|

August 2009

Issue Home >>

|

This State of Independence: Poor mental health a major factor in society’s

breakdown

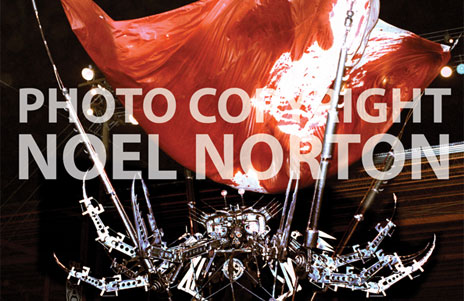

Man Crab, the Peter Minshall king from his 1983 presentation, River, portended the dread aspects of the misuse of technology. The metallic costume, portrayed by Peter Samuel, arrived on the Carnival stage like a dread oracle, bearing a pristine white square of cloth that stunningly became drenched with scarlet, symbolic of the lifeblood that was being squeezed out of nature and humanity.

Forty-seven years after Independence, Trinidad and Tobago, locked in its bloody pincers, is gasping for air, and the national flag might well be more truly depicted by the Man Crab canopy.

“We are now living fully in the age of Man Crab,” says Minshall, as his grim prophecy has come to pass.

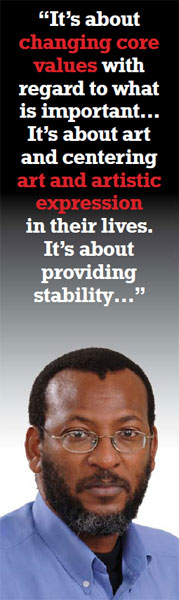

On the centrespread, psychiatrist Gerard Hutchinson offers a sociological perspective on why the society finds itself in this bloody mess.

This is not a fete in here

Poor mental health a major factor in society’s breakdown

By Vaneisa Baksh

July 1990 was indeed a coup because it introduced a gun culture to Trinidad that inside 20 years has so deeply embedded itself that no one knows how to reverse it.

Crime and violence have risen to such alarming levels that more people are migrating, travellers are being warned to avoid the islands, and murders have become daily fare. “We are now living fully in the age of Man Crab,” says Peter Minshall, and he had warned that it was coming 26 years ago. What has changed in Trinidad and Tobago since those heady days of Independence in 1962?

Echoing Rudder’s characterisations of a Trini mentality that imagines itself as “a chosen people” who “never worry ’bout these things” Gerard Hutchinson, a professor of psychiatry, believes that while recent factors contribute to the degeneration, Trinidad and Tobago was always predisposed to this journey

Prof Hutchinson, Head of the Department of Clinical Medical Sciences at The UWI, sees the pressure of a faster pace of life, which has contributed significantly to poorer mental health, the predilection for instant gratification, and the easy availability of drugs and guns, as the most recent dimensions contributing to the increase in crime and violence, but thinks that the elements for disorder were already encoded in the society’s DNA. Prof Hutchinson, Head of the Department of Clinical Medical Sciences at The UWI, sees the pressure of a faster pace of life, which has contributed significantly to poorer mental health, the predilection for instant gratification, and the easy availability of drugs and guns, as the most recent dimensions contributing to the increase in crime and violence, but thinks that the elements for disorder were already encoded in the society’s DNA.

More demands are being placed on people, requiring them to cope with more, and it is reflected in all the Caribbean islands, where the same kinds of patterns are emerging, “more lifestyle related diseases, more diabetes, more hypertension, more cardiovascular problems, more mental health problems,” he said. “It’s a challenge of development. It is related to increasing urbanisation and an increasing sense that it is through material things, structures, acquisitions, that you define your wellbeing, and that sets up a lot of additional pressure.”

Measuring accomplishments by their possessions has aligned the young to a culture of material gain by whatever means.

“They want to get the prize more quickly than people in previous generations because they think that the effort they expended to get to that point is in itself requiring of a reward, and they’re not necessarily prepared to work especially hard to achieve that and that has a trickle down effect. If you’re not able to climb the education ladder then you would still want to feel that you measure up and therefore crime becomes an attractive vehicle to achieve those things,” he said, and even free education does not compete with that.

Theorists, he said, say it’s not so much about rising from poverty; it’s more related to perceptions of inequality of distribution. If you can’t acquire it legally, you’ll resort to other means, or “be so stressed out by the fact that you can’t get it that you develop poor lifestyle habits that will make you sick.”

Trinidad has “particular things that apply,” he said, “and that is the whole drug culture,” particularly cocaine, that has “engulfed” us.

The gangs that dominate the criminal landscape are not a new phenomenon, he said, though their features may have altered because of drugs and guns. “It’s probably more widespread now, but that whole defence of turf and territory was a major part of all the steel band wars,” and this is a Trinidadian trait.

The steelbands represented communities “who had defined their territory and determined who should have permission to enter and what kinds of punishment they should receive if they violated those unwritten rules. It evolved into something that is defined now by more restricted terms and conditions, by predominantly illegal activity, and the range of punishment now begins and ends with use of a gun, rather than in the past, using bottles and knives and cutlasses,” he said.

“Many of the community leaders, as they were called, were also seen within their communities as benefactors in sports and entertainment, providing opportunities for people in the community, particularly younger people, and there is a sense that it is through this identification with organisations like that that many young people, particularly in the urban areas get their sense of belonging because they don’t get it anywhere else.”

Worsening violence is an issue, he concedes, but is “a symptom of something deeper, which is the quintessential Caribbean problem. It’s about identity and belonging,” and the loss of it, he said. “If you don’t feel like you belong somewhere then there’s no incentive to hold it together.” At the hospitals, the number of people seeking attention for violence-related issues has increased, even in psychiatry, but the institutional response to crime from the policing, judicial and health systems has “lagged behind,” he said. “We have not adjusted our capacity in terms of the demands that trauma for example, would be making on the system,” he said, “because of the trauma people react more excessively, more extremely to things that happen so they become so much attuned to risk that they would come to the hospitals almost at the drop of a hat.” The threshold for seeking help has dropped because people are so edgy, and it is “putting a lot of pressure” on the systems.

The violent ones share this hopelessness.

“The perpetrators of the violence feel that they are caught up in something that they can’t control. They feel that they are reacting rather than acting and I think that for the most part they would like a way out, but that way out has to be provided with dignity and pride, because one of the other things that has happened—going back to the whole material thing—is that peer respect or community respect or rank, has become a much bigger thing than it was.”

From his counselling work with prisoners and others, Prof Hutchinson finds that they “underplay their acts” and “don’t acknowledge a lot of what they do.” Some do partly because they don’t want to “create an impression of being a terrible, society-destroying person, which is interesting.”

“I think a lot of them could be reached if we had systems and structures in place to reach them, it is not that they don’t care but they have been taught or conditioned not to care. Once they’re taken out of that environment, they become concerned again about the things that most people in society are. They would say things like I really didn’t

mean to do that but I had no choice, or, it just turned out that way because...”

Violence that seems gratuitous or particularly savage might be influenced by the drug trade’s codes, he said. Another issue is the justification for doing it, which “is the result of a warped sense of humanness,” the inability to “recognise another human being as someone who does not deserve to suffer, which introduces the mental health component, because one of the things that makes us human is the capacity to recognise in another human being the shared responsibility for not doing harm or not deliberately trying to damage the process of their life, whether physically or otherwise.”

Something has changed in that inability to recognise that, wrought over time by repeated exposure to direct and indirect brutality.

The lack of consequences is another major factor, he said, “the belief that you can act and do these inhumane things with relative impunity. An illustration of that brutality is the whole murder/suicide thing which has been going on in Trinidad for a long time, and which is something that we don’t really see in many other places. It is that refusal, usually related to relationships, to acknowledge another person’s right to exist in a way that’s independent of whatever control you’re trying to place on them, but acknowledgement thereafter of the loss of or lack of value for life. It becomes almost inevitable that you would take your own life afterwards.”

In psychiatry, he said, some disorders have become much more prevalent. One of them is Borderline Personality Disorder; another is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In the first, patients have strong fears of abandonment and resort to shifting identity based on superficial acts, like how they dress, to be different. It suggests shallowness and instability, he said, similar to the traits exhibited by ADHD, which he thinks Trinidadians are so predisposed to on account of their overactive, impulsive and inattentive natures, that it has skewed the capacity to determine what is pathological.

The society itself presents an unstable framework because of its sheer complexity—if it were a patient, it would be diagnosed with ADHD—and its innate qualities combined with the drugs and guns met at a point of convergence that has erupted out of control, said Prof Hutchinson.

“I think the whole regional project is in danger.”

PROF HUTCHINSON’S TRINIDAD

- Young people expect things faster, not just in terms of crime, but in terms of the rewards they feel are due to them because they have achieved a particular level of certification.

- Social norms in Trinidad have always been very fluid, and flouting them has never been something that the society really creates a great objection to.

- We have a kind of sneaking admiration for the smart-man. We enjoy that capacity to beat the odds, to be publicly extravagant in terms of things we would say and what you would promise, and having a kind of personality that is hard to pin down, and which is unpredictable. I think we enjoy that.

- Trinidadians love intrigue and the more intrigue there is, even though it might be impacting them negatively, they enjoy it, they enjoy not knowing how things are going to turn out, and speculating on how they should.

- It’s become a cliché: our lawlessness, our flouting of norms and the rule of law.

- That whole existential thing is also a big part of Trinidad, that transience, we tend to shift from things very quickly… common references to seven-day wonders and people spending lots of money on costumes and throwing them away afterwards. I think we dwell in that world of transience.

- We’re naturally a little overactive, impulsive, inattentive…naturally, or innately maybe

A CASE IN POINT

“I saw a young guy once who was set adrift, didn’t really have any anchor, family was away… and he saw this guy who was reputed to be a hit-man in the community and the guy lived very well, lived much better than everybody else and he decided this was the way to live better. So he said, ‘I want to do that,’ and he became this guy’s apprentice, and this guy told him that to ascend to full-fledged status he had to demonstrate that he could kill somebody for no reason. Just for the single purpose of killing. So they went and selected somebody who was a watchman in Chancellor Hill, at some construction site, and he said well that’s your target.

Fortunately for him, or perhaps unfortunately, after he did it he was overwhelmed by remorse, and he said it wasn’t worth it and it led to such torment in his head that he gave himself in and ended up being referred for psychiatric help; but for whatever reason he had that capacity to step back after having done it. “

RECOVERING A LOST GENERATION

“Any recovery project obviously would have to be multi-focused. The top would have to reconstruct at the same time that the bottom is being reconstructed. If the top remains the same, any reconstruction at the bottom will collapse as well. The institutions necessary to facilitate that reconstruction have to be remoulded—specifically talking about education and health—and the boundaries set by authority figures in the society would also have to be reconfigured.

You hear all this talk about parenting, but that won’t work if the systems in which these people have to function remain the same. They have to occur in parallel. It’s about rebuilding, and a lot of stuff that’s been said a hundred times and more, about rebuilding communities and so on, but it’s about rebuilding them with a shift in terms of what is the purpose of their rebuilding. It’s about changing core values with regard to what is important, how quickly what is important is supposed to be achieved. It’s about art and centering art and artistic expression in their lives. It’s about providing stability which I think is a big influence on its own, the absence of stability in their lives and the absence of a stable care-giver whoever or wherever that might come from.”

|