SUNDAY 23 APRIL, 2017 – UWI TODAY

13

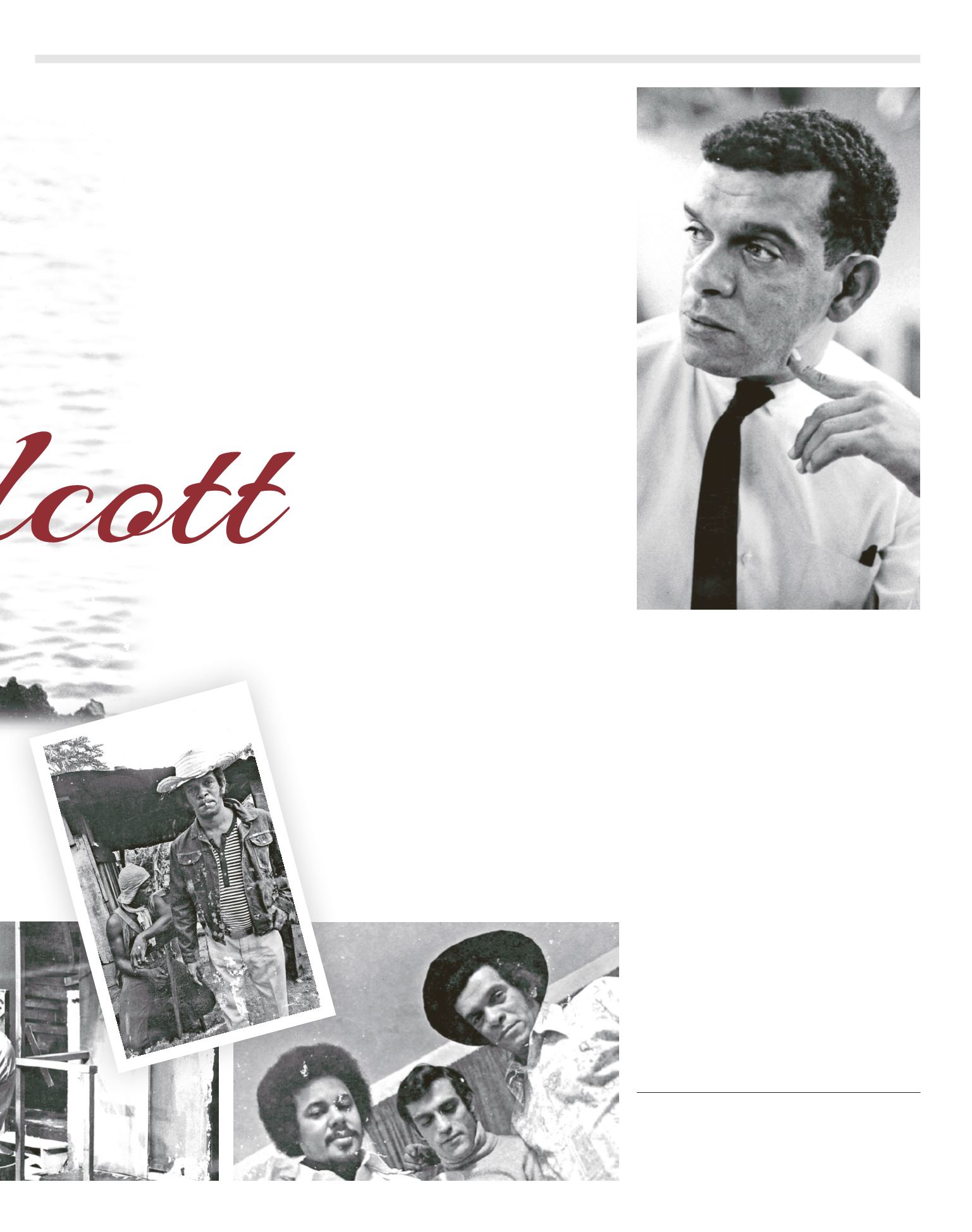

Dr Jean Antoine-Dunne is a Walcott specialist and

recently retired as a Senior Lecturer in Literatures in

English and Film at the St Augustine campus.

Her book Derek Walcott’s Love Affair with Film,

published by Peepal Tree Press, is due out in October.

E A N A N T O I N E - D U N N E

Tribute to

and repression. These all appear as the sources of artistic

potential and production.

“O Starry Starry Night” pays homage to St Lucian

artist, Dunstan St Omer, who died two years ago and

as with so many of Derek’s other works, foregrounds

the interactive relationship between the arts and his

multifaceted talents. Derek was a fine painter and

continued painting until almost the end.

His final work in 2016, “Morning, Paramin” was

a collaboration between himself and the painter Peter

Doig. In a sense it continues in the tradition of “Tiepolo’s

Hound” (2000) in which as a painter he meditates on the

nature of light and perception. The inclusion of his own

paintings in “Tiepolo”

engages readers in the debate about

the relationship between word and image, but also on the

marginalisation of the black in the context of European art.

He wrote essays, many of which have become central

to the debate about what constitutes Caribbean art and

Caribbean identity. His Nobel speech “The Antilles” has

already provided critics and politicians with a language of

definition in its imaging of a broken vase:

“Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the

fragments is stronger than that love which took its

symmetry for granted when it was whole. The glue that fits

the pieces is the sealing of its original shape. It is such a love

that reassembles our African and Asiatic fragments, the

cracked heirlooms whose restoration shows its white scars.”

It is significant that for the poet this is “the exact

process of the making of poetry, or what should be called

not its “’making’ but its remaking”. For Derek Walcott was

a supreme craftsman. In “Arkansas Testament” he reflects

on the artisan-like process of making poetry. But this

craftsmanship was of necessity a quest for an echo of the

landscape and the asymmetrical nature of life and art in

the Antilles. His perpetual search for such a form led to an

apprenticeship to many masters, and evolved over the 70

years of his career. It led to a search for new metaphors that

would come from the land and history. So for him the word

pommerac represented an historic language bequeathed

by the colonisers and also signified a vestigial trace of the

Aruac presence and the many layers of trauma that have

made the Caribbean the rich repository of culture that it is.

This idea is equally present in his plays. At the

rehearsals for

Steel

, he sought to ensure that the very

movement of the Caribbean body and the music of the

place would shape the production. He brought into one

theatrical space the raga and the dance movements of

masqueraders and of Shouter Baptists as part of his ongoing

attempt to show Caribbean art as syncretic process and as a

meeting of different cultures.

Many of his plays did not receive the same recognition

as his poetry, though it might be argued that the stage

was his great love. But no one could deny the beauty and

the success of “The Joker of Seville,” in particular at its

Boston performance. “The Joker”

exemplified that unique

combination of witty social commentary, sexual innuendo,

characterisation and beautiful poetic language all united by

music and movement. It is equalled only by “Ti Jean” which

has seen many incarnations, finally emerging as “Moon-

Child” in 2011.

Walcott also wrote film scripts. Many of these are

stored in The UWI and University of Toronto archives,

but only two have been produced: “The Rig”

and “Haytian

Earth.” His work anticipated the now current conversations

about the relationship between film, digital and literature.

The long poem, “Omeros,” is filmic in its structure and

in this way allows the poet to create a conversation between

the major writers of the Caribbean, including Kamau

Brathwaite, VS Naipaul and Wilson Harris, whose concept

of simultaneity he sought to express through montage.

In this work he returns to the debates of the ’60s and ’70s

about the importance of Africa. He also pays homage to

those influences that he had long acknowledged, from

Homer to Yeats and Joyce to Lowell and Chamoiseau. Its

multifaceted and polyphonic structure makes it an epic

beyond compare.

Derek Walcott’s loss leaves a huge gap that cannot be

filled. But his legacy as a man and as an artist remains.

For Professor Emeritus Gordon Rohlehr,

“Walcott was a mega mind, an enormous intellect,

which was constantly searching out the pathways we should

traverse. He never dabbled but delved deeply into literary

imaginaries, into mythic and the folk sensibilities, into the

visual as painter and filmmaker, into song as the producer

of musicals. Consider for example that our understanding

of what he produced would be incomplete until we take

into account the over 500 pieces which he wrote on diverse

topics in the “Trinidad Guardian” in the six to seven years

he spent as a journalist there.”

Walcott’s life and work transcend simple assessments.

It is this sense of a complex intervention into the nature

of Caribbean art and the sensibilities of the region and his

project of giving voice to this multiplicity that may well be

viewed as his most enduring gift to the Caribbean.

PHOTOS COURTESY THE DEREK WALCOTT COLLECTION,

THE ALMA JORDAN LIBRARY