|

|

|

|

February 2010

|

Social insects in the scheme of island life

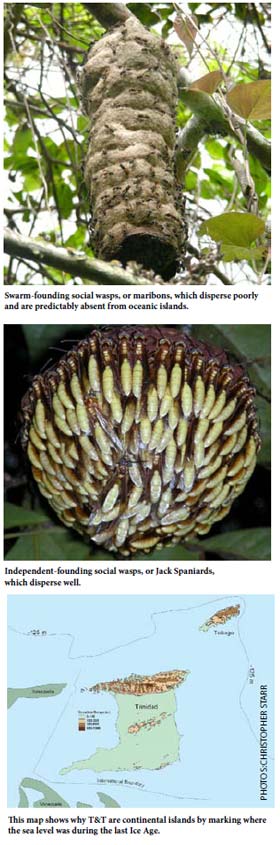

Social insects are that peculiar minority (about 1-2%) of species that live in durable, structured groups known as colonies. Everyone is familiar with at least a few species of social insects. You have certainly noticed the abundant, dark-brown termite nests that adorn many trees (and you may on rare occasions be chagrined to find these or other termites invading your house). Jack Spaniards are among the social wasps that you have learned to respect (if not necessarily to love). Some bees, including the much appreciated honey bee, have highly-developed social organization. And ants, such as the bachacs that you can see in your garden every night, seem to be everywhere. Life in a colony is a very different matter from that of solitary insects. For one thing, it is a cycle of almost constant interactions among nest mates. For another, there is a more or less striking distinction among different kinds of individuals (known as castes) according to their roles. The primary caste division is between the few reproducing individuals (queen and king in termites, queens only in all others) and the non-reproducing workers. For a biologist, life in an archipelago has an extra dimension that can make it extremely attractive. Each island is, in a sense, a world of its own, and the distribution of plants and animals among islands is a source of endless questions, answers and fascination. Island biogeography draws on a key distinction between two types of islands. Continental islands are those with a previous dry-land connection to a continent. Trinidad and Tobago were once parts of the South American continent, isolated by rising sea levels an estimated 14,000 (Tobago) and 10,000 (Trinidad) years ago. The rest of the West Indies—the Greater Antilles and Lesser Antilles—are oceanic islands, without such a previous connection. While Trinidad and Tobago began their island existence already with a full complement of plants and animals, then, the Antilles started out with nothing and have only become populated by species that could cross stretches of open sea. My own particular interest is in the comparative diversity of social insects on islands. If two islands have much the same habitats, the larger one is expected to harbour more species, whether of social insects or anything else. The relationship is conventionally expressed as S = kAz or log S = log k + z log A, where S stands for number of species, A is the size of the island or other area, and k and z are constants. The constant of interest is z, which defines how rapidly the number of species (species richness) rises with increasing land area. This is best seen in a double-log graph, in which z is the slope of the line. Studies of different groups of organisms in various parts of the world show that z tends to be between 0.25 and 0.35. However, continental and oceanic islands are plainly not comparable in this regard. In any given group of plants or animals, an oceanic island will almost always have fewer species than a continental island or a part of the continent of the same size. We can illustrate this by reference to social wasps. The second graph shows the species-area relationship for islands of the West Indies and some continental areas of Central and South America. Two things are apparent in this pattern. First, continental areas and islands have markedly more species than do oceanic islands of similar size. You will note, for example, that Trinidad has several times as many species as does (oceanic) Jamaica. Second, if we plot the slopes of the two groups separately we find that they are both very similar, slightly over 0.30 in each case. There is more to biotic differences between continental and oceanic islands that this difference in species richness. Not all species are equally able to cross sea barriers and establish themselves on oceanic islands. For example, it is not surprising that bats are much better represented on such islands than are non-flying mammals, relative to their numbers on the continents from which their ancestors emigrated. And large mammals, like deer and quenk, are virtually absent unless introduced by humans. This pattern of differences in composition is known as disharmony. Unlike solitary insects, social insects seldom disperse to new areas except in the course of founding new colonies. This process takes different forms in different species. In Jack Spaniards, for example, a single queen can found a new colony. Dispersal from the mother colony, then, is limited only by how far a wasp can fly (or be blown by the wind) by herself. In the other main group of social wasps, maribons or marabuntas, in contrast, it takes a group of several queens and many workers to start a new colony, and the group must remain intact, so that maximum dispersal distance is necessarily much less. Not surprisingly, while Trinidad and Tobago are home to about equal numbers of species of the two groups, the social wasps of the Antilles are almost exclusively Jack Spaniards. In fact, only one maribon is found in any of the Antilles and only in Grenada. The various testable predictions arising out of this hypothesis are largely corroborated by results from the West Indies, with one striking exception. I predicted that the higher termites (family Termitidae) would be better represented than the lower termites (all other families) in the Antilles, relative to their numbers in northern South America. I reasoned that the overall greater size of the flying queens and kings and the huge numbers that emerge in the founding season would make them more likely to cross sea barriers to new islands. It was a fair prediction but, in fact, exactly the opposite is true. The lower termites are much more prevalent up the islands. The most likely reason is that their colonies have a much greater chance of being carried on floating logs, an accidental process quite different from normal colony founding. It is my firm conviction that social insects are the most interesting feature of the known universe. Islands make for some of the world’s most interesting places. Together they are an irresistible combination. -Dr Christopher Starr is a Senior Lecturer in Entomology, at the Department of Life Sciences, UWI, St Augustine.

|

By Dr Christopher Starr

By Dr Christopher Starr