EDITOR’S NOTE: On September 22, Campus Principal Professor Rose-Marie Antoine gave the feature address at The Rotary Club’s “Hats and Heels High Tea and Fashion Show” at the Hyatt Regency Trinidad. UWI TODAY is pleased to share an excerpt from her address.

When I heard today’s fascinating topic, I thought, “Finally someone gets it.” Education is indeed the foundation for peace and social justice. Ultimately, education is a social and collective right. It promotes a social and collective good – social cohesion – peace, justice.

Not many believe that these days, steeped as we are in apathy and self-indulgence. We tend to focus myopically on the short term and individualistic goals of education – getting a job, etc., but its true goals are much broader.

But then Rotary has always been a progressive organisation. It understands these intersections and sometimes invisible limitations in our societies. For example, your work on period poverty, recognising the link between female bodily functions and equal opportunity/advancement (being able to go to school). I was honoured when, 3 years ago, Rotary approached me to assist with that programme.

Just as education empowers, and promotes social justice, so too, social justice and peace promote genuine education and opportunity. So, this is a complex and hugely important subject. And of course, if you chose such a serious topic, one assumes that you want a serious discussion.

We cannot interrogate this topic without considering the issue of inequity which I have always believed is the root of all evil. I have spent much of my work-life advocating for equity and justice. Inequality is also a constant challenge that we must continually confront, even more so that our societies were born out of brutal inequality. To state the obvious, without social justice, there can be no peace in our societies.

That is the important truth that we must grasp. Look at Denmark – happiest place in the world. It is because they have actively addressed inequity.

Inequality breeds injustice and injustice catalyses conflict, the opposite of peace. We as human beings cannot thrive or survive if others in our societies are disenfranchised or marginalised.

There is no blame game here. We must create the social structures that prioritise these goals of social equity, and education remains the fundamental tool to do this.

Interestingly, we are not even achieving those short term goals of education. Fewer are now able to use education to climb out of poverty. A large percentage are failing – achieving below 50%. The odds against success are greater than ever.

A young man smiles during his graduation ceremony. Over time, higher education has become less attractive to youth, especially males

It is no secret that we are witnessing the decline of education as a priority in our communities, our governments and even industrial sectors. Some of that is due to what I call the Bill Gates phenomenon. Both himself and Zuckerberg (Facebook) dropped out of university, although they did make it to Harvard. These are rare successes. We must fight against this growing cynicism that education is not valuable, whether it is the ordinary person on the street or the policy makers.

The results – a lack of funding and the undervaluing of education, tertiary in particular – continue to be major challenges. But it is a more pervasive problem. Education has become less attractive, especially to our male youth, and possibly some ethnic groups, whether as a path to gaining livelihoods, or as an end in itself.

Of course, some of that disillusionment toward education comes from embedded social practices which encourage nepotism instead of merit, achievement and hard work.

It is therefore not enough to simply provide education, as we are fond of boasting (although, we are not even doing that well). We now have the task of persuading young people, especially males, that an education is something worth having. We cannot do that by carrying on as usual.

Recent research highlights clear gender dimensions in the pushback against education. Education is no longer a male domain, and we know today that girls are outperforming boys in every academic field and are the majorities in universities. It is good that women, long denied opportunities, are progressing, but there is a dark side. While male marginalisation is debunked, David Plummer and others argue that “with education becoming ‘common ground’, boys are left with fewer opportunities to establish their gendered identity through education”. So, since academic achievement and the classroom are no longer meeting those needs as easily, have less value for boys in establishing their masculine identity, education is less attractive to them. In fact, boys who excel in academia risk being considered “suspect”, nerdy or even gay by their peers. So, masculine taboos have entered the classroom. Education is seen as feminised and not something a ‘real man’ would do.

These same gender dimensions help explain the meteoric rise in gang violence and murder. What emerges are links between this gendered identity dilemma and social conflict. The “desire to prove male identity is being driven towards risk-taking, hyper-masculine, sometimes antisocial acts including bullying, harassment, crime, and violence.”

That machismo – the search for an empowering identity, to project oneself as successful and masculine – helps to explain the staggering level of violence in our society. Unless we can address these, peace will continue to be illusory.

The research also shows that for boys, the peer group is most powerful, more than family, school, and media, and assumes a culture and authority of its own, particularly where there is a power vacuum, like a lack of supervision. The peer group is the genesis of the gang culture and self-perpetuates. Importantly, these peer-group values start with us, including our mothers, who instill these rigid hyper–male/hard masculine norms.

“The combination of masculine obligation and taboo narrows boys’ potential and cuts them off from large areas of social life”, including education. Males are depriving themselves of the social benefits of education that can lead to their empowerment. It is a paradox; they are marginalising themselves.

Statistics from the prisons confirm this. Reports say that 50.3% of inmates did not complete school. Incidentally, I noticed this phenomenon several years ago while doing a UNICEF project. Many of the ‘juvenile delinquents’ had dropped out of school and had learning difficulties, such as dyslexia. Yet, nothing has been done to design education programmes to harness these children. They are left to self-destruct. Note that Einstein had dyslexia.

We are now beginning to understand the phenomenon and can devise solutions. We must, therefore, create routes for males’ advancement. No one demographic should be over-represented if we want a peaceful and egalitarian society. One route will be redefining our notions of masculinity – a longer term goal; another is making our classrooms more attractive to accommodate male notions of identity. For example, recently I attended an exciting joint Browne University/UWI Future of Science Symposium. A fascinating input was work on the relationship between science and music. It seems that music is mathematics in a pure form. All of its harmonics can be expressed in maths, described by physics, and coded by computer science. Who knew? I was immediately drawn to the possibilities in our culture, which still finds music attractive for males. This is one way of reconnecting masculinity with educational achievement.

In our local context, we think of peace not so much like the Gaza war scenario but the huge crime and violence rates. Today’s youth is more likely to be carrying a gun or knife in his bookbag rather than the future.

Gang culture and violence are therefore only partially explained by factors such as Trinidad and Tobago being a transit point, or increased guns. Baird and Kerrigan argue that “gang culture is a historically rooted,... male hegemonic street project.” Note that Latin America and the Caribbean are noted for their machismo – and have the highest murder rates in the world.

Importantly, this missing element of male hegemony is born out of a fragility which itself “stems from historic patterns of exclusion and poverty, the legacy of colonialism and slavery and the failures of contemporary development”.

So, at the root once again lies inequality, marginalisation, unequal power constructs – whether gender or class – the true culprits for the absence of peace.

Isn’t this pointing to proactive, early interventions for those, especially males, in under-served communities?

I believe, too, that we should reconsider our newish segregated community model – creating more and more ghettoised-like housing blocks, juxtaposed with well-to-do gated communities. This exacerbates marginalization and conflict. I know that this is not easy to reverse. It is a vicious cycle. We live in gated communities because we are afraid, but their very existence undermines community, respect and tolerance and increases the risk for that fear. Australia, for example, has moved away from that model.

So, crime is not the government’s fault, but it is the government’s responsibility because the kind of radical social revolution that needs to take place requires government support and leadership.

In many ways, education has become less accessible and less equitable. I was criticised for stating that we have an unequal education system. Post-COVID and thanks to CNC’s excellent programming about the many disadvantaged persons in our country, some who are unable to go to school because of poverty, that disbelief might be waning. A child going to school on a hungry belly twice a week, or who must help their parents on the farm at 4 am, does not have an equal opportunity to one with degreed parents, proper nutrition, a laptop, and being driven in a Benz.

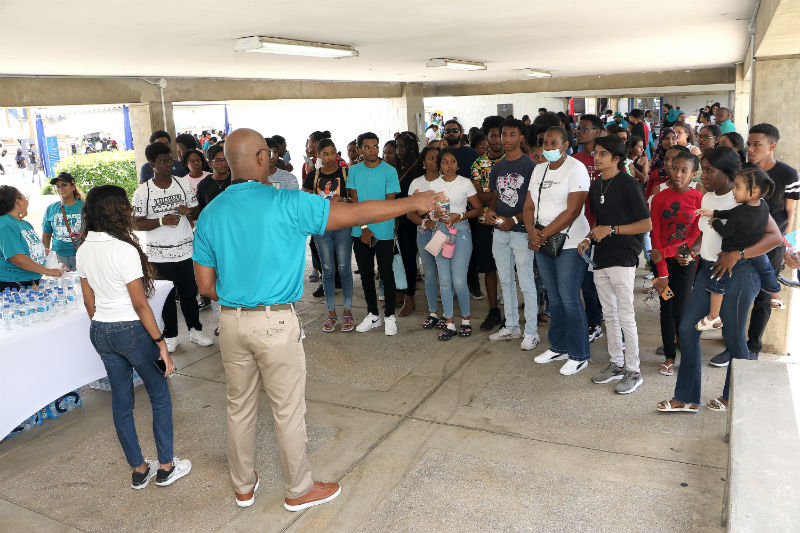

Prospective students listen intently to a campus guide during one of UWI St Augustine’s Open Days. Events such as Open Days give people curious about the opportunities in higher ed to visit universities, tour the campus, speak with lecturers in their fields of study, and find out about financial aid.

Our education system does not create genuine equal opportunity, and our social welfare systems must find ways to level the playing field in education. I also advocate for broader criteria for access to tertiary education. We already accept that our talented sports people are given scholarships to top universities in the US using differential academic criteria.

If we are serious about the stability of our society and true development, our educational framework must move toward a more progressive, empowering, inclusive approach to access, expanding to the under-served and forgotten, more sensitive to the socio-economic and cultural constraints to accessing education. Admissions can no longer be based purely on CAPE results because getting results is not an equitable process. If we do not, we give up on those, especially young men and those from rural and disenfranchised communities, with so much untapped potential, if given a fair chance, a second chance. This does not promote empowerment, or peace.

If we want positive change, we must think and act differently. My heart broke just this week when I learned that a young man whom I had facilitated an application to the MYDNS/UWI Agriculture programme had not gained entry. This is a man on remand for over 10 years, recently released. The reason given was that he was above the age limit.

To those who still want an education, it has become more expensive. Consider, for example, the huge amounts to be spent on books, uniforms, transport, and accommodation. Why can’t we return to a schoolbook programme? It is increasingly inaccessible. I was shocked during COVID when I discovered that 65% of my students in the Law Faculty had either no computer or no Internet access!

Just this week, my gardener informed me that his daughter was crying and refusing to go to school. They had no money for books and uniforms, and she was afraid of being bullied. These are real dilemmas to many families.

Governments are also investing less percentage wise on education, or cutting corners. Schools in need of repair, declining services, low salaries to teachers and university lecturers breed high rates of attrition and falling quality assurance. Recent cuts to tertiary institutions, including The UWI, where there are longstanding receivables from GoRTT for millions of dollars in fees owed, tell its own story. We are now at a crossroad, and as a nation, must re-assess and re-commit to education as an asset – kindergarten to tertiary. There needs to be a national conversation on the economic and social benefits of genuine investments in education.

Ironically, we continue to use our scarce foreign exchange to prop up other foreign countries and universities, many of those universities ranked much lower than our own UWI in the global rankings, because we remain wedded to a colonial mentality, ignoring the negative impact this phenomenon has on our societies, including the brain drain and graduates devoid of the desired social connections and consciousness.

It is well documented that the positive genuine investment in social welfare that emerged in the 1950s after the world wars, recession and Spanish flu – pension, subsidised housing, free education, healthcare and more – have now been replaced by the Washington Consensus of the 1990s, leaving huge social protection deficits and increasing poverty. GDP booms did not trickle down; the rich simply got richer.

We also embraced free market programmes which destroyed local industry, and reduced employment and standards of living, leading to a nation of retailers. Governments stopped subsidising their national institutions or industries, including education, manufacturing and agriculture. Note that the First World continued to subsidise its agriculture.

It’s not just the government, but the private sector. The glorification of the retail sector means that there is little or no interest in building an innovation sector, or producing anything. This means also little interest in research. The third world countries that succeeded, such as Singapore, embraced research and development, which are key aspects of education. Barbados seems to be trying. Its private sector is funding a groundbreaking sargassum project to fuel vehicles. Believe it or not, it is being spearheaded by a Trini inventor who started here at St Augustine, but could get no private industry or government to fund her in Trinidad. At UWI, we have great difficulty getting funding for our scientific inventions.

These are recipes for disempowerment, conflict and perpetual inequity, not peace and justice. The latest data from the UN confirm that the main causes of high levels of criminal violence is income and social inequality.

It is therefore not accidental that the murder rate rose from 84 in 1990 to 610 in 2022.

Far-reaching, structured preventative social interventions – community and social psychological programmes, accessible quality education - are needed. Handouts, like food cards, short-term work and going to the media to seek help, are necessary but not sufficient. Reddock, who has long advocated for these, advises that “Investments in the social sector today will reduce costs in virtually every sector in the future [leading to] an overall improvement in the economy and the quality of life for all citizens.”

There should be a broader vision of education, not just on the narrow constructs of books and schools. Education is also about using information, not fake news, to socialise and inculcate desired positive values, building tolerance, embracing and adapting to change and science in the dynamic environment that we inhabit - from vaccines and climate change to AI.

It was research that revealed the medical potential of cannabis/marijuana, dismantling the ignorance and fear about this plant and the inherently unjust legal system/laws which criminalised and incarcerated thousands, especially the young and marginalised. I was honoured to lead this programme as Chair of the CARICOM Commission on Marijuana, and saw the impact first-hand.

First year students attending Matriculation 2024. Despite the social and economic factors pulling people away from education at the tertiary level, thousands still do make the investment in their future.

Education is also the path toward dispelling stigma and discrimination that fuel hate and conflict, as we saw with LGBTI, HIV and, of course, gender based violence, which is atrociously high. Note my earlier points about machismo that locate ‘real men’ at the top by subordinating women, relevant here. We know that the subjugation of women is on the rise whether in Afghanistan, India, the Caribbean, or Trump and Vance’s America.

This week’s alarming statistics on teenage pregnancy – 176 cases last year - is another example. The FPATT, which I have the privilege to lead has for many years, called for comprehensive sex education in our schools as a preventative tool.

Blissful ignorance has never been a pathway to progress or peace.

I end where I began. Equity is a core life value. Education is its tool leading to genuine social progress and peace. The true meaning of rights like equality resides in economic and social rights, such as health, work, environment and, most importantly, education.

Education is a community good and a community’s responsibility. It must address intricate social problems if it is to succeed. Are we willing to create that change, to be disrupters of the status quo where it does not truly work for its purpose, or for the majority of our citizens? I wonder, if we were convinced that not taking that extra fat bonus, or paying those extra taxes (those of us who do pay taxes), would result in less crime, so that we could once again go to bed with the doors unlocked and take a stroll in the neighbourhood, would we do it?

So, part of that education mantra has to be about educating ALL of society of the value of education, the value of social justice and peace.As I said, big topic. The system today is simply not working. It is too individualistic, focusing on short term outputs, failing even that goal. It must embrace social justice and empower the marginalised if it is to create socially just, peaceful societies, and must itself be equitable and accessible. This requires an overarching philosophy, early interventions and long-term investment.

I hope that this tidbit will generate further research-funded research – and discussion, so that, together, we can forge a better way forward.