|

|

|

|

April 2009

|

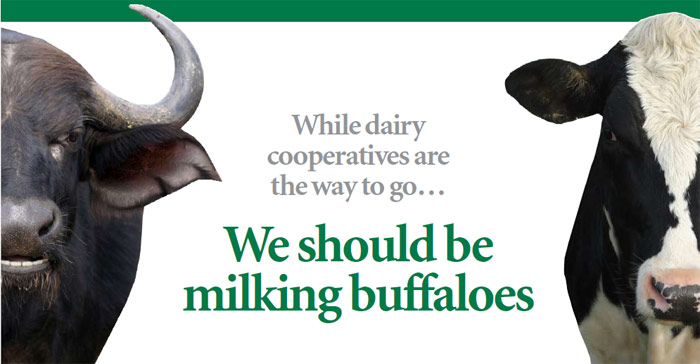

What is the role for cooperatives in our modern economic scenario? After all, have we not embarked on a new economic path in which privatisation, globalisation and liberalisation are the catch words? Why should anyone be concerned with whether or not cooperatives enjoy a progressive legislation? These questions are important not just for the thousands of our small farmers, but for the wider Caribbean. Land is perhaps the most important income-generating asset in the rural economies of Trinidad and Tobago and other Caribbean countries. Yet scarcity of land (particularly freehold) and its skewed distribution are two of the major constraints of the rural Caribbean landscape. Not only is it limited, a large portion consists of holdings other than small farmers’ holdings. Small farmers in the Caribbean, accounting for more than 60 per cent of rural households, have access to only about 30 per cent of arable land. There are approximately 1,500 small dairy farms in Trinidad alone. While various types of farmers’ cooperatives play a useful role in promoting rural development, dairy cooperatives have special attributes that make them particularly suitable. They can facilitate the development of rural economies, thus upgrading the standard of living of the poor and not so poor. The main constraint that milk producers seek to overcome by acting collectively is the marketing of their product. They need to be assured of a secure market. Dairy farmers can cooperatively establish their own collection system and milk treatment facility to convert their perishable primary produce, which requires special and timely attention, into products with longer lasting quality. The Minister of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources understands the importance of dairy cooperatives in bringing about an increase in milk production with simultaneous upliftment of the rural poor. As a first step, the Minister should dispatch a team of five people to study the cooperative milk producers’ organisation in Anand, India. The team should comprise two officials from the Ministry and one each from The University of the West Indies, small dairy-farming community and mediumto- large dairy-farmers’ group. The team’s study tour should be routed through the existing mechanism of the Technical and Economic Cooperation with the Government of India which should be further requested to provide technical assistance to help develop the dairy cooperative movement here in Trinidad and Tobago. The laws concerning the establishment and operation of cooperatives in the country should be reviewed and amended to facilitate setting up dairy cooperatives. The law concerning the definition of “milk” is in urgent need of revision. At present, only cow’s milk is defined as “milk” and only the producers of this milk (and no other types, for example, buffalo, goat, sheep, etc.) are entitled to State’s assistance. The law is strangling dairy development, as cows are not the most efficient/economic producers of milk in our circumstances. For years, I have argued that water buffaloes are better suited to the production of milk and meat than cows under local environmental conditions. There has been limited success, but the Government’s Aripo Livestock Research Station now has a pilot herd of buffaloes for this purpose. However, buffalo milk cannot be sold for money under the present law and thus has to be given away freely. No wonder small farmers are not interested in buffaloes for milk production. Rice farmers should immediately integrate buffaloes into their farming system, utilising the straw to produce meat, even while waiting for the law to be amended to include the sale of buffalo milk, which can be used in the production of ice creams and yoghurt for example, until the taste for it is acquired. Praedial larceny is another important constraint to livestock sector development and the law must be modified to include life imprisonment as punishment. Praedial larceny is no less significant in its economic impact on society than the problem of narcotics and marijuana cultivation and should be treated with the same urgency and resources. A minimum of five to ten years must be allowed for this movement to anchor itself among the grassroots people through education programmes. This means that once a policy on dairy cooperatives is formulated, it must be followed to its logical conclusion, regardless of which political party is in government. The Government should encourage cooperatives as a vehicle for its people-oriented dairy development. There are problems to be addressed, however, including an insufficient number of dairy animals of the right genetic quality; inefficient management; low standards of hygiene on farms; inadequate nutrition of livestock; archaic laws; praedial larceny; and lack of proper leadership. Moreover, since the government is unable to allocate new funds towards expensive imports of heifers from temperate countries of the North, it must give attractive incentives for the implementation of heifer-rearing schemes by private farms initially and the cooperatives later. Significant resources should be channeled to develop buffaloes for milk. At the same time, male calves should be reared for fattening on a feedlot system for the meat industry. These can be fed on agro-industrial by-products such as rice straw, grain-milling industry by-products, and fruit-cannery waste products. Dr Rajendra Kumar Rastogi is a Senior Lecturer, Department of Food Production, The UWI, St. Augustine.

|