|

September 2014

Issue Home >>

|

The place is a small island nation, Trinidad. The time is just over a year: thirteen months between Labour Day in 2009 and July 2010. The personae dramatis belong to a small family: Charles Butcher, his wife Marie Elena also known as Elena or Lena or Mrs B, their daughter Ruthie; specific friends and extended family. The Butchers and their set are middle class, upwardly mobile, creole Trinidadians. The place is a small island nation, Trinidad. The time is just over a year: thirteen months between Labour Day in 2009 and July 2010. The personae dramatis belong to a small family: Charles Butcher, his wife Marie Elena also known as Elena or Lena or Mrs B, their daughter Ruthie; specific friends and extended family. The Butchers and their set are middle class, upwardly mobile, creole Trinidadians.

Trinidad of Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw’s first novel (her previous work, “Four Taxis Facing North” is a collection of short fiction) resembles the island we are all familiar with, those of us who live here. Murder rate and road deaths are standard on the daily news. Crime, violence and corruption in politics are commonplace markers in the humanscape. Almost as pervasive is the sybaritic tropical landscape: the beach, “down the islands,” the hotel swimming pool, the Savannah. An existence that is hedonistic on one hand, hemmed in by the fear of violent crime on the other, is real life for the Butchers and their set. In their creole culture, routines include Maracas on Sunday; playing mas around their own cart is an annual ritual.

We see in Elena – Mrs B – the child left by her mother in the care of a kind but reserved spinster aunt. She never developed the means or desire to express an emotional side, and seems unwilling or disinclined to bridge the divide that might bring her closer to her husband or daughter. The story may be the mother’s, but Walcott-Hackshaw allows us a look at her absentee mother. She also exposes the hearts of daughters who would be different from their mothers, but are not.

The year brings change that is not quite predictable, and cracks of introspection appear in Mrs B’s otherwise seamless life. She stands aside to regard the daughter who is already a big woman, unfathomable. The sense of loss is persistent: the lover, the child, the passing years.

Perhaps “Mrs B” was inspired by Gustave Flaubert’s first novel, “Madame Bovary” (1856-57). The realist style, the precise and spare phrasing, even the architecture – three parts, each with discrete chapters – frame a worldview that might owe its definition to nineteenth century literature. Be that as it may, a classical foundation is an excellent place to start. Think “Pride and Prejudice” which preceded “Madame Bovary.” But this is not a story stuck in a bygone age. Here is a 21st century world where women like Mrs B are fortunate and perhaps fewer than we know: the independent kept woman; free to travel alone; given “space.” We may or may not like her, but we know someone just like her.

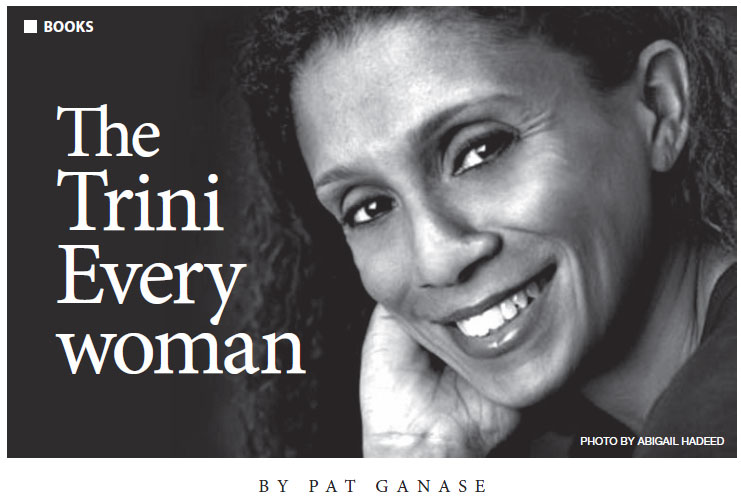

It is by no means a feminist novel, though it is a woman’s view. What “Mrs B” is, is a year in the life of a Trinidadian “everywoman” who has fulfilled society’s expectations of wife and mother. Almost 50, self-reflection comes slowly, an unremarked process. Subterranean change may be taking place, but do we know?

Flaubert’s adventures of “Madame Bovary” were written – and serialized – to titillate in an age with fewer freedoms, fewer entertainments. Walcott-Hackshaw’s “Mrs B” achieves its momentum at a casual walking pace, perhaps deceptively so. It imposes a cinematic distance – we see the action – with minimal dialogue and evocative settings. The human activities have a backdrop of scenic lushness and variety – of Trinidad, its forested hills and shores. This is the kind of book that might easily become a film or, serialized, a Trini soap opera.

This is also the kind of book that the education council may put on the syllabus of high school students. You can imagine the questions on examination papers. Like mother like daughter: discuss how this applies to Mrs B and Ruthie. How does the environment of Trinidad as described in “Mrs B” influence the actions of the characters. Is Charles Butcher the typical Trinidadian man?

Elizabeth may be Derek Walcott’s daughter. Whatever challenges or examples she may have imbibed from her famous father, this is her own voice, her unique perspective. “Mrs B” is an elegant first novel with the delicate sensibilities of a Trinidadian woman. |