SUNDAY 6 AUGUST, 2017 – UWI TODAY

9

“At the time we put forward the view that the university

would look to abolish the term ‘non-campus territories’ and

we advocated that it should be called a fourth campus. It

became the Open Campus,” he said.

He feels that was a good move.

“The main thing out of that of which I am particularly

pleased is the idea of a more visible presence in every one

of the contributing territories, and the idea of them coming

together under one. I am pleased to be part of the genesis

of that idea,” he said.

While the University’s brand as a regional institution

remains strong, the increased autonomy of each campus and

the reduction in themovement of students among campuses

have diminished the “West Indianizing” experience that

shaped earlier alumni. Despite its claim, does he think the

University actually functions as one entity?

“I have agonized about this. You have to think about

what you lose and what you gain. There is no doubt thatThe

UWI could not retain its function as a small, elitist campus

inMona. It could not retain its function. [Sir] Arthur Lewis

was very clear on that; the massification of education had

to be the route to go. And once you take that route, it is

inevitable you lose that closeness that comes from a small

campus where everyone lives together.”

Even though the intimacy has practically gone, he

has still found evidence of regional spirit, citing a paper

presented by students to the Council a few years ago

asking that the WI be put back into UWI. “That was what

the students themselves were articulating for: more West

Indianness in the institution,” he said, and it is expressed

as well at graduation time.

“I have sat and listened to valedictorians at all our

graduations and when you hear some of the valedictorians

speak, still speak, of the extent to which it is a West Indian

experience, it really does my heart good.”

In spite of the spread, he said the experience of the

students in their formative years is “leading a lot of them

toward the belief that they belong to a regional entity.”

“So I applaud the effort of the present Vice-Chancellor

when he says there is one UWI, and I point out that we have

always had one UWI, so how I interpret that initiative is to

make some of the structures, the processes to facilitate the

oneness – cause you’re not creating one university, there’s

never been anything but a one university – but I make the

point that you are trying to create the structures that will

facilitate that oneness. That is how I have interpreted this

initiative which is being put forward. And I am all in favour

of having structures and processes in place that will facilitate

this oneness of the institution.”

One of the concerns about educational institutions

is that the focus is on certification and students do not

demonstrate the kind of civic-mindedness so vital for the

development of the region. Sir George feels that by the time

students enter The UWI, their characteristics are already

formed by their environments and culture, and it would be

tough to reshape them radically.

“That is very difficult,” he said, “Yet we cannot dissociate

ourselves from the responsibility to try to inculcate some of

the values that would lead to a better citizen.”

He has heard many good reports about graduates,

particularly from his medical community, and he stoutly

defends the quality of the students generally.

“I’ve heard the comment being made on many

occasions about our graduates not being job-ready when

they come out. I think that is absolute nonsense. I say no

graduate will ever be job-ready. None. What we hope is that

they will be job-prepared, to have the basic skills, attitude,

competence to adapt to the job they’re going to do.

Every good employer has a responsibility to help the

person who comes in to adjust.

I believe this is something we should push back hard

on,” he says indignantly.

It is a measure of how strongly he feels because he is

characteristically unflappable.

As we wound up, I asked him what he thought was

his legacy, and his response was immediate and emphatic.

“I shall never answer that. You know why? Because I

always believe it is arrogance to say that you leave a legacy.

It is for other people to say what they think of what you’ve

contributed. I think it is pompous arrogance. My legacy is

so and so. I never answer that. No one ever does anything

alone. If I say I am pleased to have contributed, and I use

the word contributed, because you could not do it unless

you have support.”

It was the position he took in a speech he gave at Mona

in 2005, which he called Listen to the Chimes of the Bell,

where he celebrated the growing number of students coming

from the poorer stratum of the society as a sign that “we

have moved frombeing the university of the elite to become

the university of the many.”

Andhe threwout a question, andoffered anobservation.

“How do we maintain excellence and at the same

time, increase access? I have found that there is remarkable

commonality in the requisites for personal and institutional

excellence. There is self-discipline, the capacity to listen

and hear, and avoid the sinister hubris. Perhaps the most

difficult is the capacity for honest self-criticism, the

acknowledgement that you can and will be wrong often

and the understanding that the seal of excellence is never

given by one’s self.”

They are words that resonate with wisdom and grace

– the mark of a man who has done The UWI the honour of

being its Chancellor.

Vaneisa Baksh is editor of UWI TODAY.

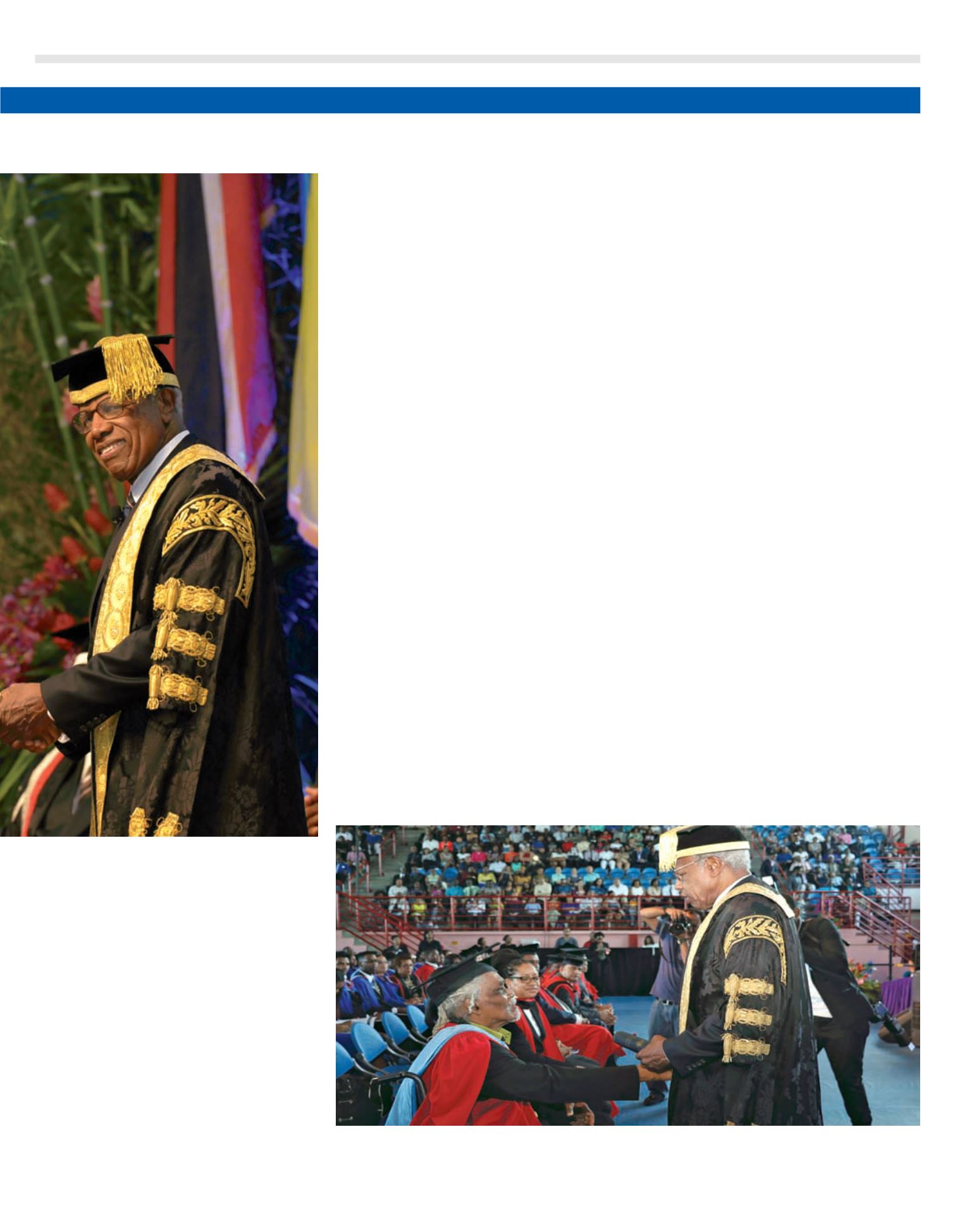

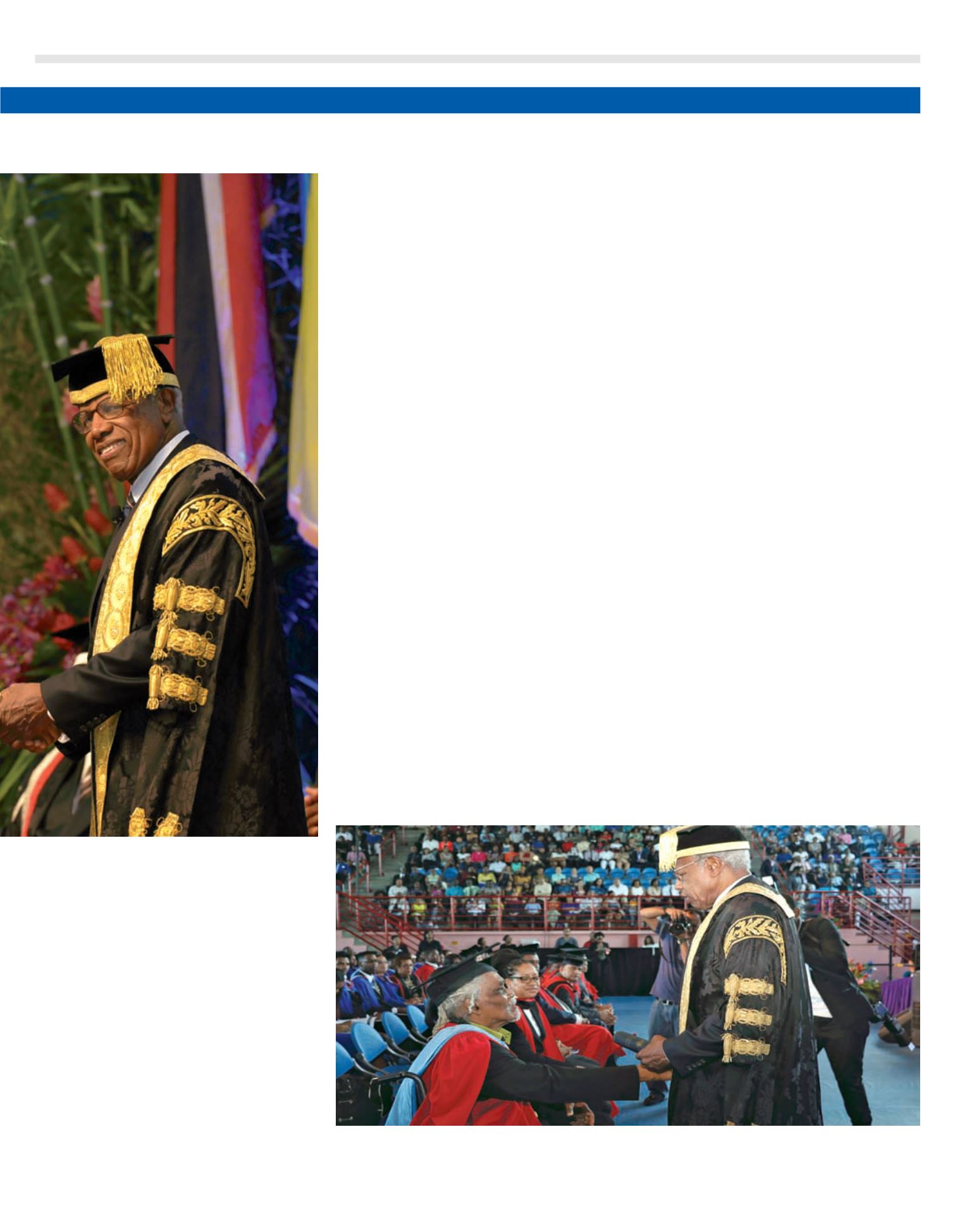

Former Chancellor Sir George Alleyne is well known as a stickler for doing things by the book, but always with grace and good humour.

Presiding over his final round of graduation ceremonies last year, he stepped off the platform to present the scroll to Mr Anthony Williams,

ORTT, who was conferred with the Honorary Doctor of Letters by The UWI. The pan pioneer, who also contributed to the Percussive Harmonic

Instrument (P.H.I.), was unable to mount the stage.

PHOTO: ANEEL KARIM

ng

S A B A K S H