By Professor Pathmanathan Umaharan

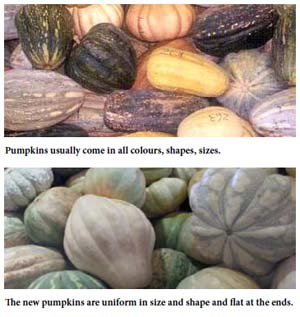

When square watermelons hit the market some years ago, it caused a stir. The novel pumpkins were re-shaped for packaging purposes—many more could fit into boxes—which reduced production costs. Not to be outdone, local researchers at the Central Experimental Station, Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources (MALMR) have developed a pumpkin variety that bears uniform 20-25 pound fruits, globular in shape, but flattened at both ends; and attractively coloured brilliant peach to orange when ripe. When square watermelons hit the market some years ago, it caused a stir. The novel pumpkins were re-shaped for packaging purposes—many more could fit into boxes—which reduced production costs. Not to be outdone, local researchers at the Central Experimental Station, Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources (MALMR) have developed a pumpkin variety that bears uniform 20-25 pound fruits, globular in shape, but flattened at both ends; and attractively coloured brilliant peach to orange when ripe.

Unlike the square watermelons, which were obtained by meticulously placing each fruit into a square plastic box (a time-consuming task) and allowing them to grow within the confined space, these pumpkins’ shape and size were developed through genetic manipulation.

“This allows pumpkins to be readily packaged into the packaging bags and boxes used for export,” said Albada Beekham, the researcher who headed the pumpkin breeding programme at MALMR. “The flattened top and base allows the uniformly sized pumpkins to sit snugly on top of each other in a cylindrical bag.”

At the research seminar series of The UWI’s Faculty of Science and Agriculture in early December 2009, she explained that the work was prompted by a market study that showed the large variability in size, shape and colour within local pumpkins was a major deterrent to international marketing.

“Breeding was the most practical way of solving the problem,” she said. The breeding of the new variety has been a long and arduous journey, particularly in a crop such as pumpkin, which needs considerable space to plant the large number of progeny plants, but it has been worth the effort. “Breeding was the most practical way of solving the problem,” she said. The breeding of the new variety has been a long and arduous journey, particularly in a crop such as pumpkin, which needs considerable space to plant the large number of progeny plants, but it has been worth the effort.

“It will not only add value to the product, but also reduce shipping costs,” said Beekham. “All of this has been achieved without compromising the yield or quality.”

The area under which pumpkin is grown in Trinidad and Tobago has fluctuated between 600 to 1500 ha during the past decade, with the production volume varying from 2-5 million kg, according to figures from the Central Statistical Office. Most of the pumpkin produced is exported. The export volume during the past decade has fluctuated between 1-4 million kg, bringing in revenue of TT$ 8-15 million. Most of the pumpkin is exported to the USA, according to NAMDEVCO.

The local pumpkin belongs to a species called Cucurbita moschata L. (moschata pumpkin), which is distinct from the North American pumpkin, which belongs to a species Cucurbita maxima L. Moschata pumpkin is believed to have originated in Columbia and has a distribution spanning Venezuela, the Guianas and the Caribbean. Despite the considerable variability for the species within the Caribbean, moschata pumpkins have largely remained unexploited.

“Moschata pumpkins show considerable variability from “the warty Crappo-back to the smooth types; the heavily grooved to non-grooved; the round shaped to acorn, flat or elongated; the peach-coloured to yellow, orange, black or blotchy and small through to extremely large. There is also variation in internal texture, fibrousness, sweetness, colour and smoothness upon cooking, etc,” said Beekham. “Breeding is about capturing the variability to fashion new varieties.” “Moschata pumpkins show considerable variability from “the warty Crappo-back to the smooth types; the heavily grooved to non-grooved; the round shaped to acorn, flat or elongated; the peach-coloured to yellow, orange, black or blotchy and small through to extremely large. There is also variation in internal texture, fibrousness, sweetness, colour and smoothness upon cooking, etc,” said Beekham. “Breeding is about capturing the variability to fashion new varieties.”

As to the future of the pumpkin variety, Beekham, is very optimistic. She hopes that MALMR will soon apply for variety protection under the Plant Variety Protection Act, which will give it exclusive rights to produce and market the variety or to license the variety to a third party to produce and market.

“The MALMR can possibly commercialize the variety in Trinidad and Tobago and beyond,” she concluded.

The MALMR’s efforts to continue important developmental work despite the odds, need encouragement and support. More importantly, these are innovations based on which sustainable industries can be built, and should be taken seriously. Often as a nation, we look for illusive Nobel prize-winning discoveries, while ignoring the small innovations that are taking place all around us. As one of our calypsonians put it: “the journey now start.”

The ball is now in the court of the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources to take this innovation to the market.

Pathmanathan Umaharan is Professor of Genetics at The University of the West Indies

|