historian, commented, “Had Maurice Bishop called elections then, he would have been legitimately in power for five years.”

For many, it was good riddance: “Gairy had become an embarrassment to Grenada.” More than 60% of homes had no pipeborne water, no electricity; there was 30% unemployment, 70% among women. The people’s revolution brought education, empowerment, built homes and boosted an economy that had been stagnating for decades. By the end of the first year, the unemployment rate had dropped to 14% and the gross domestic product had doubled; in the second year, it doubled again; and in the third year, doubled again. How was that possible?\

“In a revolution,” said Bishop, “things operate differently.” Bishop’s “big revolution in a small country” was endorsed by Michael Manley of Jamaica, Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, and Fidel Castro of Cuba.

It was the Soviet-backed Cuban support that most frightened the USA. Grenada “is not a friendly island for tourism,” declared President Ronald Reagan, “it was a Soviet Cuban colony being readied as a major military bastion to export terror and undermine democracy.”

There were always Americans in Grenada.

“They tell us a lot of things that aren’t true in the US,” declared one enthusiastic visitor.

Progress was not without its price. Press freedom during the early 1980s was curtailed. The People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG) had passed a law that a newspaper company could only be established with 27 persons as directors. Newspaperman Leslie Pierre said, “Too many people (unwilling to accept the propaganda) were imprisoned between July 1981 and 1983.” Some estimate there were 1000 imprisoned without reasons; others say the figure was probably 3000.\

“All revolutions involve dislocations,” said Bishop. “The revolution must survive.”

The tone throughout the film is unsentimental; edited with a keen ear for the exact detail to move the story forward. Musical punctuations are timely and effective. The story gains momentum and is propelled by simple language spoken by real persons, the facts plainly told.

Paddington retrieved archived footage from the Library of Congress (USA); from Cuba’s state organization and independent filmmakers. The team included Oliver Milne, Princess Donelan and editor Luke Paddington.

Forty minutes into the film, we see the experiment unraveling. It’s a painful denouement; the events of one day, October 19, told and retold with different levels of disbelief. Maurice Bishop, freed from house arrest, is carried by the celebratory crowd to Fort Rupert. The People’s Revolutionary Army brought out their armoured cars and took control. We know the end.

The second half of the film belongs to the People’s Revolutionary Army. Callistus ‘Abdullah’ Bernard, a lieutenant in the People’s Army, is the anti-hero. A clear line had been drawn. “Civil war was imminent.” Among Bishop’s last words, “They have turned the guns on the people, oh my God.”

In the upper room of Fort Rupert (renamed for Bishop’s father), “Jackie Creft was terrified. … I am so scared, something terrible is going to happen.” Ann Peters remembers thinking, “We are all going to die.” \

Before the end of that day, Maurice Bishop and members of his government – Jacqueline Creft, Fitzroy Bain, Norris Bain, Evelyn Bullen, Evelyn Maitland, Unison Whiteman and Keith Hayling – were placed against a wall at Fort Rupert and executed. There were five shooters, Callistus Bernard, Lester Redhead and three privates. “We opened fire on them,” said Bernard, and “I take responsibility for what happened.”

On October 25, days later, 1900 US marines landed on Grenada, ostensibly to safeguard American students and others still there. “Grenada was without a government,” said President Reagan, and there were more than 1000 US citizens at risk. Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of England, denounced the US invasion. The governments of Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Belize distanced themselves from the invasion. In Grenada, many – business owners as well as members of the then and subsequent government – feel that the invasion was justified, the only way to restore order after the killing of the Prime Minister.

The bodies of Bishop and those who died with him were never found. Bernard Coard who spent several years in jail and was recently released, claims “The Americans have the bodies.”

Who was behind the murder of Maurice Bishop and the leaders of the Grenada Revolution apart from those who pulled the triggers? “Can a private in any army put a prime minister against a wall and shoot him?” The anguish is palpable. Murderers are alive among us. The murdered are ghosts whose brief lives shine the way forward. Forward ever.

There are more questions than a single account of contemporary history can answer. Forward Ever is an excellent start, a model for filmmakers who may wish to investigate their history, to find themselves. Two years in the making, it was shown in Grenada on the 30th anniversary of the death of the revolution (October 19, 2013). Since then, wherever it has been shown, each screening was followed by lively discussion. DVD copies of the film are also available. |