12

UWI TODAY

– SUNDAY 10 SEPTEMBER, 2017

FILM

Jeanette G. Awai is a freelance writer and marketing and communications assistant at The UWI St. Augustine Marketing and Communications Office.

“I hope you enjoy this movie

and it speaks to you, but I

want you to pay attention to the credits.” Trinidad-born,

Canadian-based producer, Selwyn Jacob cautioned the

packed Centre for Language Learning (CLL) Auditorium’s

audience before the screening of the documentary,

Ninth

Floor

on July 20. The atmosphere in the auditorium buzzed

with anticipation as unceasing rows of patrons flowed into

the auditorium, forcing hosts, the Department of Literary,

Cultural and Communication Studies (LCCS) and the

trinidad+tobago film festival (ttff) to create makeshift

seating and additional accommodation.

The event’s large turnout was unsurprising, given the

unfortunate relevance of the 50-year-old subject matter

– the violent racial conflict surrounding the then, Sir

George Williams University (now Concordia University)

student-led protests in 1969 Montreal. The film recounts

this watershed moment in Canadian history, dubbed the

Sir George Williams affair, where more than 100 students

peacefully occupied the ninth floor of the Henry F. Hall

Building in an act of civil disobedience against the university

administration’s decision regarding a complaint of racism

that had been filedmonths earlier by six Black students from

the Caribbean.The “undersigned six” charged white biology

professor Perry Anderson with racial discrimination and

biased treatment as compared with their white counterparts.

Under the direction of Mina Shum, the film reveals

how the Caribbean students came into black consciousness

through their racist experience. Jacob uses archival footage

to highlight the institutional racism within the University

as white professors came up with a rubric for differentiating

betweenWest Indians and Afro-Canadians with stereotypes

such as, “West Indians laugh immoderately, are frequently

obscene and don’t take much at face value.” The crowd

laughed in response to this comical description – a rare

moment of levity in the 82-minute film which hammers

home how traumatic the ninth floor occupation was to

the Caribbean students involved. The students locked

themselves in the Computer Centre located on the ninth

floor as an act of peaceful protest against theAdministration’s

mild punitive suspension of Perry Anderson. This went on

for a few days and on February 11, everything escalated.

A fire broke out in the data centre resulting the students

hurtling hundreds of computer cards and other documents

through the windows, “like snow out of heaven onto the

brains of society scattered in the wind,” according to one of

the survivors in the film. The students’ cries for help were

met with police and riot squad officers who stormed the

computer room, arresting 97 people, whites as well as blacks.

The importance of Jacob’s mandate to focus on the

names mentioned throughout the documentary becomes

evident as their lives after the incident becomes the real focal

point of the film. He admits, it has been his life’s work to tell

this story ever since he was a young man considering going

to university in Canada, “I always knew that I would tell

this story – I had been saddled with the good-for-nothing

perspective; these good-for-nothing students came up here

and destroyed the people computer. Don’t be like them.”

The audience got to see “them,” not as a static names in a

newspaper report, but as three-dimensional people who

HISTORY REVISITED

What happened after the fateful Ninth Floor occupation in Montreal

B Y J E A N E T T E G . A W A I

survived. Names like Terrance Ballantyne and Hugo Ford –

two of the original six students whose complaint led to the

riot. TheWest Indian students who would later be involved,

include Valerie Belgrave, Bukka Rennie, Rosie Douglas,

who was imprisoned and then deported and later became

Prime Minister of Dominica. Anne Cools, originally from

Barbados, who went on to become the first Black Canadian

to be appointed to the Senate, and Rodney John has had a

distinguished career as a psychologist and several others.

Persons like Kennedy Frederick – who was shown only

through his clips of his incendiary younger self as a fearless

catalyst for the occupation. Sadly, he never recovered from

the events of 1969 and was forced to go into hiding and

throughout the years since, he suffered a host of mental

illnesses. He is the film’s reminder of the hidden price one

pays for being on the right side of history. In 2017, it’s easy

to forget that the social activismhad a negative connotation.

Jacobs stressed that although, he wanted to havemore voices

in his film, “some people didn’t want to be found because of

the stigma attached. People changed their names, moved to

the US...some disappeared.”

The film night ended on a more optimistic note with

Jacobs encouraging the audience to applaud the courageous

students involved in the incident some that were present that

night like Terrance Ballantyne. Like a teacher addressing

his students, Jacobs advised, “The film is really about these

people – they made a decision at a certain point in life and

were stigmatized, but they overcame.”

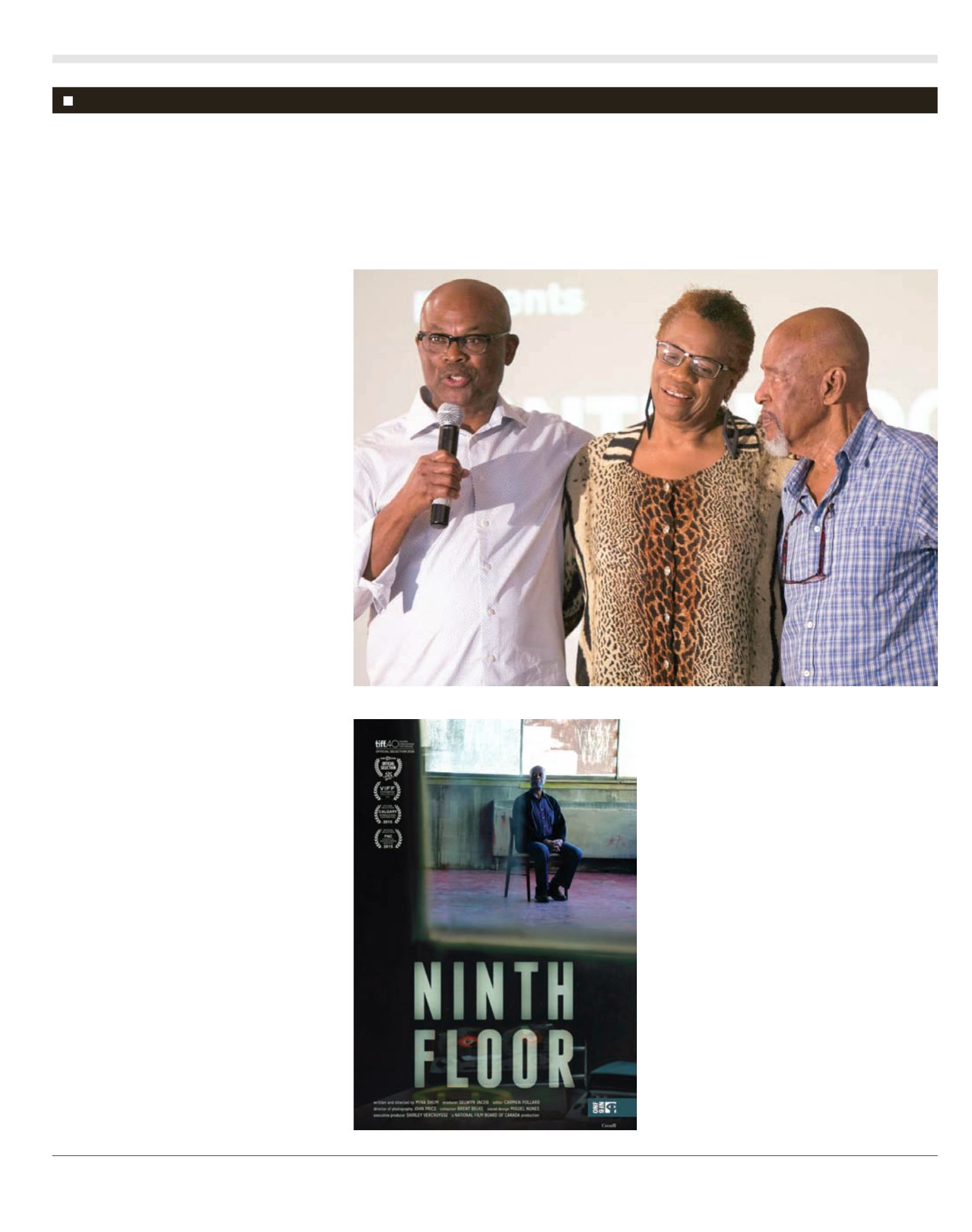

Selwyn Jacob, Lynne Murray and Terrance Ballantyne at the screening of Ninth Floor.

DIGIMEDIA PHOTO & CINEMA, COURTESY TTFF