14

UWI TODAY

– SUNDAY 5 AUGUST, 2018

BOOKS

IMMORTALISINGKITCH

B Y J A R R E L D E M A T A S

Under a barely-lit night sky,

a star was born on

stage, while a calypsonian’s legacy was re-ignited.

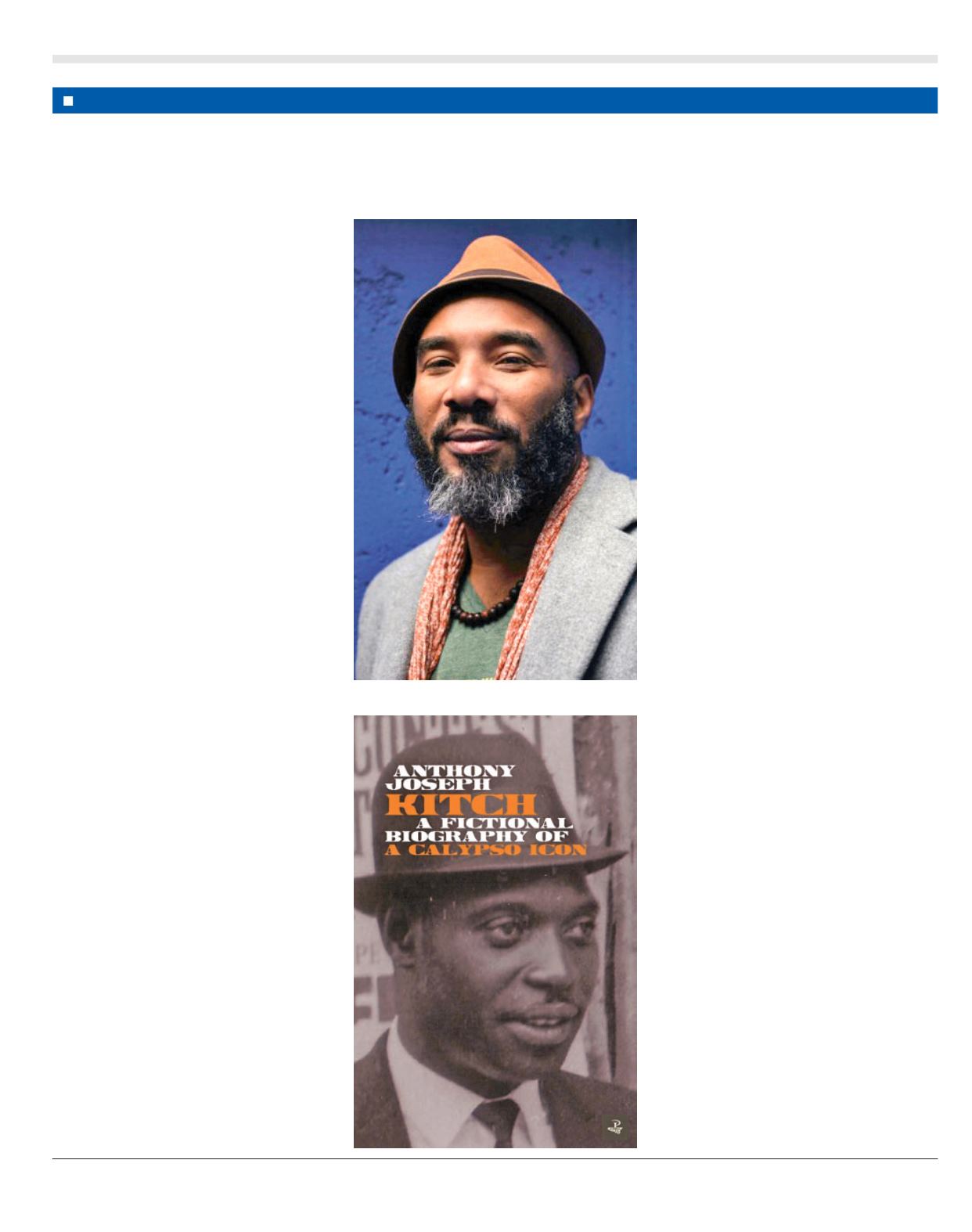

Trinidadian-born, UK-based writer Anthony Joseph

delivered a stellar performance as part of the book

launch of his novel

Kitch

onApril 27.The Big Black Box

was the venue for a roster of imminent and emergent

writers. But it was Anthony Joseph who stole the show.

Endorsed by theNGCBocas Lit Fest, Joseph’s novel

did more than focus the spotlight on his artistic voice,

it also redirected attention to the larger-than-life figure

who embodied the lived experience of a generation,

and whose personality invigorated a nation.

I’m referring to the late Grandmaster, the

calypsonian known as Lord Kitchener, Aldwyn

Roberts. Joseph’s text is a masterclass. I do not think

a Trinidadian novel has ever made a single artist the

sole focus of its literary illustration. It is appropriate

that Lord Kitchener is the first.

Born in 1922, Kitchener’s musical consciousness

had been unavoidably informed by the colonial

experience. He lived through colonialism, post-

colonialism, post-war independence, and was on

the cusp of early Trinidadian modernism. Kitchener

personified the rise and development of the Trinidad

and Tobago nation-state. Arima, Belmont, Port

of Spain and Diego Martin are a few of the places

captured in the novel that, together with uniquely

Trinidadian expressions such as “it have a zwill in the

madbull tail,” “jagabat,” and “vaps,” reinforce the voice

and setting that

Kitch

portrays.

This artist, who defined a generation with his

musical magnificence, was given fresh life on a night

that celebrated music as much as the written word.

Kitch

was a fitting headliner that did not disappoint.

And given the recent controversial statements made

about the Windrush generation, it was timely.

Joseph was prophetic in descr ibing the

uncertainties and insecurities faced by the Windrush

batch of migrants: “And when you land in the mother

country, who you is to the English? You don’t know if

you coming or going, you papers say England but you

born in Trinidad, and you not of the place you reaching

yet – and when you reach you is a immigrant.”

Lord Kitchener left Trinidad in 1948 aboard

the

MV Empire Windrush

to go to the UK. Joseph

paid special tribute to Kitchener’s role as part of that

generation. Describing the moment the ship docks in

England, an extract reads: “But he stands here now, on

the wooden jetty, upright in England, the land he had

imagined for so long.”

A few lines later,

‘Kitch’

delivers one of his most

famous pieces, upon request by the reporter, which

Joseph captures down to even the calypsonian’s

mannerisms:

“Now, may I ask you your name?”

“Lord Kitchener.”

“LordKitchener. Now I’mtold that you are really

the king of calypso singers, is that right?”

“Yes, that’s true.”

“Well, now can you sing for us?”

“Yes.”

“London is the place for me”

(mimics the upright, wood bass)

“London, this lovely city”

(the right shoulder rises, the beat turns down)

“You can go to France or America

India, Asia or Australia

But you must come back to London city.”

Accompanied by live music and vocals of

Kitchener’s classic, “London is the place for me,” Joseph

was met with thunderous applause.

The author’s extensive craft as a poet brings a

unique rhythm and style that makes the reverence of

Lord Kitchener’s characterisation in the novel leap off

the page. This is not your typical work of fiction, or

biography. In fact, the subtitle of the novel – a fictional

biography – sets readers up for a promising journey

into the life of Lord Kitchener that is enhanced with

Joseph’s poetic prose. Interwoven in the text are lyrical

interludes which evoke the nostalgia and musical

genius associated with the almost mythological

persona of Kitchener.

Part of Joseph’s creative brilliance is that most

of what readers learn of

Kitch

is filtered from the

community of people around him. In this way the

myth-making of

Kitch

is sustained. In fact, the

calypsonian does very little speaking in the novel,

which paradoxically increases his presence and impact

further because different people all have their say on

what

Kitch

meant to them..

The novel’s chapters are divided into three broad

sections that trace the development of the legendary

calypsonian: “Bean,” “Lord Kitchener” and “The

Grandmaster.” Each sub chapter is a personal account

of the impact Kitch has had on the people describing

him. The calypsonian’s influence through music is

summed up in the section titled “Centipede, June

1948:” “Fellas does feel sweet when Kitchener open

he throat to sing. Long as he singing, we feel safe; we

eh go dead.”

“The Road” describes him further: “But

Kitch

,

like he put something else in that song. What it is? I

don’t know much about Africa, but if you listen you

could hear like people beating big African drum with

bone in there.”

As a child of the nineties I did not understand how

significant the life and career of Lord Kitchener was to

Trinidad in particular, and the Caribbean in general,

but Anthony Joseph’s performance that night was

something special.The entire audience, young and old,

was captivated by the gravity of Joseph’s literary project.

I myself was so overwhelmed with pore-raising, lump-

in-throat, emotions following the performance that I

was compelled to give Joseph a standing ovation (as did

other members of the audience). For a brief moment,

Lord Kitchener was reincarnated on stage and I was

able to share in the legendary individual who will

forever be immortalised by

Kitch

.

Anthony Joseph has hit a gold mine as it concerns

in-depth biographical explorations of Caribbean icons

through fiction. It is my hope that similar writings

will be undertaken to shine light on other artists who

shared the generation with our very own

Kitch

.

Jarrel De Matas is a postgraduate student, M.A. Literatures in English, at The UWI St. Augustine campus.

Anthony Joseph