It is mid-morning on campus and Professor Pathmanathan Umaharan, Head of the Cocoa Research Centre (CRC), is making his way across to the engineering labs. He is going to see about a machine. Seems a mundane enough trip, a ten-minute walk through the campus grounds from the Agriculture Faculty to Engineering; but this is only one stop in an enormously important journey, years in the planning and years still from its destination.

The machine, a final-year project of mechanical engineering student Sayeed Khan, automates the process of splitting cocoa pods and extracting the seeds. It’s a crucial step in the cocoa cultivation process and one that has remained little changed over its history.

“In cocoa production, none of the procedures have been mechanised,” Prof Umaharan says. “Everything is done manually in a traditional way.”

And for the reinvigoration of an industry that has been on the decline for many decades, in part because of a dwindling labour pool, that must change. The CRC sees innovation-driven mechanisation as a potential catalyst for this change – and a much wider and more ambitious transformation. Partnering with the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering (MME), they are working towards creating a robust cocoa sector, from cocoa production to chocolate manufacturing, powered by regionally developed and constructed equipment and machinery.

The goal is audacious, but perhaps even more exciting is the strategy being used to achieve their objective. Faculties are coming together and fostering an innovative culture within the university, with the purpose of finding solutions to some of the region’s challenges in the areas of food production, economic diversification and value-added exports.

“The whole nation (Trinidad and Tobago) has been crying for diversification away from oil and gas,” says Rodney Harnarine, Development Engineer in MME. “This is one area where there is a real opportunity. If we can move and grow this opportunity in agriculture and agro-processing we are creating jobs. It is a win-win situation for us.”

Harnarine, like some of his colleagues within the Faculty of Engineering, has been an unyielding advocate for applied innovation, particularly in the area of food production. He is also a major facilitator of the growing culture of innovation within MME (see A Secret Garden of Ideas, UWI Today, April 2015 http://sta.uwi.edu/uwiToday/archive/april_2015/article11.asp).

Innovation, food production, economic diversification – there is almost no way to over-emphasize how important these three are to the long-term wellbeing of the Caribbean, or to the planners with responsibility for the region’s future. Whether the project succeeds or not, this remarkable example of inter-faculty collaboration is an outstanding model for how UWI can interact both with itself and the societies it was created to serve.

Potential in a pod

“Three years ago Prof Umaharan approached us to build equipment for the cocoa industry because they had problems with labour,” says Harnarine over the din of machinery at the Strength of Materials Laboratory of MME.

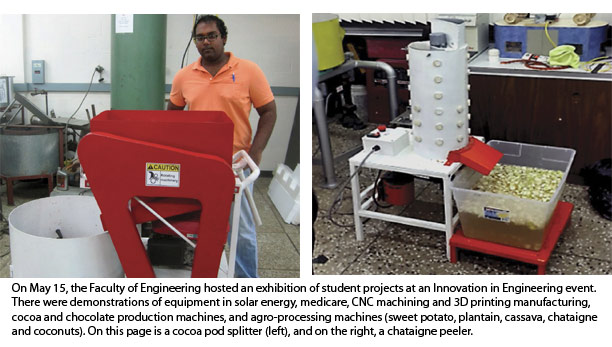

The department was hosting an informal exhibition of student projects – an array of innovative pieces ranging from advances in agro-processing, to bamboo work, to glass testing and even medical care. Among them were two projects directly related to the work of the CRC – a conche (a device used in the making of chocolate) designed by student Javed Mustapha, and the cocoa pod splitter.

Umaharan explains his interest in the machines:

“Mechanisation, we think, is a way to make agriculture much easier and sexier than how it is at the moment. That is why I am working very closely with mechanical engineering. We want to introduce more mechanisation in terms of pruning, harvesting, cracking the pods, transferring the pods from the field to the fermentation area, and even fermenters. We use mechanical fermenters that can accelerate the rate of fermentation and improve its quality.”

MME has already developed a prototype automated fermenter for CRC under the supervision of Dr Graham King. The centre is also working with Dr Saheeda Mujaffar in the Department of Chemical Engineering to develop an artificial drying method for cocoa.

A Caribbean Cocoa Model

Home to the high quality Trinitario variant of cocoa bean, investment in cocoa as a primary product makes sense in Trinidad and Tobago. But even though increasing agricultural production is crucial for the development of a sector that can make a significant impact on GDP, the real gold is in cocoa as a source of manufactured products.

“If you sell cocoa at the current price of TT$20 per kg, somebody takes that and manufactures chocolate and that product is then multiplied by 200%. So that person benefits from our labour, whereas if we could add the value here we would benefit,” explains Harnarine. “This is where we need to go – add value to our crops.”

Trinidad and Tobago has already developed an enormously successful value-addition model in its energy sector. It was a pioneer in using its natural gas as the foundation of an extensive and highly profitable value chain that extended from discovery and production, through refining and downstream manufacturing. Along the way, the value of its natural resources has multiplied, a host of new industries have sprung up and many more people have found employment in a well-articulated energy sector.

Strategic thinkers like Umaharan and Harnarine want the same for cocoa. And once again, innovation can help.

“The CRC has a small chocolate factory that produces chocolate and trains persons from the sector in chocolate making,” says Umaharan. “Over the last two years we have trained over 100 persons but when they need machinery and they see the great expense to buy and import the machinery themselves, they have not been able to get into chocolate making.”

He adds, “that is where this linkage (with MME) becomes so important. We can use the linkage to make the equipment here cost effectively and really jumpstart a chocolate industry instead of exporting cocoa as a primary product.”

The conche on display at the MME exhibition is one example of a locally developed machine for the manufacture of chocolate. In the chocolate making process, the conche is the seventh step (see “Chocolate in Stages”) – heating, aerating and kneading the chocolate as well as calibrating the flavouring system. However, many local manufacturers do not have access to a conche and are forced to improvise.

“Currently local chocolate makers improvise with a melangeur to perform the functionality of the conche,” says Mustapha about his project. “There is no heating element present in the melangeur, which is crucial for removing volatile compounds.”

In other words, a locally manufactured conche could enhance the quality of chocolate made in the region while avoiding the prohibitive costs of purchasing and importing a foreign brand.

Like his designs for cocoa production, Umaharan’s vision for chocolate making is expansive.

“We have a whole range of equipment that we are working on. We need roasting machines. We need machines to do grinding. We need machines for tempering. There are lots of small pieces of equipment that go together in making chocolate so we are looking forward to working with the Mechanical Engineering department so that we have a complete range of equipment. People can come and one-stop shop. They can buy the whole outfit to get their chocolate factory going.”

Though they will take much time and effort to be achieved, the CRC’s objectives for the cocoa sector are worthwhile and ambitious. The strategy to get there however, is already in play, and it is valuable in and of itself. UWI students are being encouraged to pursue innovation to meet the specific needs of the society. In one project the university is meeting its mandate to be relevant to its stakeholders by fostering a culture of innovation and working towards the growth of an economic sector.

Already, the CRC has plans to put the cocoa pod splitter in the field in the hands of farmers to see how effective it is.

“We want to put it in the farmer’s fields so that when they operate it we can see if they have any problems and we can adapt and change,” Umaharan says. “That’s how innovation happens. We have some thinking about how the device should work but when the farmer uses it he can say ‘ok, you need to modify it this way so that it can work better.’ We are looking forward to putting it out there and getting feedback. Once it works in one farm it could work in all the farms.”

Harnarine, himself an innovator, is hopeful for the growth of the cocoa sector but mindful that it will take time.

“The public must be patient and understand these are students. It took me three years to go from idea to machine (for his automated bread nut/chataigne peeler). The idea takes time to grow and iron out the bugs. But we will work on it and sometime soon you will see the results.”

But all signs point to the cocoa sector being well worth the wait. In the words of Prof Umaharan:

“Cocoa has one of the greatest potentials for Trinidad because we have research going back for about 82 years in cocoa production. We have excellent variety. So if we can combine those things with more innovative ways of production then we could really make agriculture more productive and attractive to the farmer. And once it is profitable to the farmer and we link it to the value-addition process, we have a complete business sector evolving around cocoa which creates employment and opportunities for export.”

No, not your everyday campus stroll.

- Harvesting – The cocoa beans are harvested. There are three types of cocoa beans – criollo (premium bean), forastero (the most common bean) and trinitario a rare hybrid of the two varieties produced in Trinidad and Tobago.

- Fermentation – The beans are fermented between 4 to 7 days

- Drying – The beans are dried to stop fermentation (turning brown in the process).

- Roasting – The beans are roasted at between 230F and 428F for 40 to 50 minutes to develop chocolate flavour.

- Blending, Grinding and Mixing – Beans are custom blended according to manufacturers requirements. They are ground into a liquid mass called “chocolate liquor”, a combination of cocoa butter and cocoa solids. At this stage sugar, milk, vanilla and other ingredients can be added.

- Refining – The chocolate mass is sheared into smaller particles (about 20 microns). This size is essential to the texture of the chocolate.

- Conching – The mass is heated, mixed and aerated for up to a few days to eliminate any off flavours or unwanted bitter substances. Conching increases the fineness of the chocolate.

- Tempering – The chocolate is heated, cooled and reheated to allow good cocoa butter crystals to form and bad crystals to be eliminated. Tempering results in smooth and glossy chocolate with a pleasant smell and resistance to warmth (will not melt in your hand).

|