|

|

|

|

April 2017

|

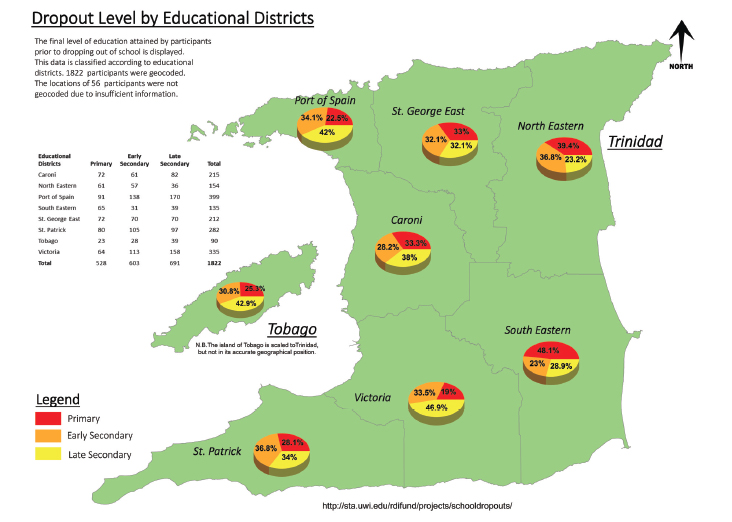

Everyone who has passed through Trinidad and Tobago’s school system knows someone who fell through the cracks. Maybe their home life was less than stable, maybe they had an undiagnosed learning disability, or maybe they just couldn’t keep up with the fixed pace of the current school syllabus. Dr. Priya Kissoon, Head of the Department of Geography, has headed up a team to find out more about the children who ended up dropping out of school throughout the country. Working in collaboration with the School of Education (through Director Dr. Jeniffer Mohammed), the Geography Department spearheaded a national research project on primary and secondary school dropouts (or “early school-leavers”). The project engaged with Government ministries, NGOs and the private sector as they trained and employed nearly 100 community-based surveyors to conduct about 1880 in-depth surveys. The goal was to determine empirically what obstacles primary and secondary school early-leavers faced, what they achieved and what could be learned from their experiences. The project was funded by The UWI Trinidad and Tobago Research and Development Impact Fund, an initiative to support relevant research that addresses society’s pressing developmental challenges and can achieve a recognisable and sustainable impact in the short and medium term. “We trained about 100 persons to work with an in-depth survey instrument that they could use to conduct interviews within their own networks, turning communities into experts studying themselves,” says Dr. Kissoon. The collaborative aspect was crucial to the success of a project because of its scale. There were hiccups along the way, and all information had to be carefully combed through and monitored to make sure the proper process was followed. But even with what Dr. Mohammed calls “teething problems,” the data turnout was a resounding success. One of the more surprising and exciting aspects of the research was the expansiveness of the Geography Department’s data collection. This included spatial analysis that showed the different educational outcomes between urban and non-urban populations (although sometimes the outcomes were very similar). This is a fresh approach and an example of the benefits of multidisciplinary research. According to official national statistics, about 0.17% of primary-school children fail to sit their school-leaving exam every year compared with 1% of secondary-school children per year (about 1,000 students between Forms 1-5). Dr. Kissoon and her team wanted to find out more about these children: why they left, where they ended up, how to help them. The project extended throughout the country, with Kissoon herself venturing into prisons to get more information on the dropouts who ended up incarcerated. Despite the stereotypes of the “prison pipeline,” the national sample found that only 13% of participants had been in jail at some point. Discussions with those participants even yielded a trend of being more socially and financially stable than the general population of school dropouts, leading the team to question whether or not there was a correlation.

Among the study sample, there were a variety of influences on students that would eventually drop out of school. “The term ‘dropping out’ is kind of a misnomer,” says Dr. Mohammed. “Most of them are being pushed out, or they fall out.” Schools are often not equipped to give these students the extra attention they may need. Dr. Mohammed says that even though projects are being implemented by the Ministry of Education to give teachers the right tools, there are lots of issues limiting their effectiveness. “Ultimately, reforms in education away from exam-based assessment, investments in career guidance, psychological and social counselling in school and pedagogical training for academically qualified teachers are all essential,” says Dr. Kissoon. But even if the schools aren’t able to handle these special cases, dropouts often end up returning to complete some level of education or to get certification in some sort of trade. “Almost every person we spoke to understood the value of education,” says Dr. Mohammed. An overwhelming majority (88%) believed that education is a priority for their children. They acknowledge the constraints in the world of work without secondary school certification, the accomplishments of tertiary level studies, and the demands of advanced industrial, service, and creative sectors for educated employees and entrepreneurs. The next step for Dr. Kissoon and her team is the completion and release of a film to the public, giving some information on the project and showing the stories as told by the participants themselves. They will also publish a book of findings and the story of how the project was completed. Dr. Kissoon hopes that they can extend the study further to make a dent in “the pervasiveness of social inequality and the stigma associated with dropping out of school.” The team believes that this project has the potential to move the national conversation towards crafting a more inclusive education system that strengthens and supports those at risk of dropping out, so that one day we can close the cracks these students fall through. Results of this study are available online http:/sta.uwi.edu/rdifund/projects/schooldropouts/. This website hosts minutes, downloadable material, presentations, maps and statistics. Amy Li Baksh is a writer, historian and visual artist. She is currently working for the UWI Campus Museums Committee and is deeply invested in activism centred on the environment, marginalised social groups and animal rights. |