Within three months of its discovery, COVID-19 became a global pandemic. At the time of this writing, the virus has a whopping death toll of over 828,000 lives lost. There are certain truths about this virus that cannot be denied. People with chronic conditions are at greater risk of having poor outcomes (ventilator use or death). These include: high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, cancer, heart disease and lung disease. In Trinidad and Tobago, this trend was also observed, where pre-existing medical conditions were mentioned among the 17 (at the time of this writing) reported deaths. Even without the pandemic, diabetes, heart disease and cancer are among the leading causes of deaths in the country.

These medical conditions are closely linked to maintaining a “poor” diet, that is, one consisting of predominantly carbohydrate-rich foods such French fries and conveniently prepared foods like roti, doubles and bake. Even more alarming are the toxic ingredients found in these foods, one of which is known as acrylamide.

Acrylamide is a cancer-causing substance which is formed when carbohydrate-rich foods are prepared at high temperatures (greater than 100 oC). These foods contain sugars such as glucose or fructose that interact with an amino acid known as asparagine at high temperatures, resulting in acrylamide formation. This process is known as the Maillard reaction, which is responsible for producing the brown colour, flavours, and aromas that make our food so appealing. However, the browner our food, the more intense the Maillard reaction. This means the greater the levels of acrylamide present. Fried, baked, or roasted foods that are browner and crispier, contain higher acrylamide levels than boiled foods.

The acrylamide content for many fast and conveniently prepared foods popularly eaten in the Caribbean have been assessed by food scientist Dr Grace-Anne Bent. Examples of these foods include fried potatoes, fried bake, roti skin, bread, cereal and coffee. They all contain moderate to high levels of acrylamide. This is in contrast to boiled foods which contain no or low acrylamide levels.

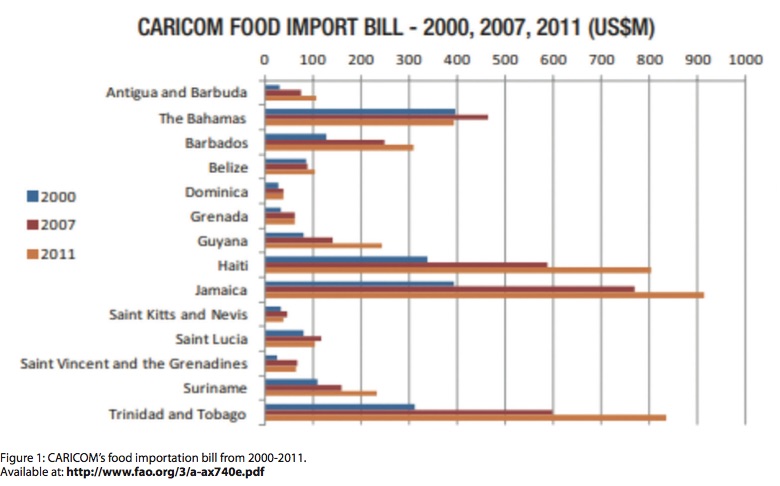

Data obtained from food imports and food service sales support the country’s growing preference for refined carbohydrates instead of fresh fruits and vegetables (Figure 1).

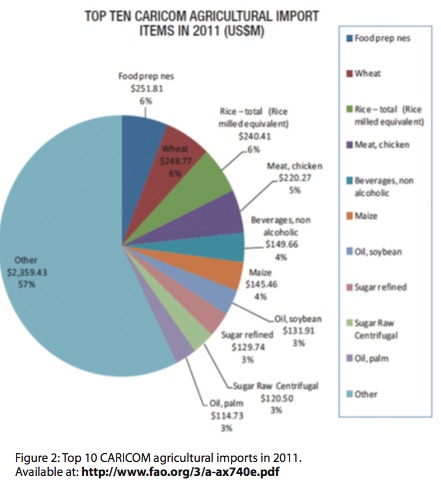

This provides clues to the population’s increasing acrylamide exposure. Some of the top foods imported into the country are coffee, wheat products, soybean oil and refined sugar (Figure 2). This is not surprising since many food items are made from some of these imported products. These foods contribute significantly to high levels of acrylamide in our diet. While 70 per cent of these imported foods move to retail outlets, 30 per cent can be found in food service sectors, including the international fast food franchise KFC, which has been rumoured to generate the most sales on the island. The number of fast food service outlets are increasing exponentially due to the growing labour force among the population, particularly women. Meanwhile, agricultural productivity remains low, contributing less than one per cent of the country’s GDP.

So, what is the relationship between fast foods and COVID-19 deaths? When we eat fast foods they significantly increase our exposure to acrylamide. Once eaten, acrylamide lowers the body’s internal levels of the key antioxidant glutathione (GSH). GSH serves as the body’s natural detoxifier. GSH levels are quickly reduced when removing harmful substances such as acrylamide from the body. Once GSH levels are low, toxins begin to accumulate. This leads to a faster ageing process and chronic diseases that may result in poor outcomes for a COVID-19 patient.

Exposure to acrylamide can also compromise the immune system and with it the ability to combat COVID-19. Acrylamide lowers the number of immune defense cells that work to produce antibodies, kill viruses, control cell movement and develop antiviral functions. Without these defense cells, the body loses its ability to combat infections. Since there may be a link between lifestyle diseases, acrylamide consumption, and poor COVID-19 outcomes, we encourage an improvement in eating habits. Our diet should include foods rich in proteins, fruits and vegetables. Currently, agricultural land in Trinidad and Tobago is being overtaken by urbanisation. We should strive to increase local production of fruits, vegetables and ground provision. This may be possible with government assistance and public education campaigns.

Additionally, cooking methods that require lower temperatures such as boiling, and eating fresh fruits and vegetables should be promoted. Not only will this aid in reducing our food importation bills, but will encourage healthier eating and make food more affordable. By reducing the consumption of processed, starchy foods, the exposure to dietary acrylamide will be reduced, thus enhancing immunity and the overall health and well-being of the population.