SUNDAY 22 JANUARY, 2017 – UWI TODAY

7

RESEARCH IN ACTION

Have you ever heard

of the world-famous local fish called

Poecilia reticulata

? Youmay know it as the guppy, canal fish,

seven colours or millions. Many know this tiny fish from

hours of childhood fishing pleasure, or as an aquarium pet.

The Trinidadian guppy is famous because it is sold in many

countries as an aquarium fish, it is the focus of research

by many scientists abroad, and it has been introduced to

many countries to control mosquitoes since it eats mosquito

larvae.

Mosquitoes are a nuisance and threaten human health

because they are biting insects that feed on human blood,

and they are vectors, or carriers, of several life-threatening

diseases such as dengue, yellow fever andmalaria.The recent

spread of these and other mosquito-borne diseases, such as

Chikungunya and Zika, spurred renewed efforts to control

mosquitoes. One popular method is to introduce larvae-

eating fishes, such as guppies, to water where mosquitoes

breed in the hope that they will eventually reduce the

number of adults.

As recently as 2013, guppies were released into fresh

water in Pakistan to fight a dengue epidemic. In 2014, school

children and volunteers joined the

Guppy Campaign

, a

programme that released guppies into puddles as a means

of fighting malaria. And in 2015 and 2016, they were used

in Brazil to control the spread of Zika and dengue. Perhaps

because of the familiarity and ease of using this approach,

there were reports of people independently releasing guppies

in disease-affected countries. A search for “mosquito

control guppy” in Google produces hundreds of articles

and websites promoting this approach.

But among these you will also find an article recently

published by my colleagues and I, casting doubt on the

effectiveness and wisdom of using this strategy.

Guppy Campaign

volunteers use a simple effective

strategy to convince others that guppies will eat mosquito

larvae – jars of guppies eatingmosquito larvae.The problem

with this, and similar experiments showing that guppies

eat mosquitoes is that the fish had no other food available.

There is strong evidence that guppies prefer other foods.

In experiments in which guppies were given mosquito

larvae and other foods, the guppies ate more of the other

foods. The faeces of guppies caught in the wild showed that

guppies in nature ate even fewer mosquito larvae than in

the experiments. Here in Trinidad, we observed that guppies

feed extensively on mosquitoes when they are in planters

of stagnant water, but not when they are in moving waters

or their natural settings. They also eat fewer mosquitoes

in polluted water, probably because of the wider variety of

foods available.

So, it is not that guppies do not eat mosquito larvae –

they do – but it seems that they much prefer to eat other

things, and will only eat a lot of mosquitoes when other

foods are scarce. In other words, guppies may not be as

effective in controlling mosquitoes as we think.

So, why may introducing guppies to guppy-free areas

not be wise?

Chances are that the introduced guppies will be released

into the wild or escape, for example, through flooding, or

young guppies can hitch a ride elsewhere on birds or other

animals. Guppy entry to any site is highly likely to result

in the fish establishing a population that thrives in its new

home. Guppies have become established in at least 69

countries outside of its native range, and use for mosquito

control is implicated in about 60% of these cases. Escapees

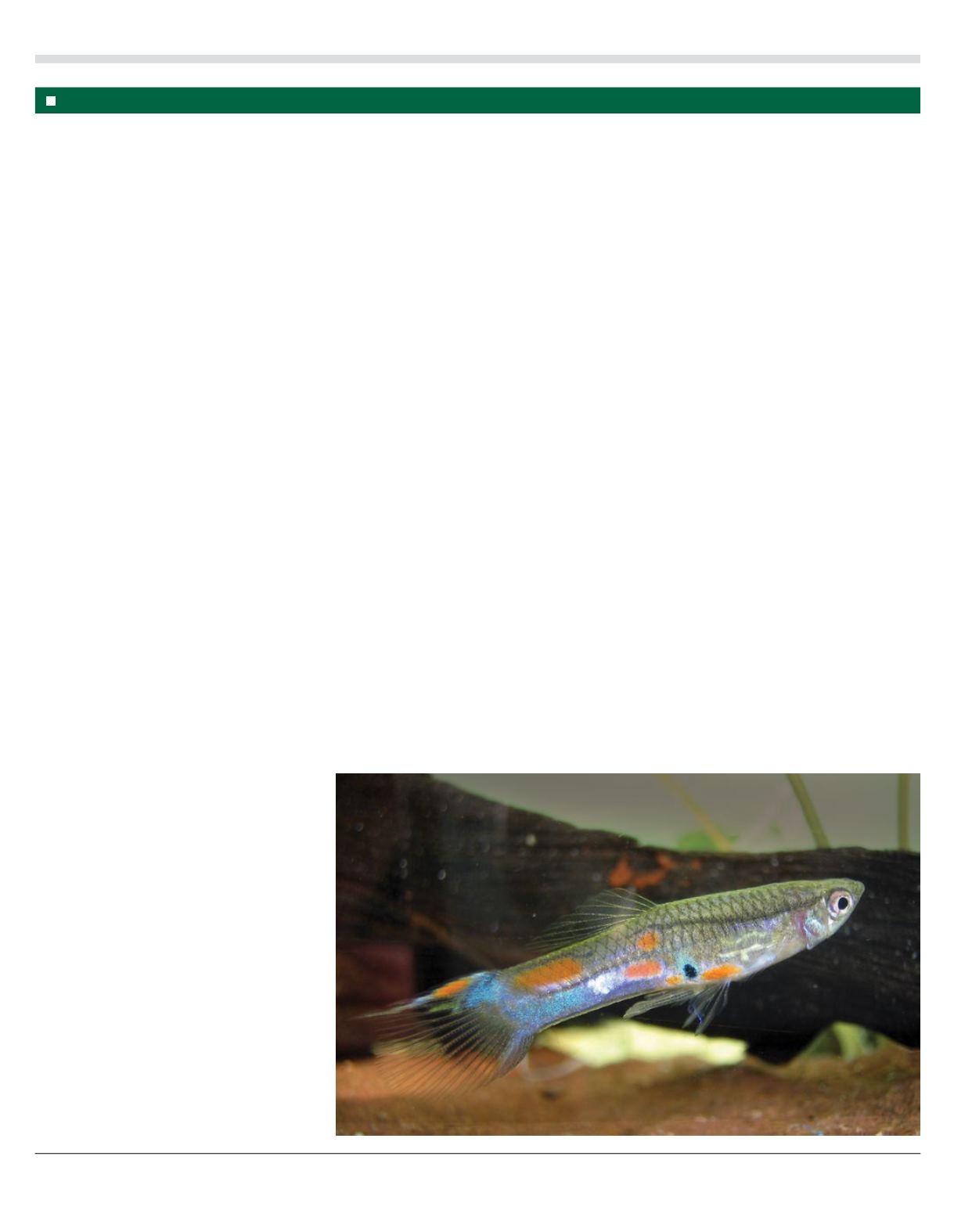

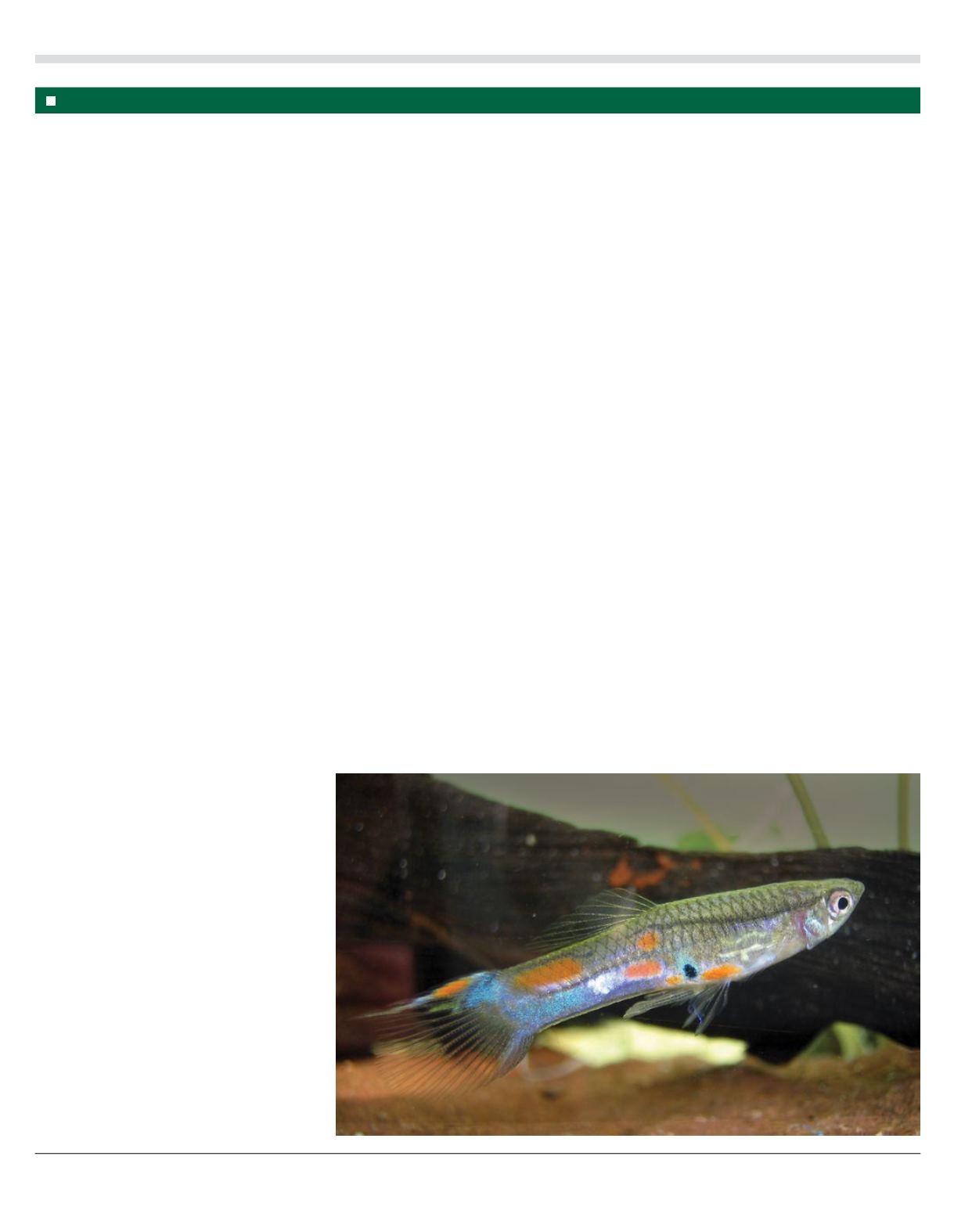

Male Guppy, collected in Tobago waters.

PHOTO: RONNY LUNDKVIST

Dr Dawn Phillip is a Lecturer in the Department of Life Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, UWI St Augustine

can easily establish new populations because of the very

characteristics that make them attractive for pets, research,

andmosquito control – they are hardy little fishes that easily

adapt to new conditions, reproduce often, give birth to

young fish, and grow and start reproducing quickly.

Guppies can tolerate and quickly evolve in a wide

range of conditions. They are found in small ditches,

drains, ponds, streams and lakes, in clear or muddy, fresh

or brackish water, in temperate to tropical countries. They

can be found in polluted water, for example, the drains

along the Priority Bus Route, sewers and oil-contaminated

streams. A mated female can store sperm for months, and

use them to fertilise several batches of her eggs. Females

collected from the wild are almost always pregnant, and this,

plus their high adaptability, means that a single pregnant

female has more than an 80% chance of starting her own

successful population if introduced to a new environment,

producing her first batch of young about 28 days after the

eggs are fertilised.

Guppies alter the streams into which they are

introduced. Guppies introduced to previously guppy-free

parts of streams in T&T competed with resident species

for resources, eventually reducing the diversity of local

fishes to become the most abundant species. They changed

the biology of the remaining fish species, by altering their

reproduction, growth, survival, and hence density (that is

,

the number of individuals in an area).

In countries beyond their native range, the effects of

guppy introduction may be more pronounced. In Hawaii,

poeciliids

(guppies and their cousins), introduced since the

1920s, were found to be 10–30 times more numerous than

native fishes. Some native fishes have disappeared from

these areas. Guppies also increased the amount of benthic

biofilms (the slippery coating on rocks, plants and any solid

surfaces in water, that are composed of diverse and complex

community composed of algae, bacteria, fungi and other

microorganisms embedded in a complex organic matrix).

They also increased the abundance of benthic invertebrates

such as insect larvae and worms, but this was uneven across

species so that some actually decreased while others became

more abundant. At least one alien invasive insect became

more abundant in the presence of guppies.

Because each species affects its environment in different

ways, these changes at introduced sites translate into other

changes in the way these stream ecosystems function. One

important feature is the cycling of nutrients such as carbon,

nitrogen and phosphorus, as this helps ensure that these

important building blocks for organisms are available in

forms that they can use. Guppies have increased available

dissolved nitrogen by up to eight times compared to areas

without them, and total organic carbon by up to five times.

What does this mean? Consider the biofilm as an

example: biofilm communities play critical roles in aquatic

environments. They help cycle nutrients, and supplying

energy and organic matter to other stream organisms. They

are sensitive and respond to changes in nutrient availability,

generally increasing in thickness and extent in response to

increases in nutrients. In extreme cases, they can develop

those unpleasant green or grey-green mats commonly seen

in neighbourhood drains.

So what should be done to control mosquitoes? We

recommend against using guppies on a large scale, as

they may be ineffective, and have significant risks to local

ecosystems and their biodiversity. Instead, more effective

methods (for example, mosquito nets or window screens)

should be used. Where guppies are deployed, this should be

done inwell-controlled settings, and be carefullymonitored.

There is a lot of information on biological control that can

be used for guidance on best practice, but we strongly

recommend that research into the use of guppies to control

mosquitoes needs tomerge the medical, health and ecology

and evolutionary sciences.

CONTROLLING THE

BIO-CONTROL

B Y D AW N P H I L L I P

“So, it is not that guppies do not eat mosquito larvae – they do – but it

seems that they much prefer to eat other things, and will only eat a lot of

mosquitoes when other foods are scarce. In other words, guppies may not be

as effective in controlling mosquitoes as we think.”