“There are two writers I have always felt that make me very mad - Joseph Conrad and VS Naipaul,” said Professor Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, almost at the very beginning of his lecture.

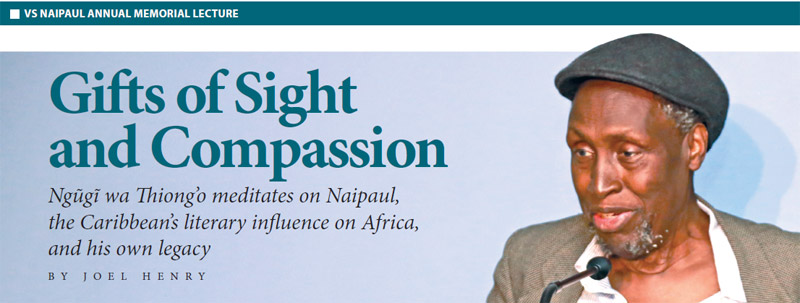

Ngũgĩ, one of the greatest living writers today, was at UWI St Augustine’s Institute of Critical Thinking, speaking at the Launch of the “Lines of Life” Project and Annual Memorial Lecture for the late Sir Vidya S Naipaul. Yet he did not shy away from a critical assessment of Naipaul, a fellow giant of literature and contemporary of the colonial and post-colonial era.

The author of A Grain of Wheat, one of the 20th Century’s foundational anti-imperial novels, said both Naipaul and Conrad had gratitude to “the empire” and grudges against the empire.

“But why do we come back to their work again and again?” he asked rhetorically. “Both writers had the gift of sight. And no matter how uncomfortable he may make you, Naipaul forces you to look again and again.”

It’s that capacity for nuance, that ability to work through uncomfortable ideas and information, and a moral core that defaults toward compassion and understanding that have made Ngũgĩ one of the most beloved figures in literature.

The Kenyan author, now 81, was certainly beloved by the audience at the Institute of Critical Thinking on August 17, which included UWI staff and students, lovers of literature (Ngũgĩ’s, Naipaul’s and writing in general), aspiring writers, and even members of the Naipaul family. Among them was former UWI St Augustine Campus Principal and Member of Parliament for Caroni Central Dr Bhoendradatt Tewarie. Dr Tewarie established the institute during his tenure as principal.

Professor Kenneth Ramchand, renowned scholar and master of Caribbean literary criticism, was also present, to the delight of Professor Ngũgĩ. In his address he mentioned Ramchand directly:

“I looked desperately,” Ngũgĩ said, after discovering West Indian writers in the 1960s, “for any other scholars who were digging into this wonderful literature and the only one I could find at the time, was Kenneth Ramchand.”

The launch and lecture were hosted by the Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies (LCCS) within the Faculty of Humanities and Education. The chair of the event was Dr J Vijay Maharaj, lecturer in LCCS as well as coordinator of the Lines of Life project. Lines of Life is a digital platform containing a trove of information on Naipaul and his work.

“I would never have dreamt that it would be VS Naipaul who would be the occasion of my first foot in Trinidad,” Ngũgĩ said after thanking Dr Maharaj for the invitation to the country.

He told the audience of his relationship with Naipaul, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Caribbean. Ngũgĩ’ has a surprising depth of knowledge of Caribbean literature and history. He spoke about the “large debate about the place of Africa in the Caribbean collective self-consciousness”. Trinidad, he said, “has been at the centre of the quest for answers.

Ngũgĩ’ spoke of Trinidadians such as Henry Sylvester Williams (organiser of the first Pan African congress in 1900), George Padmore (organiser of the 1945 Pan African Congress in Manchester), Kwame Ture/Stokely Carmichael (leading black socialist during the American Civil Rights Movement) and Claudia Jones (social activist and founder of the West Indian Gazette, England’s first major black newspaper).

He spoke of his meetings with CLR James, another of Trinidad’s greatest writers and thinkers, and their shared appreciation of Caribbean authors such as Naipaul.

“Our mutual interest in Naipaul drew us closer together,” Ngũgĩ said.

Most surprisingly, the Kenyan writer spoke of the impact that Caribbean writers such as James and Barbadian George Lamming had on Africans. Ngũgĩ recounted how Jomo Kenyatta, Kenyan anti-colonial activist and leader, while on trial was asked by the imperial prosecution how he, an African, came to know about slavery.

“He cited James’s The Black Jacobins as his authority,” Ngũgĩ said. “I narrate that to show the global reach and effect of the Caribbean writers of the Lamming and Naipaul generation.”

Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin, was particularly influential on Ngũgĩ himself, he said, “I felt Lamming’s narrative power speak to me and my Kenya situation so directly, that, as I have acknowledged in my memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver, it influenced the theme and the writing of my second novel, Weep Not Child.”

He said his contact with the Barbadian writer would eventually lead him to “struggle to move the centre” (a concept of breaking the stranglehold of Western culture as well as oppressive norms within indigenous cultures).

“I would pay the price of prison and exile for that very struggle. But it is a price I am proud to have paid,” Ngũgĩ said, describing his time of imprisonment by the Kenyan government for the uncensored and highly progressive works produced by the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre. After his release in 1978 he was forced into exile for over two decades.

Ngũgĩ’s description of this time in his life was particularly powerful. “I found myself a prisoner with only a number for a name” he said. For three weeks he was held in “internal segregation”. The other prisoners were not allowed to talk to him. Isolated, he imagined himself a bird, first flying out to visit family, then, as his fantasy developed, flying to play tricks on the guards.

“Then one day, it dawned on me,” he told the engrossed audience at the Institute of Critical Thinking, “this going out and coming back at will, was what I did night and day. I visited my family. I walked the streets. Suddenly I realised I had the wings of a bird: Imagination was my wings of glory.” “Then one day, it dawned on me,” he told the engrossed audience at the Institute of Critical Thinking, “this going out and coming back at will, was what I did night and day. I visited my family. I walked the streets. Suddenly I realised I had the wings of a bird: Imagination was my wings of glory.”

This revelation he said, gave him the power to write the novel Devil on the Cross, on prison toilet paper.

“The capacity of the arts and artists to make us look again, feel again, touch again, listen again, even challenge us to make us realise that the human is a continuous invention, that to me, is still the greatest function of the writer and also the challenge,” Ngũgĩ said in the remaining moments of his address.

Like Naipaul, like Lamming, like all those that have emerged out of the colonised East and West, he has provided that function with a powerful eye and pen, but with his unique gift of empathy.

|