|

|

|

|

August 2013

|

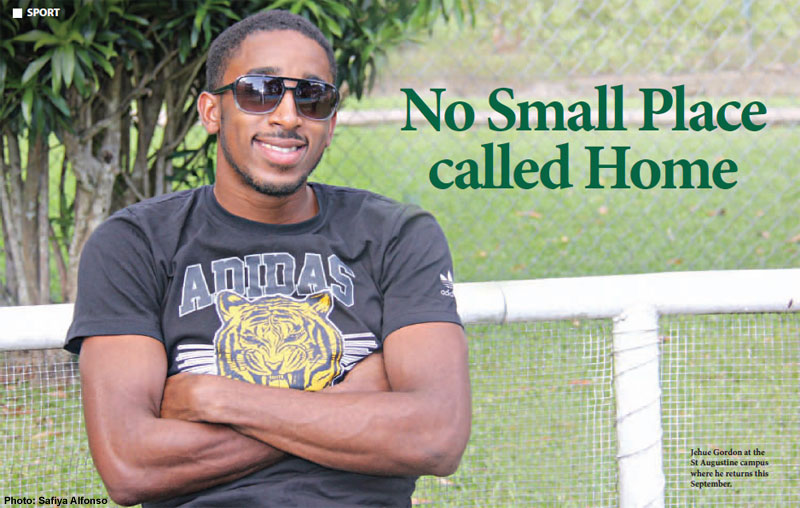

By Vaneisa Baksh It has been just a couple of hours since Jehue Gordon arrived in London from Moscow to overnight at a hotel before heading to his aunt’s before taking off to Italy for two races in the first week of September. Might seem a hectic schedule, but he’s grown used to it after four years. We’re talking by phone because there’s no internet. He has a bit of a cold, he says, so his voice is a little raspy. I tell him his comments on winning the gold medal at Luzhniki Stadium – about doing it local – were striking and had touched a chord in the country. What influenced his decisions to stay local? “The support from my family,” he says immediately, “… being able to stay in my comfort zone. Caribbean culture is so different from American culture. In Trinidad your parents do everything for you. My mum basically does everything, she cooks, cleans, washes…I just had to concentrate on training.” For Jehue, it was not simply about having people do things for him. It was recognising by watching the example of Marcella, his mother, and her hard work and dedication to his success, that he understood that it didn’t matter the size of the space you grew up in (money is not everything is a common phrase in his lexicon); it mattered how large you set your goals. He was never one to think small, and perhaps this is what caught the eyes of the other enormous pillars of support his life has had since he was 12: coaches and mentors, Dr Ian Hypolite, a psychiatrist and the almost 73-year-old 400m Olympian Edwin Skinner. Jehue is very clear that he was fortunate to have steadfast support from what he calls his close circle: Marcella, Ian and Edwin, who have stuck with him through thick and thin, and who have acted as inspiration, guides and protectors from the vagaries of a world that has not always been kind. Since winning the gold medal in the 400m hurdles at the IAAF world Championships on August 15, he has been interviewed countless times and he has consistently showered praises on these three, crediting them with providing him with the physical, mental and spiritual sustenance he has needed for his journey so far. It rings true, all of it; nothing shallow about this young man, who is able to identify exactly what he means when he talks about its significance to his upbringing and outlook and his capacity to focus and be disciplined enough to achieve his personal goals. Mind you, Jehue was not simply a wheelbarrow to be rolled along; from very small he had a keenly competitive mind and a fierce desire to excel. “I hate people to feel they’re better than me,” he says, as he defends his choice to stay at home to prepare for the world, in the face of many criticisms that he would be better off with foreign fare. “Everything I do, I do to the best of my ability.” His belief that everything we need to do well can be found right here in the Caribbean was not just inculcated by the three pillars, but embedded because of the deep trust he feels towards them. He describes their relationships and how he knows that “they didn’t do it for money.” “They encouraged me to further my education even when opportunities came for me to go professional,” he said, as he explains how “Doc” insisted that he would be better prepared if he nurtured his intellectual life just as fully. Three years ago he had enrolled in the Sport Management Programme at UWI, and when the semester reopens in September, he will be entering the fourth and final year. Even that choice had been questioned because he’d received offers of athletic scholarships from universities like Harvard, University of Florida, Mississippi State, Florida State and Texas A&M. “I wanted to show people I was not normal, that we can do things here. A lot of people limit themselves. They ask, why you want to study at UWI? Ask the CEOs of big companies here why they studied at UWI. I am 150% red, white and black!” So how has he been managing both his athletic career and his studies? “It has been tough,” he admits. “Success doesn’t come easily. It is hard work. But I don’t want people to feel I don’t work hard.” He says that he has had great support too from other classmates on the programme, who shared notes and had study group sessions to help him catch up. Given his mantra, he doesn’t ask more of the teachers, though he was really disappointed that one lecturer would not give him the one additional mark that would have made one of his papers an A. Still, he shrugs that off, and hopes that this upcoming year will be manageable now that most of his friends are finished with the three-year programme and are off-campus. He remains unwavering in his belief that Caribbean people should feel more confidence in their abilities. “I tried to get people to understand what I have been trying hard to do for all these years,” he says. “They didn’t see that.” It was a big hurdle for him to cross, and now with his gold medal to prove it can be done, Jehue’s message that when you think big, there is no such thing as a small place, might finally come across. |